By Tom Darling

Imagine, if you would, if there were a television game show called “Herreshoff Jeopardy.” You know, the one where you begin your answer with “What is…?”

Here, the category is “American Daysailers of the 20th Century.” The game goes like this:

“The category is Herreshoff daysailing boats. For $100, this 26-footer was launched in 1913 and sailed for a dozen years, spawning numerous offshoots such as the Newport 29, the Buzzards Bay 25, and ultimately the S Boat.”

Buzzer. Hmmm…next.

“For $300, this graceful daysailer was a famous designer and builders’ personal boat, which he took to Bermuda in the off-seasons, and which served as his lunchroom in Bristol, RI during the years before, during and after the First World War.”

Cue the buzzer.

“And finally, for $500 (and our winner), this is the only Nathanael Greene Herreshoff design whose critical designer “Brown Book” is mysteriously missing from the 13,000-item Herreshoff archives in Boston, creating a design mystery worthy of Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie which remains unsolved.”

Clock ticks as the contestant mulls the answer.

Buzzer: “What is Alerion III ?” “Correct!”

Alerion is a boatload of stories, from the 1912 launching of NG Herreshoff’s (henceforth referred to as “NGH”) personal boat to 2020’s relaunch of Alerion Boats and its Alerion-derived designs. Let’s get to the history of the design:

Alerion III: NGH’s Favorite Child

The Alerion is a design born in local Bristol, RI waters from a succession of daysailing designs done during the Golden Age of the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company’s relentless design and construction campaigns of massive America’s Cup yachts at its complex stretching east-west down narrow Burnside Street.

The Alerion logo itself is an oversized image of a mythical bird, a cross between an osprey and a gull, in black or red. Its cachet as NGH’s personal boat and its sturdy combination of sea kindly hull and surprisingly stiff shoal draft has led to new interpretations of the design. There have been at least four generations of Alerions built and sailed on American waters. When we say Alerion in this article, we mean Alerion III (or “A III,”) HMCo. Design #718, the personal boat that Capt. Nat sailed, often solo, from 1913 to 1924, when he was well into his 70s.

Personally, I never set foot in Alerion III. She was on her way to Mystic Seaport Museum’s small boat collection when I first came to Bristol as a junior sailor with my Blue Jay from Long Island Sound. My own boat had been built by aerospace engineers with features Capt. Nat would have appreciated: bright finished transom, wood mast, high tech floorboards. But early on, I did sail in one of A III’s descendants, the Twelve-and-a-Half, the most plentiful of NGH’s designs and the parent of the fiberglass Bullseye and Doughdish models seen throughout the Northeast.

In the family of Herreshoff daysailers, the 12 ½ (rigged gaff or Marconi) was Alerion’s little brother. In the late 1960s at the Bristol Yacht Club, the 12 ½ was the hot competitive class. As a preteen with long arms, I got to crew on this 1920s-style wooden boat, gaff-rigged with its club-footed jib and a handkerchief non-poled spinnaker I always seemed to wrestle with.

Go forward more than thirty years to 1998. Moving on after a sailing career of performance boats from Thistles to Lasers to E Scows and back to Thistles with the so-called “Westport Mafia,” I settled into keelboat middle age in Nantucket. That experience came in the new Nantucket fleet of Chris Hood-built International One Designs derived from the Norwegian builder of the original wood versions commissioned by Larchmont Yacht Club sailors in the mid-1930s.

In 1999, I migrated with my young family from summers in Westport, CT to summers in Nantucket. This was where my New York City grandmother had gone before World War I, and where my ancestor, John Darling, had come from Martha’s Vineyard to go to sea when the family land gave out in Gay Head in the 1760s.

Today, most visitors arrive in Nantucket by ferry…at least those with two small children and a trunk full of American Girl dolls and beach toys. The drill is load your car on the ferry, then snooze for a couple hours on a hard plastic Steamship Authority seat. When you return to your car, you peek out through the portholes on the starboard side, looking for a glimpse of Nantucket Town with its church steeples over weathered grey

buildings.

