New York City’s boating history comes alive at the City Island Nautical Museum

Located in a former school built at 190 Fordham Street in 1897, the City Island Nautical Museum has a gallery in every classroom.

In late June, I took a trip down a personal nautical memory lane. My cousin Peter Taylor, a talented marine photographer, and I drove over the bridge, first built in 1874, from the Bronx mainland and crept down City Island Avenue, the island’s main north-south artery. We were looking for the City Island Nautical Museum at 190 Fordham Street because we have family history there.

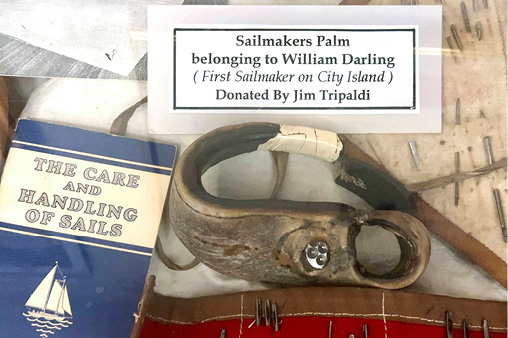

My great grandfather, William Darling, lived on this 230-acre island (about two-thirds the size of Central Park) in the late 19th century. The display case in the museum’s so-called Nautical Room has his sail sewing palm and a written sign noting: “William Darling – First sailmaker in City Island.” William Darling had nine children there including another William, who was my father’s father. The mythology of this surprisingly remote island in what is now the far reaches of New York City always loomed large in my watery imagination. Boats, sails, equipment, marine craft; the museum’s contents evoke the maritime past of the city that grew to the largest on the continent, with boats and sails giving way to ships and engines.

This is a pocket-size museum, on this site since 1964 and telling the story of the hub of NYC’s maritime history beginning in the mid-19th century. Local volunteers have long served as curators and exhibit designers; the vibe is primary school show-and-tell. But clearly the CINM has received loving care and financial backing to assemble exhibits befitting one of the greet maritime cities of the world.

City Island history in 200 words or less

City Island’s history dates back to the original inhabitants, the Lenapes, who fished and gathered clams and oysters here. In 1654, Thomas Pell bought the island along with over 50,000 additional acres on the mainland. It was an English settlement by 1685, when the Dutch had deferred to the English. A Pell descendent, Benjamin Palmer, changed the name of the island from Minneford or Mulberry Island to New City Island and attempted to develop a seaport to rival New York Harbor.

This tool kit was owned and used by the author’s great grandfather, William Darling,

During the 1800s, oystering was the principal industry. Because it was situated to service schooners travelling between New York and points north and south, the island was the base for Hell Gate

pilots boarding ships to guide them down the East River (Hell Gate is the current-ridden intersection of the East and Harlem Rivers). When oystering faltered, City Island reinvented itself as a major Gilded Age shipbuilding and yachting center.

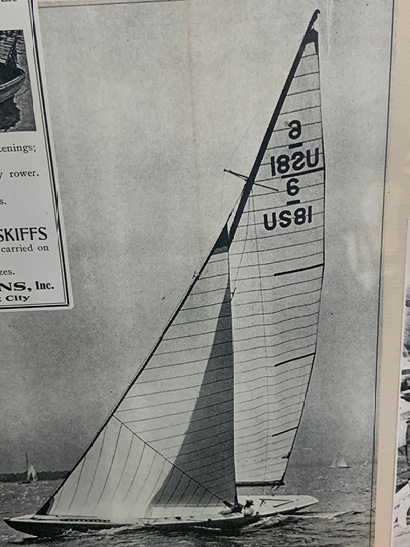

Two world wars brought in construction of military vessels for the U.S. government. When that cycle was finished, there arose the building of a series of 12 Metre sloops that successfully defended the America’s Cup, from Columbia (1958) to Freedom (1980).

Today, the island is a hodgepodge of marinas, yacht clubs, fishing boats, and the omnipresent neon-lit waterside restaurant. It could be mistaken for Coney Island but for the maritime heritage peeking out here and there.

Shipwrights at work in the rear lot at Minneford Yacht Yard, with Henry B. Nevins’ yard in the background.

Darling and Taylor rediscover their past

Cousin Peter Taylor and I had two successive brothers as grandfathers. Peter grew up sailing in Cold Spring Harbor and Oyster Bay, where today he’s the unofficial photographer of the Oakcliff Sailing programs. His match racing images in particular are featured on Oakcliff’s website.

Schools make good museums.

Reviewing a museum is a very personal exercise. Everyone sees what they want to see. The volunteers explained the logic of the museum. First, it’s located in one of the island’s historic buildings. Public School 17 was built in 1897, two years after the island seceded from Westchester County and joined New York City. Continuing in use for students until 1975, the building became the museum in 1986. Each classroom is a gallery.

New exhibit: Sailmakers Room

We were proudly steered us first into what had been in, on our last visit in 2019, a dusty storage closet for prints and frames. We dove right in. Too new to appear in the brochure, the Sailmakers Room highlighted sailmaking brands, some known and others unknown to us. Sadly, the island’s last full-service sailmaker has left.

