Data is the key to understanding how we are doing at protecting our coastal waters. Thanks to the ongoing weekly water quality monitoring at our beaches, Save the Sound can review a deep dataset and build an understanding of water conditions and pollution sources and drivers.

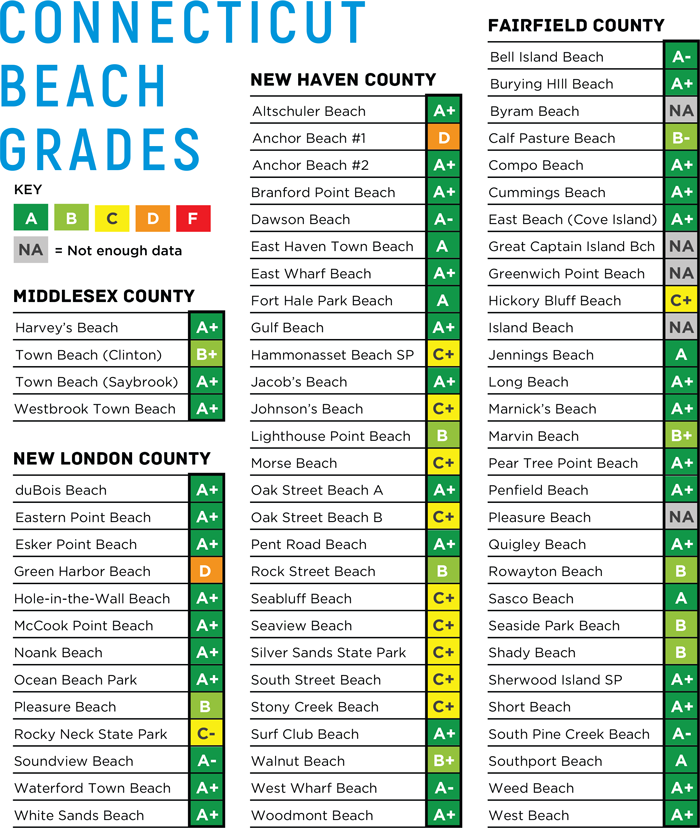

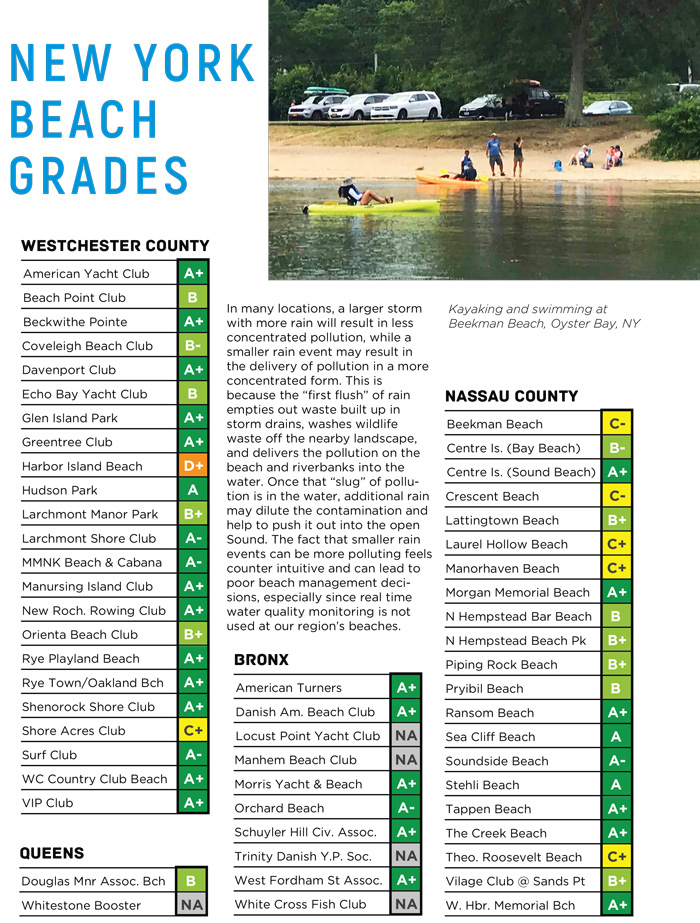

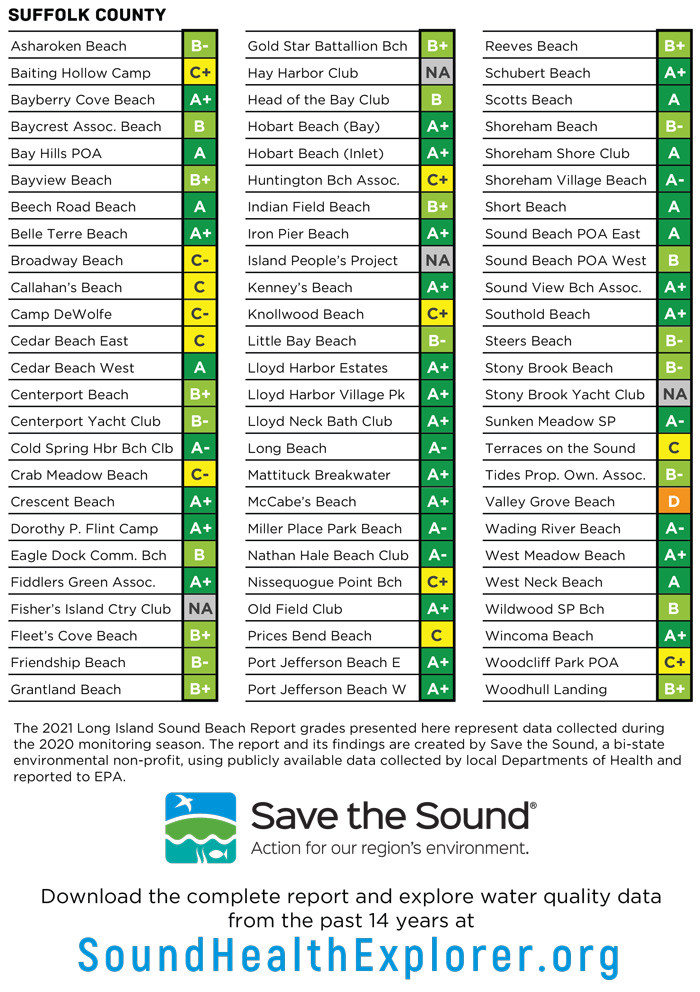

The biggest take-away from our beach data analysis is always how hyper local water pollution impacts are. The mapped grades show how beaches with “A” water quality can be situated within a mile or two of a beach with “C” or “D” water quality. Take for example Seaview Beach in West Haven, CT (“C+”) which is less than a mile from Dawson Beach (“A-”), or Crescent Beach (“C-”) and Morgan Memorial Beach (“A+”) both in Hempstead Harbor, NY. These illustrate how even within the same community you can have a pristine beach and one that suffers ongoing pollution, highlighting the role of the local community in protecting or restoring coastal water quality. If you have recurring high fecal bacteria levels at your beach that is not waste flowing in from another community, it is coming from your coastal watershed. We know this because when fecal bacteria reach coastal waters, they become diluted and dispersed by tides and disinfected by exposure to the sun’s UV rays, so they don’t generally persist long enough to travel very far from the source in open water.