Looking out that rusty porthole as we rounded Brant Point, I saw it: a handsome knockabout, royal blue, riding at anchor, her mahogany brightwork blinding in the midsummer sun. It was love at first sight. Riding nearby was a pale grey boat that resembled the royal blue one. The blue boat was and is A 2, Serendipity, owned by Harry Rein, the original captain of the Nantucket fleet. The grey boat was Owl, owned then by Eric Holch, a well known Nantucket graphic artist whose cards are a staple of Nantucket tourists and whose neckties are popular at what we used to call, pre-pandemic, “cocktail parties.” These two boats represent the historical record of this, the largest concentration of Alerions in the world.

When they raise sails, every boat’s mainsail has an “A” for Alerion, a dash, and a number. Hull #2 started construction in 1977. The latest, #32, was finished fall of 2019. The number on a boat’s sail gives you an idea of her vintage. It’s forty-one years back to the building of A 2.

Later that summer, my first sailing experience in an Alerion was less than auspicious. A DNF. Exactly how did that happen? I was a pick up off the dock on a windy, rainy nor’easterly day. The skipper’s wife had gone home and he needed a crew. We were charging upwind on starboard when our main topping lift, flying free, snagged the spreader of a dipping port tack boat and pulled the rig straight on top of me. Instantly, I was seeing stars from being clonked by a hundred pounds of splintered Sitka spruce. Not the omen I would have liked to start my Alerion experience with. But today, twenty-one years later, we find ourselves a part of the happy heritage of the Nantucket fleet, a group that will get full coverage in Part II of this piece.

Back to the Future of the Alerion Design

In Episode One of my “Conversations with Classic Boats”podcast (conversationswithclassicboats.com) on Dolphin, the 36-foot Newport 29, I had listeners send us the following questions:

Who was this Herreshoff character?

Where or how did he work?

What boats did he design and build via the Herreshoff Method?

What exactly is the Herreshoff Method?

All good questions that require a brief history of the Wizard of Bristol

Nathanael Greene Herreshoff, one of MIT’s earliest students (Class of 1870), was trained as a mechanical engineer and a self-taught yacht designer and builder who for more than sixty years from the late 1800s to the 1930s exerted more influence on marine design and engineering than any other figure. His legendary design genius, engineering innovations and manufacturing efficiencies led to the production of six America’s Cup winners and hundreds of other highly regarded vessels (Alerion was #718), the introduction of modern catamarans, the first torpedo boats for the U.S. Navy, and the first steam powered fishing boats in the U.S.

Running through May 1, 2021 at the newly redone MIT Museum at Sullivan Square on the north bank of the Charles River in Cambridge, MA is an exhibition called “Lighter, Stronger, Faster: The Herreshoff Legacy.” We were fortunate to have prior research done by wooden boat sages like Maynard Bray at Off Center Harbor and builders like Eric Fingers of Nantucket to guide us through Alerion history. We relied in particular on two pieces of historical reporting including 1) excerpts from Maynard Bray’s beautiful book AIDA, published in 2012; and 2) an article in the September/October 1997 edition of WoodenBoat

Magazine. We refer to both here as “AIDA” and “WoodenBoat” in parentheses.

Alerion III: Design for the modern daysailer

Keel-centerboard daysailers were derivations of New England “knockabouts,” a generously rigged, low-freeboard designs not conducive to keeping the crew dry. The Herreshoff customer was partial to a bit more comfort. Short overhangs and hollow bows were the design features that led to a boat throwing the characteristic southern New England chop aside. Alerion was a quantum leap in that regard. But the innovation came by way of NGH’s sharp eye observing native craft during his winter trips to Bermuda. Those beautiful hollow sections up forward are what so many of us consider as Herreshoff signatures, along with the round porthole and the rectangular coachroof.

