By Richard du Moulin, Storm Trysail Club

For the past thirty years, leading sailing organizations have developed best practices to maneuver back to and attempt to recover a man overboard (MOB). The Storm Trysail video, “Safety-At-Sea: Man Overboard Recovery”(available on Facebook and YouTube), is probably the best video production of MOB practices, combining footage from on-the-boat, off-the-boat, drone, and a helmet-mounted GoPro camera worn by the MOB. In that video, various methods of approaching (returning to) and recovering (hoisting on deck) the MOB were demonstrated. However, recent fatalities and new practices make it an urgent priority to revisit approaching and recovering an MOB in more detail and introduce a few new ideas. Two major challenges to a successful outcome have become more apparent:

- The risk of the boat fatally striking the MOB during the approach and recovery, and

- The difficulty of lifting the MOB up on deck.

Getting back to the MOB safely

Using the engine is critical to enable the yacht to return to the MOB promptly and make the first approach successful. Too many documented MOB incidents have seen up to four approaches without the assistance of an engine, where the MOB is OK on the first failed attempt but ends up a fatality due to further exposure or being run over by the yacht. All crew should know how to start the engine.

The operating characteristics of modern, high performance yachts increase these difficulties. Their sailing speed results in greater separation from the MOB, particularly downwind. When trying to motor back to the MOB, these designs are often underpowered, displaying poor handling under both power and sail at low speed. Their light displacement and narrow, high aspect keels increase the risk of the bow falling off and striking the MOB. Narrow rudders and smaller propellers – often retractable and located far forward from the rudder – reduce steering control. Dual rudders do not line up with centerline propellers, eliminating the prop wash necessary to steer at slow speeds.

Even conventional displacement yachts – with more engine horsepower and easier steering at slow speed – can run down the MOB, especially at night in rough water. Know the steering characteristics of your boat, especially at slow speed.

If the yacht can operate well under power in the conditions, in addition to the spinnaker or jib, the mainsail should also be doused. If the main (or jib) is needed to assist the return to the MOB, the douse can be delayed.

When the MOB is spotted, the Lifesling is deployed and the yacht motors just fast enough to maintain good steerage – maybe 3-4 knots (test your own yacht) – and passes close (about 15 feet) to leeward of the MOB, turning sharply so the MOB can make contact with the Lifesling. The yacht then uses full power to stop dead in the water about two or three boat lengths away, but not dead upwind out of fear of drifting down onto the MOB.

The Mid-Line Lift as seen by the MOB: Note the halyard snapped to the Lifesling line (visible above the heads of the crew).

Recovering the MOB – A New Idea: the Mid-Line Lift

Regardless of whether the yacht is conventional or high octane, lifting the MOB safely on deck is difficult due to the freeboard and wave action. It is most dangerous on yachts with chines or hull flare where the MOB can slide under the hull. Using a Lifesling eliminates the need to make direct contact with the MOB. However, pulling the MOB immediately alongside can put the MOB in danger of injury.

Here’s a new idea: instead of the crew immediately pulling the MOB alongside, leave the Lifesling line cleated aft at the stern. Then, preparing for a Mid-Line Lift, walk a spinnaker halyard aft and clip it onto the Lifesling line, outside the lifelines. As the halyard is taken up, the halyard shackle slides out on the Lifesling line, and the MOB is pulled upwards (about half out of the water) and towards the yacht. As the MOB reaches the yacht, the MOB is lifted into the air to be grabbed by the crew. At no time is the MOB free-floating and vulnerable alongside the yacht.

Fitting out your yacht for the Mid-Line Lift

The Mid-Line Lift has a 1:2 mechanical disadvantage, but most yachts have winches and crew strong enough to recover the MOB. The initial hoisting that brings the MOB near the yacht is quite easy. The final ten feet gets more loaded as the MOB is lifted out of the water.

Double-handed sailors, whether racers or cruising couples, might be more challenged if the remaining crew on board is not strong, or if the winches are underpowered. If practice confirms this, the Mid-Line Lift might need to be replaced by a 1:1 setup where the MOB is pulled in to about 30 feet from the yacht, then the halyard is secured to a previously tied loop. While not as effective as the Mid-Line Lift, this setup reduces the time the MOB is floating alongside before being hoisted.