The room documents an industry that operates today much as it had since the first sailmakers moved onto the island. Sails evolved from those made for commercial boats, with heavy cotton cloth and massive stitching, to the modern advanced materials, computerized design and now automated manufacturing.

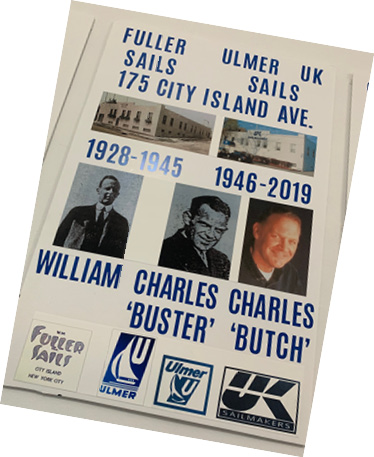

A succession of sailmakers fills this the smallest room of the museum: Ratsey, Ulmer, Hild and names that were new to us but had been major brands from the 19th century into the late 20th including Fuller and Vallentine.

We always thought our great grandfather had worked for Vallentine, but in one way or another it all started with Ratsey. How many Sunfish or Blue Jay skippers started sailing with their sails emblazoned with the company’s red half circle? Ratsey has the largest archive of materials in the exhibit, from the thick book of sketched sail designs to letters to the customer on the wall as well as client boats.

The Ratsey brand originated in England, as the official supplier of sails to the Royal Family. The original loft was on the Isle of Wight, as one would expect in the center of British yachting that saw in 1851 an upstart schooner named America beat the assembled British fleet.

The move to American waters, to City Island, came in 1902 when Ratsey & Lapthorn established a branch loft in the Jacobs Boatyard. In an interview in Mystic Seaport Museum’s archives, Colin Ratsey related that his father and grandfather were brought to the U.S. by “Mr. Vanderbilt and Mr. Morgan” because Ratsey were the only sailmakers with the Egyptian cotton they desired for their J-Boat sails.”

Sailmakers to the King

A Ratsey sales book for 1902-03 shows J. Pierpoint Morgan’s order for Corsair (his motor yacht), consisting of covers, mizzen staysail, straps and snaps of $765.50 that included delivery of $25. Farther on was noted $5,598.78 for Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Rainbow. She was one of the four NYYC 70-footer class built by Herreshoff in 1900. Thomas Ratsey boasted that the new building was “the largest private loft by far in the world; two floors, 175 by 50 feet, besides the basement…”

Photos of family members on the wall tell their stories. George, Ernest and Colin Ratsey carried the flag. Walls in this room and elsewhere show their sailmaking team at work. Ratsey kept in close contact with the new boat designers like Olin Stephens. In 1936, the $10,500 package cost for New York Yacht Club’s one-design class, aka the NY32, included a Ratsey main, working jib, genoa, and spinnaker.

Perhaps Olin Stephens’ best pre-war design, Goose was built at Nevins.

Like all growth businesses, Ratsey inevitably spawned spinoffs. The best known would become Ulmer, today known as UK Sailmakers Northeast, owned and operated off the island by Constantine Baris. Ulmer emerged as a group of sailmaking craftsmen dedicated to the emerging one design classes. My father’s Thistle #1079 had the blue-topped Ulmer designs. Charles “Butch” Ulmer’s recent induction into the Sailing Hall of Fame would be applauded by scores of big boat and one-design sailors.

Ulmer had a first mover advantage in the new class of downwind sails, the spinnaker. Owen Torrey, a professorial, analytical type, acquired his reputation as the master of the spinnaker. After graduating from the Naval Academy, Butch Ulmer dove into the business in 1960 and Ulmer grew on Long Island Sound and beyond. As ocean and inshore racing grew with the adoption of mass-produced fiberglass models, the demand for sails boomed.

There were other labels that came from the 19th century and grew, morphed and disappeared in the 20th century. You can trace them in binders that show the chronological order of development, and ads in magazines like Rudder and Yachting.

The binders carried the fascinating story of sails by Fuller over the years. They appeared to have the most aggressive marketing, and certainly the most fashion-forward advertising. Vallentine Sails had its origins in the work of a Scandinavian sailmaker who took space, hired cutters and sewers, and grew until competition increased and profits dwindled. Starting in the 1890s, Valentine with its red heart logo survived the war periods. Their ads show the one-design classes like Stars that were proliferating on Long Island Sound and beyond.

The Rosenfeld Room: the Main Hall and Gallery

We walked across the hall to the original room in the museum, which is lined with photographic essays, maps, models, and display cases This is a gallery of City Island’s best-known artisans, the Rosenfeld photo family. For three generations, starting with their boat Foto, a Rosenfeld searched up and down for that perfect print. Mystic Seaport Museum has the bulk of the portfolio, but some of the best work is right here. A selected group of the silvery, luminous prints that thrill all sailors covers the north wall. Witness Cotton Blossom and Bolero, the maxi boats of their days. They both are dwarfed by Herreshoff’s massive schooner Elenora.

