How not to lose your love of sailing

By L. South Fulweiler

As a child growing up in the Ocean State, I’ve been sailing almost all my life. Many things have come from my long days on the water, including friendships, memories, ungodly sunburns, and unforgettable life lessons. But sometimes the awe factor of sailing fades, and I’m here to say it shouldn’t— not when the sunsets are like fire, the stars like magic, and when each sailing experience can change you for the better.

Alongside Geronimo prior to departure

I know about this because most recently, I crewed aboard St. George’s School’s 70-foot Ted Hood-designed cutter named Geronimo on a transatlantic trip beginning in Bermuda and ending in Spain (with a stop in the Azores). This voyage changed my perspective in ways a trip around the New England coastline couldn’t. Spending over a month aboard a sailboat with nine other people, six of us students, three professional crew, and one captain, was absolutely life changing. I learned so much from the little things like watchkeeping, log entries and sun sights to bigger things like how people function as a collective and how to overcome seemingly impossible challenges. Maybe most importantly though, I regained a sense of wonder for sailing. It was this adventure where I relearned what sailing can be when you take away the daily distractions and man-made clutter. It was this adventure where I returned to what made sailing beautiful in the first place — strong winds, tossing waves, and a vast, open sky.

Bermuda with all its white roofs and neon colored water was the perfect starting point. As if in purposeful contrast to the setting, what met us before we broke ground was a day filled with strong winds (stronger wind than any of us expected), angry waves that caused our bow to hobby horse up and down incessantly, and pretty much universal seasickness (which somehow, probably by sheer force of will, I avoided). I squelched the thought that I wouldn’t see land for almost two weeks and tried my best to focus on the clouds and waves and occasional flying fish. I spent the hours on deck watching as the smudge that was Bermuda faded to nothing on the horizon.

We broke into our watches right after we left Bermuda— four hours on, eight off. Being on watch was sometimes painful and included handling the sails, taking the helm, cooking and other chores. I had the noon to 4:00 p.m. and midnight to 4:00 a.m. watches. While this was seemingly the most disruptive to my sleep schedule, it had insane benefits, my favorite perk being the stars. The distances between me and all that dotted light reminded me every night why I loved my time at sea; the freedom of all that space and time.

The author in Bermuda

Preparing for my watch and my time “driving,” I would come on deck in more layers than I thought possible and wait for my hour at the helm to come around while staring into the darkness with my eyes squeezed open to stop myself from dropping to sleep. Functioning at all from midnight to 4:00 a.m. on a boat is a struggle, particularly during an ocean passage. The little things I never considered a task became challenging when trying to do them aboard an ever-rocking, tossing, galloping sailboat. Even the basics like just getting dressed for my night watch were not easy. The only light allowed was a red one (white light destroys your night vision), and while it was fine for most things, trying to differentiate between pieces of clothing or see details became impossible. And then there were the twin forces of gravity and inertia working to careen me into someone else’s bunk, into a bulkhead, or onto the floor. Plus, I was always cold at night regardless of the reported temperature. My fellow crew would find me shivering and bundled on deck, sometimes wearing an embarrassing amount of clothing. Although this watch was often brutal, it made the afternoons under a hot, golden sun all the more beautiful.