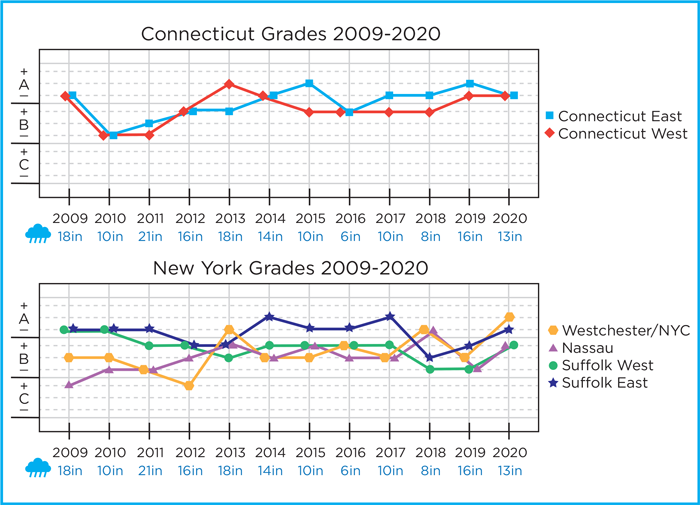

While some individual beaches consistently have excellent water quality, there is no one region that consistently earned the highest grade every year (Figure 1). Regional beach quality varies by year and all regions have opportunities for improvement. One driver for the variation is how each region is impacted by wet or dry weather, reflecting the differing sources of local water pollution such as the condition or type of wastewater infrastructure and/or the quality of stormwater management.

FIGURE 1. These charts show the annual regional beach grades calculated by averaging all the beach grades in each region that year. All data were collected by local Departments of Health and reported to EPA.

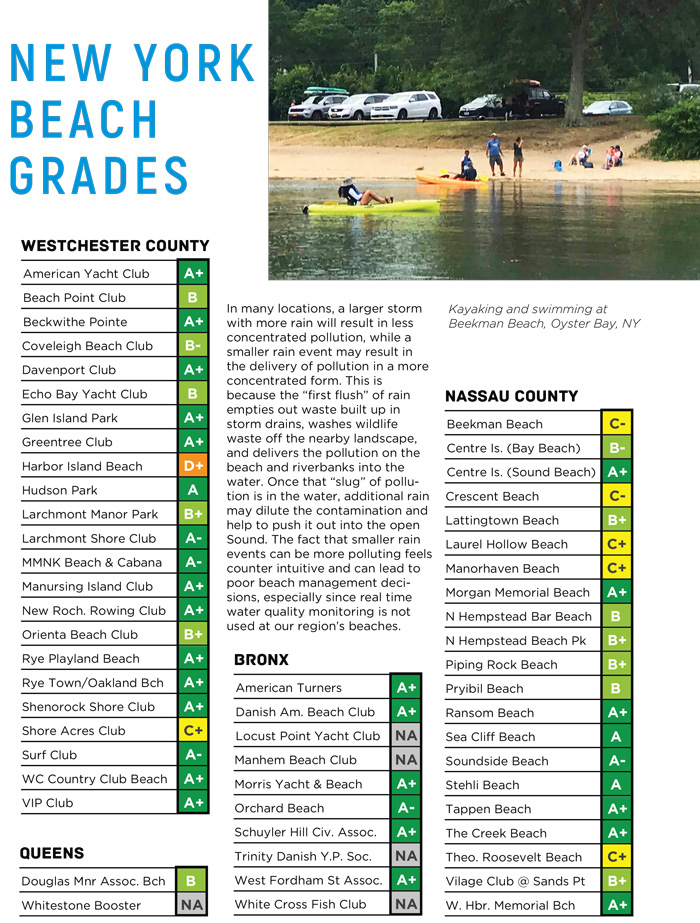

When it rains, bacteria—and pollutant-laden stormwater flows into local streams, rivers, and eventually into our coastal waters—often causing nearby beaches to experience a decline in water quality. In some locations, stormwater drainage pipes discharge directly to a beach, or to an adjacent area of the coast. How long it takes for a given beach to again be clean enough for swimming varies by location and by the amount of rainfall. The variables that determine the speed of recovery include the pollution levels in the streams and stormwater, the volume of water, and how well the beach water flushes with the open Sound. Beaches located inside a bay, where the tidal flushing is moderate, usually will take a longer time to recover from a storm than a beach on the open coastline.