By Roger Vaughan

Editor’s note: Cutting a wide swath through the male-dominated sports of auto and ocean racing in the 1960s and ‘70s, Patsy Kenedy Bolling acted like one of the boys and was accepted, making lifelong friends with drivers like Sir Stirling Moss and Dan Gurney as well as countless sailors, perhaps most notably one R. E. Turner III. In the words of author Roger Vaughan, she “would challenge you, beat you, drink you under the table, and make you want to call her the next day.”

How well Patsy integrated herself on Eagle can be measured by the trick owner Ted Turner and his crew played on her as they approached Mamaroneck, New York, the site of the late Bob Derecktor’s northern boatyard. In a world of rough customers on the hard side of yachting, Bob Derecktor stood out. Legend had it Derecktor ate nails for lunch and tossed at least one customer a week out of his yard for having the gall to inquire about the progress of his million-dollar boat Bob was building.

How well Patsy integrated herself on Eagle can be measured by the trick owner Ted Turner and his crew played on her as they approached Mamaroneck, New York, the site of the late Bob Derecktor’s northern boatyard. In a world of rough customers on the hard side of yachting, Bob Derecktor stood out. Legend had it Derecktor ate nails for lunch and tossed at least one customer a week out of his yard for having the gall to inquire about the progress of his million-dollar boat Bob was building.

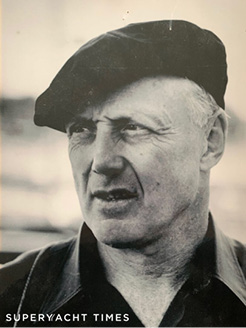

Derecktor had built his first boat as a teenager. He dug a hole in his family’s yard and got his father to help him pour a lead keel. A tireless worker from the old school with a keen mind and skilled hands, Bob began his day by rowing four miles to work in a fast pulling boat he’d designed and built. He dressed the part, with a wool cap pulled over his large head and red-white-and-blue suspenders stretched over his barrel chest. He usually had a chip balanced on one shoulder. Patience was a foreign object for Bob as he stormed around his yard every day running a one-man show involving the direction of several boats under construction, designing and fabricating hardware, managing purchasing, and taking twelve minutes for lunch.

Turner, who’d enjoyed many an amusing, pitched go-round with Derecktor, thought it would be fun to send the unwitting Patsy in to see Bob when they arrived, bearing a bunch of caustic messages that were guaranteed to piss him off. “Ted prepped me to meet him,” she says. “I got dressed for the role, wearing my red hat and suspenders. Ted said to give Bob a rasher of shit, like how come there was no one to greet us and help us tie up when we arrived, what kind of sorry-ass operation are you running here, and where’s our mail?—barge in and kick ass.

“I walked in and said to Rosie, his secretary, I wanted to see Bob. She said, Who are you, he’s busy. I made a fuss. He comes out of his office and says, Who are you? I say, Who are you, because I had no idea. And he says, I’m Bob Derecktor. And I said, Oh, I’m Patsy Kenedy and I’ve been sent here to ask why no one was out there to take our lines, and I ranted on, snapping my suspenders. He’s leaning up against the doorjamb cheekily smiling and shuffling papers in his hands and I’m going on about what a lax scene it is, and he says, Well, fine, how do you do, and we’re not a marina, you know, we’re boatbuilders, and he went into a huff. I put out my hand and said, Ted put me up to this. You’re a good guy and let’s get on with it.”

Irascible boat builder Bob Derecktor Courtesy Derecktor Shipyards

They became tight friends, Patsy and Bob. Eagle was in the yard for a month. When Eagle wasn’t racing locally, on weekends, David Andre and Patsy would race on Salty Goose (fifty-six feet LOA), the fourth boat Derecktor had built for himself, one that would win her class in the 1975 SORC. Patsy soon realized Derecktor was cut from the same rugged cloth as her father. “Bob was so gruff, so tough. He’d kick guys in the ass. Why are two guys carrying this plank? Gimme that, I can do it myself. He was uncompromising. Both my father and Bob did whatever they needed to do to get it done. They didn’t give a shit about the law.” The difference was that Bob Derecktor didn’t shoot anyone, not that we know.