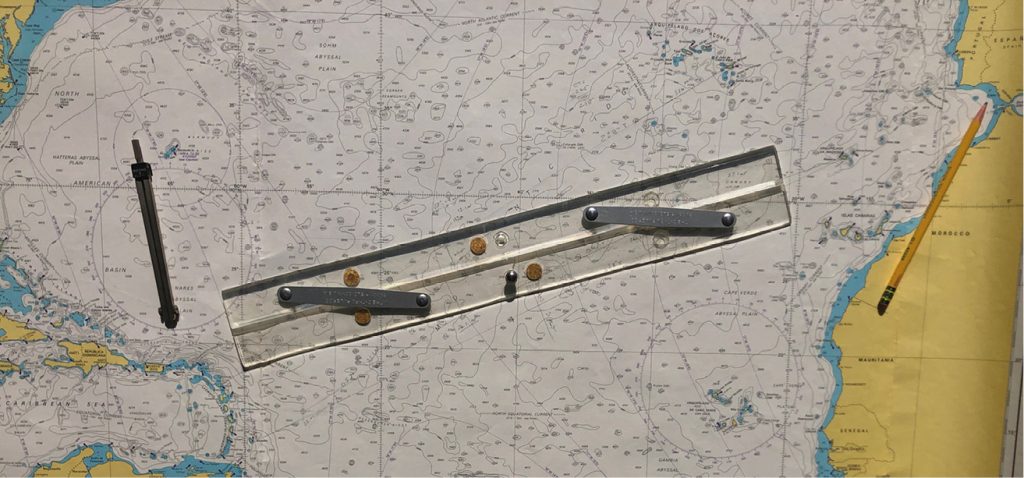

Charting a transatlantic crossing

At first the nighttime hours crawled by, and then I began noting what time it was based on how the sky looked. This was when I first started paying attention to the world around me, and when the magic of my experience began to take shape. My watch sometimes started out surprisingly light, with milky moonbeams illuminating the boat’s deck and making it possible to occasionally spot the glistening backs of dolphins as they played on our wake. As the hours marched on, the moon would gradually begin to set, getting larger and larger and turning from white and gray to yellow, orange and red. The moon’s triumphant burst of color before it rested for the day was simply incredible.

Sunrise, somewhere in the Atlantic

Then, darkness. Sometimes it was hard to see my own hands in front of me, and it looked as if we were sailing into nothingness, into the great abyss of space, but that made the star gazing so much better. I was amazed by how the stars twinkled. We’ve all heard the nursery rhymes about stars twinkling, but I didn’t know they actually do. Trillions of stars faded and flickered in and out of focus, some so bright you’d see them when you closed your eyes and some you had to squint to see at all. Some planets were there too, tinged red or green.

Arrival in Spain

During the day, I watched the waves chase each other, crashing and curling when it was windy. The days when we reefed our mainsail and jib were the days the waves were the most detailed, with tendrils of spray that wove and shuddered, and delicate traces of turquoise at the crest. When it was calm, the waves meandered, lazily rolling and reflective, as we motored through still air. There was general frustration toward the waves that ate at our hull because they sometimes came with more wind than we thought we needed while also making it nearly impossible for anyone to take a bucket shower on deck. The flat days could be maddening too, with a constant dance between motoring, sailing, motorsailing with just the jib or main, or both.

And just like that, we fell into a pattern, but not into normalcy. Days came and went, usually and thankfully uneventfully, but we still appreciated every one of them, every sunset and sunrise. We weren’t too far into the voyage before I saw the magic of sailing had taken hold of each of us. We didn’t have our phones or Netflix which are the oxygen of my generation, and having that constant, easy entertainment stripped away forced us all to look around. To really look closely; close enough to see the colors wrapped up in each wave, the patterns on sea turtles’ backs, and the shapes of the water splashed across the deck. The lack of an Internet connection forced everyone to talk to one another, and my hours on deck were always filled with laughter and chatter, sometimes meaningless, sometimes anything but. We discussed things as trivial as waffles versus pancakes, gossiped (a lot), and at times accidentally worked our way to more intelligent topics like the Mystery of Roanoke and the fate of an ever-expanding universe.

Living in close quarters meant we really got to know each other by the end of the voyage, and we’ll always share this unforgettable memory. Sailing brings people together. From small boats like double-handed dinghies to a vessel like Geronimo, sailing is like a social glue. Here, six teenagers stuck on a sailboat without our usual distractions ended up working together really well. The power of a group, a unit, a collective, glowed on this trip.

Celebrating a successful passage with snacks and smiles aboard Geronimo

I remembered wondering if I’d be able to see the stars like this when I got home to Jamestown, Rhode Island as if I’d just not been looking at the sky in the right way. But no, I can’t really see the stars like I did because the ambient light is too bright and tree canopy too dense. Still, I can see other things I’d never seen before, like how the fog looks as it travels over Narragansett Bay or how the rain pitters gracefully on the dock railing.

Sailing from Bermuda to Spain taught me there is never a reason to be bored when there is so much to see, there is nothing more powerful than a body of people climbing the same mountain, and any task, no matter how daunting, can be achieved if you grit your teeth, put on a few layers, and look up at the stars. But maybe most importantly, this voyage reminded me of how much I love being on the water.

I’m so appreciative of Geronimo’s professional captain and crew. I learned a ton, and I’m hugely thankful to St. George’s School for this opportunity. ■

A sophomore at St. George’s School, South Fulweiler can usually be found reading, drawing or spending time on the water with friends. Living in Jamestown, Rhode Island with her parents and black pug Anchor, South enjoys runs by the beach and getting ice cream after sailing. She loves to write and is an editor on her school paper. Her interest in journalism and language arts push her to always be creative and inquisitive.