What sailor’s home does not have a Rosenfeld coffee table book? The images are yachting portraits. Some of the most famous names have their place in the Rosenfeld portfolio: Bolero, Carina, Ondine. The Rosenfeld story is all about a multigenerational family with a unique artistic tradition. You can never forget a Rosenfeld, and you always remember where you first saw a given image.

The Walsh Library

Recently refurbished, the library features a collection of books along with binders and scrapbooks with topics from sailmakers to shorebirds. An impressive display of models sits atop the shelves. The most interesting feature is a database of all boats built on City Island since 1848.

The Nautical Room presents The Shipyards of New York

This is where, according to the sign, “you can explore City Island’s rich maritime history through historical photographs, memorabilia and artifacts The exhibit honors the shipyards, sail lofts, yachts and the people behind them… One of the unique features of the Room is the Oral History section which highlights life (in) the shipyards and sailmaking from former Ratsey employees… and a glimpse into the daily lives of the people who worked in the island’s shipyards.”

In its heyday, City Island had nineteen boatyards. A pamphlet on Long Island Sound boating struck a self-congratulatory tone:

“There is, perhaps, no place in this country better situated, or in possession of more advantages and facilities for yacht building, hauling out for repairs and storing for the winter than City Island. It is virtually the yachting center of New York. No yachtsman in this vicinity will dispute the fact that the Sound has superior advantages over any other place near New York City for yachting, which alone proves that someday City Island will be the great building place of these waters…”

Sailmakers love their logos.

One particular shipyard has always captured my imagination. Henry B Nevins is closest to my heart because my grandfather lived down the block. The nautical equivalent of a Formula 1 car constructor, Nevins built half of the eighty-three Six Metres built before World War II. That progression of Sixes, built from the early 1920s until the yard closed for good in 1954, were commissioned by Briggs Cunningham, Herman Whiton and others. The boat names are legendary: Djinn, Bobcat, Flirt; all of the designers preferred Nevins as builder. My personal favorite Six, Goose, a 1937 Olin Stephens design, shows up in a number of photos in the room. When Sparkman & Stephens designed the NY32 in 1936, it was Nevins that built twenty hulls (photos of the lofting are in a corner of the Nautical Room). Originally priced at $10,500, the NY32 has two thirds of the original fleet still sailing, a testimony to Nevins workmanship.

From Fuller Sails came father and son Buster and Butch Ulmer.

For many, it is Minneford that has name recognition. Why? The Americas’ Cup and the many defenders built there: Columbia, Constellation, Intrepid, and Freedom. The Minneford Yacht Yard was established on the beach between the Nevins yard to the north and the Robert Jacob yard to the south. Like neighboring Nevins and Jacob, Minneford built first quality custom yachts, but they also became dealers for productions boat builders. They “were among the first yards to include a private marina within the yard where existing owners could keep their yachts in a yacht club setting…”

Some of the lesser-known names were building the biggest yachts. The poster for Henry Piepgras Shipyard, City Island, Westchester, advertised “Construction in Wood, Steel and Composite.” The poster features photos, then taken with a glass plate camera, of the sloops, Titania, Tomahawk, and Katrina, and two-masted schooners Constellation, Quickstep, and Lasca. By eye, each craft is well over 70 feet. Gilded Age owners could afford it.

A.B. Wood was an example of a large yacht building enterprise that specialized in the designs of famed naval architects including William Gardner and England’s William Fife. The Wood Yacht Yard was in operation from 1860 until closing in 1930. It did not get as much recognition but, in its advertising, was “well versed in building in wood, steel or composite” and became innovative builders along the way. Photos of Syce, a 100-foot Gardner design, and Kestrel, a racing-oriented Fife design, demonstrate that among the dozen and a half City Island yards, A.B. Wood could build some very big yachts.

Other yards built motor yachts and commercial vessels. The walls are full of photos of patrol boats and minesweepers. All of this ended by or shortly after World War II. Today, one shipyard name remains. Minneford’s innovative approach to housing their customer, the marina, kept it afloat.

A mainstay of Mystic Seaport Museum’s sail training programs, Brilliant was an early collaboration between Sparkman & Stephens and Nevins. Courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum

Today, the proliferation of neon signed seafood palaces and a hodgepodge of housing covers over the past grandeur and intense maritime activity that charactered City Island through WWII into the age of one-design yachting.

The City Island Nautical Museum is located at 190 Fordham Street, Bronx, NY 20464. The phone is 718-885-0008. Find them at cityislandmuseum.org, and visit from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Hours are limited. (We came between 1 and 4 pm on a Saturday; i.e. weekend afternoons). Plan to dedicate at least two hours. I could’ve easily spent four if I’d listened to the oral histories. ■

Not a formally trained historian nevertheless a boat storyteller, collecting and reciting stories for the boating curious, Tom Darling hosts Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.