Jim Mattingly worked for Derecktor for fourteen years. He has a good laugh when he recalls Patsy showing up dressed like his boss. “Patsy got along with Bob, with men in general,” Mattingly says, “because she wasn’t afraid to do anything. She did whatever was asked of her. And she was a good listener. That made her a welcome part of any team. And it made her a great learner. You didn’t have to explain things to Patsy twice. She’d figure it out. And she never contradicted anyone. She just took it all in, evaluated it, and made a decision.”

Patsy remembers being in the yard one Sunday and hearing hammer blows echoing in the quiet of the big shed. She followed the sound and found Bob having a parental visit with his two daughters, ages six and eight. He was teaching them to drive and extract nails. “He was only slightly embarrassed,” Patsy says. “He just shrugged and said, It’s a good thing for them to learn to do, isn’t it?”

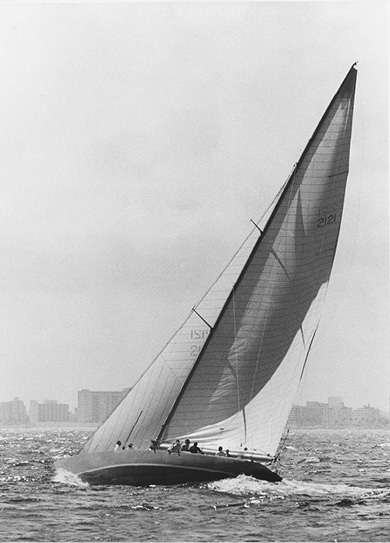

American Eagle charges upwind. The Patsy Bolling Collection

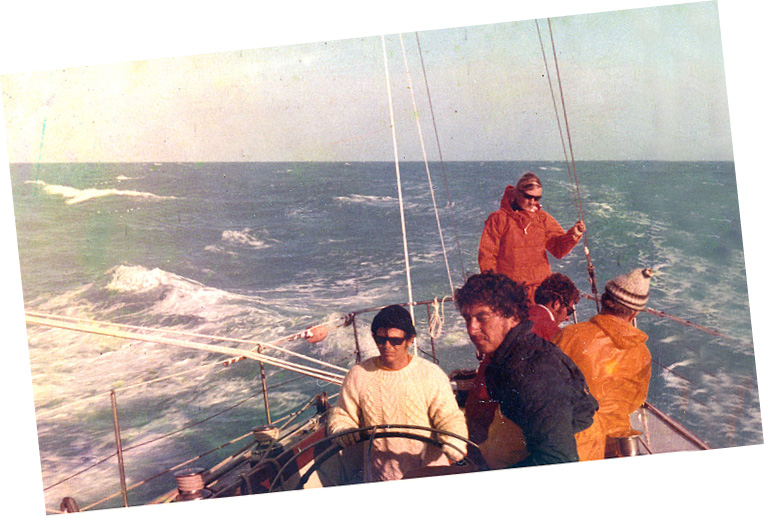

Patsy was confirmed as a crew on Eagle for the 1969 transatlantic race from Newport to Cork, Ireland. Her assignment was handling the running backstays and other jobs in the back of the boat, leaving the big coffee grinder winches to the strong guys. Although when it was necessary, she could turn those handles. Giving her the backstays was testament to the degree of confidence Turner and Andre had in Patsy’s ability. Eagle had a permanent backstay hitched to the masthead. The “runners” attached to the mast three-quarters of the way up. They were secured to the deck near the rail on each side of the boat, aft of the wheel, with a multipart wire rig that led through a block on the deck to a large winch. The runners were essential for altering sail shape via mast bend, and for mast stability. “They were a very important item for this boat,” Patsy says today. “That mast looked like a wet noodle at times.”