In their book Herreshoff of Bristol, Maynard Bray and Carlton Pinheieo noted, “Alerion and her successors were remarkable in their short but graceful overhangs, high bows and low sterns with a beautiful sheerline connecting them, and generous beam on deck…”

Narrow at the waterline with a ballasted keel and centerboard arrangement, the easily driven hull shape culminated forward in distinctive hollow waterlines carried well up into her topsides. Built by the select crew in the Small Boat Shop at the Bristol yard, Alerion was, in Bray’s words, “one of Herreshoff’s most exquisite creations.” That distinctive bow, as we noted in past articles about her bigger cousin, the Newport 29 (windcheckmagazine.com/article/dolphin-and-mischief-mischief-the-herreshoff-twins-and-their-rogue-cousin/), was thought to come from one of Bermuda’s fitted sailing dinghies named Contest (AIDA).

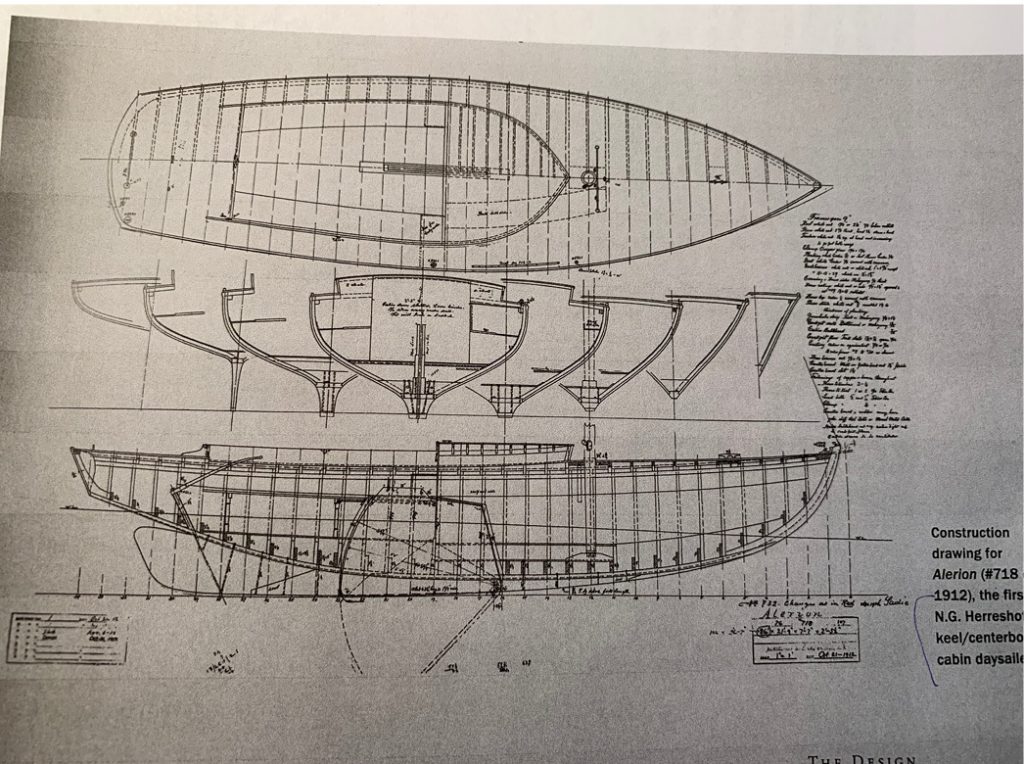

Yachtsmen appreciated this hull shape, in naval architect’s terms “especially the combination of a full forward deck line and a reversing load waterline that produce Alerion’s lovely hollow bows.”(AIDA). These 1912 construction drawings for Design #718 do not do justice to that exquisite turn of bow – the “Herreshoff Sheer,” as I call it. In a word, pretty, pretty, pretty.

What is this Herreshoff Method?