During tacks and jibes, easing the old runner as the boom passed amidships and securing the new runner before the new tack was fully established required perfect timing and fast hands. Several hard turns with a winch handle—in low gear—would fine-tune the tension between ten thousand and twenty-thousand pounds. Fail to get the new runner up on time, and in the right sequence, and the mast could go over the side.

The transatlantic race was one of five required races to be completed over a three-year period for boats competing in the initial World Ocean Racing Championship. Since Turner had bought the boat in 1969, American Eagle had been in the thick of it. The race turned out to be mostly uneventful, although halfway across the Atlantic the bolt that passed through the mast below the spreaders to hold the lower shrouds in place broke. The port upper shroud, a rod, went snaking down to the deck and bounced overboard. The spinnaker was up at the time, pulling the mast forward and putting pressure on both lower shrouds, which angle slightly aft. Fortunately, the wind speed was under twelve knots, and the sea state was reasonable.

Patsy on Eagle’s afterdeck during the La Rochelle Race, 1969 The Patsy Bolling Collection

“Ted was on deck ordering lines to be rigged to take the strain off the mast,” Patsy says. The spinnaker was struck to ease the forward pressure. Both backstays were quickly tensioned. “A guy named Jim Brass was hauled up to make a diagnosis,” Patsy says. “The hole in the mast was now egg-shaped, elongated from the bolt working against the mast. Trying to pass a bolt through the mast once the starboard shroud was connected was a bitch. To do the job Jim needed a one-inch bolt ten inches long, threaded at both ends. We scrambled through the boat to find something that would work. Lordy, we found two one-inch pieces. And we had a spare lower rod. Using the longer piece we were able to make the repair in two hours, with lots of rags and sealant used to cover the oversized hole in the mast. We got a jib up in the meantime, so we only lost a couple knots of boat speed.”

The fact that Turner and his crew had decided to take a boat designed as a daysailer to race around buoys into the ocean was risky business. It’s lucky, as Patsy says, A. E. Luders built Eagle “like a brick shithouse.” A wooden boat, her frames were quite small, but they were on six-inch centers. There were scary moments. “We put the bow under to the mast several times,” Patsy says. “The tension, the vibration, was an eerie feeling. The load at the mast step had to be incredible. The boat had never seen anything like that. I bunked in the forepeak and it often felt like the bow was going to break off. I told the guys if it does, grab my feet and pull me out.”

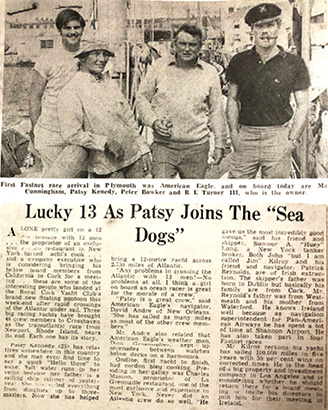

American Eagle was the first boat to arrive in Plymouth after the Fastnet Race. From left to right are Mac Cunningham, Patsy, Peter Bowker and Ted Turner. The Patsy Bolling Collection

Eagle would win her class in the race, and take third overall, keeping her well in the hunt for the WORC crown. But to Turner’s annoyance, it was Patsy the Irish press was interested in. Under the headline “Patsy joins the Sea Dogs,” the story in the Cork Examiner read: “A lone pretty girl on a twelve-day passage with thirteen men . . . landed at the Royal Cork Yacht Club’s brand new floating pontoon this weekend after rapid crossing of the Atlantic under sail . . . Any problems crossing the Atlantic with thirteen men? we asked her. ‘No problems at all,’ she said. ‘I think a girl on an ocean racer is great for the morale of the crew.’”

“Patsy is a great crew,” said American Eagle’s navigator, David Andre, of New Orleans. “She has sailed as many miles as most of the other crew members.” A picture of Patsy at Eagle’s helm ran with the story. ■

PATSY is available from Amazon books…and is highly reccomended!

Roger Vaughan lives, works, and sails on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.