One hears from design historians and classic boat builders about the unique way Herreshoff Manufacturing built boats. The headquarters was on Burnside Street south of the downtown area of Bristol, today known best in New England for the red, white and blue center line on its main street and its big 4th of July parade.

NGH’s approach to design and building was meticulous and relentlessly documented. Famous entrepreneurs from other industries studied how NGH produced so many high quality boats in so little time, including steam, sail, and America’s Cup giants. But the NGH Method revolved around a couple of core principles:

1. Design from the half model. If you came to Burnside Street, chances were good you’d find NGH whittling a hull shape from a large piece of wood. The Herreshoff Marine Museum and the MIT Museum hold the collection of these models. Once faired, that model was measured with a contraption of his design that looks like to my eye like a large metal spider. That yielded the measurements of the various stations, the so-called offsets, the numbers at each frame…think of them as a fashion designer’s dress making patterns. From that, the factory made custom shaped frames which, with the hull upside down, took the individually-shaped planks. In wooden boat building circles, that was and is known as the Herreshoff Method.

2. Fully integrated manufacturing. Herreshoff built every component of each boat. Everything was made in Bristol, down to the screws and even the sails, which were made of custom-specified cotton sailcloth.

Alerion was built in the small boat section on Burnside Street, in between the major build programs for the America’s Cup yachts Reliance and Resolute. Capt. Nat had Alerion III shipped to Bermuda soon after her launching in 1913 for his winter trips to the island. He then returned home to Bristol in 1920, sailing her for a dozen years before retiring for good to Coconut Grove in Florida in 1924 with a more livable Alerion derivative called Pleasure.

It was in those post-World War I years that an older Nat Herreshoff found time to take his daily lunch, hop on Alerion III waiting at the dock, and singlehand her around Bristol Harbor. A relaxing lunch later, he had solved a thorny problem or two in that polymath mind, and he hopped off his gunter-rigged favorite and went back to work

This all changed when NGH stepped back into retirement in 1924. The Twenties were roaring, but business was slow. He held on to Alerion until September 1928 (WoodenBoat) when he sold her to his friend Charles Rockwell. At 79, NGH felt he had to give up sailing alone.

Meanwhile, it was time for Pleasure, the next, more liveable version of Alerion III. This boat was Nat’s equivalent of the post-retirement RV. It was designed to either go down the Intracoastal Waterway or be put on a train. Pleasure was built in only a few weeks in fall 1924 (the yard was short of work at the time), and shipped by rail to Key West and launched January 24, 1925. Captain Nat’s Alerion days on the water were past, but the design moved forward in new incarnations.

The post-WWI era was also the time of yacht clubs commissioning their own one-design keelboat fleets. Commodore Benedict of the Seawanhaka Corinthian YC had immediately ordered a duplicate of Alerion which he named Sadie, and then a few years later arranged for a fleet of smaller and less expensive Fish Class sloops with similar bows to be built for other members of the club. Likewise, Robert Emmons of the Beverly YC had become enamored of this same bow shape and commission NGH to employ it for a fleet of scaled-down Fish Boats that went on to be branded as the Herreshoff 12 ½, of which HMM turned out almost 400 over the next thirty years.”(AIDA).

In past articles, we have told the story of the Newport 29. The other similarly-sized variation on the Alerion theme, the Buzzards Bay 25, was his father’s favorite model, said son Sidney H. Counting all the designs related to Alerion, close to 500 of Alerion III’s progeny have hit the water. The proliferation of designs that evolved from this hull “indicates that for Nathanael Herreshoff the creation of Alerion was truly inspirational.”(WoodenBoat).

Great artists and craftsmen always carry secrets with them. At least two mysteries existed, in at least my own mind, before I did my work on Alerion. One case below I solved and one remains.

Mystery #1 for Alerion fans: What is it about that Alerion III color?

After Dolphin, Alerion was the first boat I wanted to interview for Conversations with Classic Boats. Dolphin is white, originally with the signature Herreshoff mid-green bottom…pretty straightforward as a color scheme. In the Small Boat Shed at Mystic Seaport Museum, the restored Alerion III gleams in her restored glory since her reinstallation in the early 1970s. Her light green topsides are jewel-like. On the water, the color changes with the light and the water conditions. What is that color?

When we were involved in repainting a boat for my Nantucket skipper, Brian Simmons, I told the story of when I last saw Alerion III in the water, on the end of the dock in the middle of the HMM waterfront in 1963. My father had taken over running the Pearson boatbuilding facilities in the HMM space on Burnside Street after Grumman took over the Pearson cousins’ business.

I swear that I saw a boat of the same color. Looking online, I traced the color path to of all places, the Smithsonian. There in the Smithsonian archives, along with other NGH artifacts, was the record of that color: Seafoam Green. So over the next winter, Brian’s First Tracks got the same treatment as Alerion III: Seafoam Green topsides, black boottop, white bottom. First Tracks is the southeasterly most Alerion in the anchorage, closest for the ferry passengers to admire and photograph.

Alerion III gleams in the shed at Mystic Seaport Museum.

Mystery #2: The Case of the Missing Offsets

When Eric Fingers, who today builds and services the Nantucket Alerion Fleet, consulted on the recent MIT Museum exhibit on the Wizard, he found something quite odd. There were no Alerion plans. All the MIT Museum had were two sheets of line drawings – none of the so-called offsets, the dress patterns of a boat builder, nor any specifications, be it for hardware, ballast for a keel, or a thousand other details. Where were they?

For every one of over 1,000 designs, NGH kept the vital statistics of each boat in a brown covered notebook (similar to a Moleskine). This contained all the specifications, including the measurements and the all-important offsets, essentially the measurements for the patterns for the frames over which go the planks. But Design #718 has no book…

First Tracks on her mooring in Nantucket

Our primary source article (WoodenBoat) tells the following story: In 1964, the fifth owner of A III, Ike Merrimen, donated her to Mystic Seaport. Standard procedure for a donation to the museum’s cavernous boat warehouse (across from the main Seaport grounds) was documentation of a boat’s sail, deck, construction and lines plans. This was done by naval architect Edson Schock in 1966, and a complete refit of A III was done under the supervision of Maynard Bray.

When in the early 1980s a family was looking for a boat for Buzzards Bay sailing, the search for the then well-worn plans turned up less than expected. Where was The Book? Where should we look? Where would a marine archeologist start their search? This is a mystery that we throw out there for the classic boat community to ponder.

In our August issue, author Tom Darling looks at the descendants of Alerion III, such as this Alerion 33 from Alerion Yachts.

Meanwhile, the boat building team at Mystic Seaport Museum’s DuPont Shipyard under Warren Barker built Curlew, the subject of the 1997 WoodenBoat article, which launched in 1994. The article’s photo layout shows the construction process from scratch, from milling logs to setting ballast. A Maine sailor had commissioned a replica called appropriately, Phoenix, launched in 1985. All of this was done with the authentic measurements, but not by The Book.

Previously in 1977, when another aspiring builder, Alfie Sanford and his assistant looked for the offsets, they were equally stumped. They came up with their own new set of plans that reflected underbody changes they made for Nantucket’s shoal waters. Did NGH lose The Book? Did he deliberately hide it so no one who came after him would have the recipe to build an Alerion IV? The Case of the Missing Offsets remains open.

In Part II of this story (in the August issue), we visit the largest flock of Alerions in the world, the one that floats in Nantucket Harbor. Since 1979, that fleet, identical to Alerion III above the waterline, has become the most competitive on the island. ■

Tom Darling organizes Team Dolphin for its annual Opera House Cup sail, and sails Alerions in Nantucket Harbor. He has written articles on Reliance and Dolphin, among other Herreshoff classics. You’ll find Tom’s excellent podcast, Conversations with Classic Boats, at conversationswithclassicboats.com.