To properly size the Lifesling line for a Mid-Line Lift, it must be a few feet shorter than twice the height of the spinnaker halyard sheave off the water. Otherwise the 1:2 setup will cause the halyard to two-block as it reaches the masthead before the MOB is on deck. There’s no need to cut the Lifesling line. It can be cleated at a marked location and the remainder hanked up.

Replacing the yellow Lifesling line with 6mm floating spectra can add extra strength and resistance to sun and abrasion. No yellow Lifesling line has parted during our drills, but the Mid-Line Lift does create extra load.

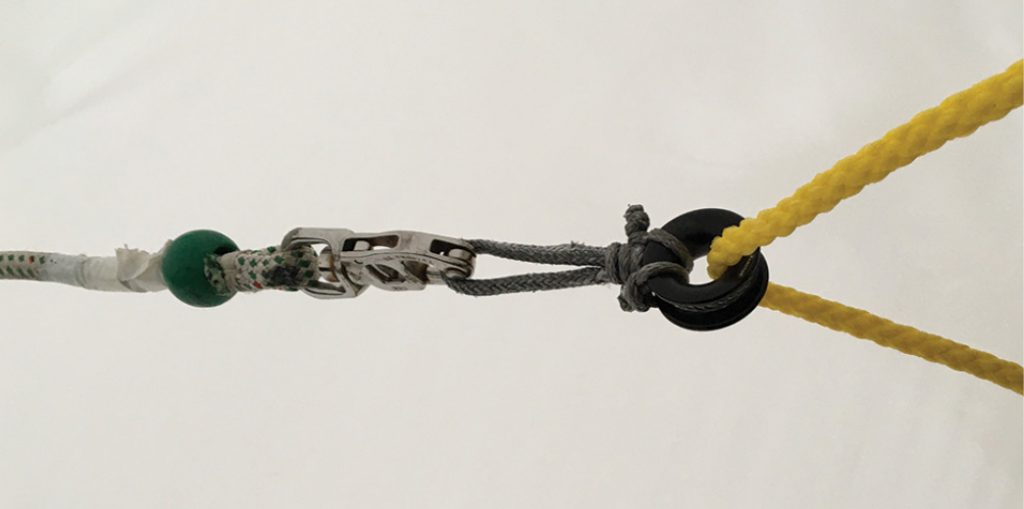

Spinnaker halyard snapped into sliding loop

Most halyard shackles slide easily along the line, but you can also fit a sliding loop with a short strop onto the line. Make sure to secure the loop with a quick release knot next to the end of the line at the stern cleat so it is easily available when needed. Also, check your spinnaker halyards to ensure they are long enough to reach the stern of the yacht to clip onto the line (or loop).

If the MOB is Incapacitated

When the MOB is unconscious, injured, hypothermic, or weak – and unable to grab the Lifesling – this is when the amateur crew is at a disadvantage. Many professional yachts have a trained Rescue Swimmer – connected to the boat with a safety line – who can reach the MOB and together get Mid-Line Lifted. Without a professionally trained Rescue Swimmer, the amateur yacht must maneuver much closer, adding some degree of risk, and lower a Rescue Crew on a halyard into the water to secure the MOB. This Rescue Crew is best equipped with a climbing harness, helmet and Rescue PFD. This style PFD is less cumbersome than an inflatable and has a safety ring on the back for a tether.Techniques to secure the MOB include using a tether, a second halyard, Lifesling, Galerider drogue, or even bear-hugging the MOB. To watch the crew of the 100-foot Comanche perform a Mid-line Lift with a Rescue Swimmer, go to ussailing.org/education/adult/safety-at-sea-courses/safety-at-sea-resources/#comanche.

In practices and real MOB situations, we find it is difficult to attach a halyard or tether to the D-rings of the PFD because the inflated chambers block the D-rings on most models. Some new PFDs have a dedicated lifting strap built into the unit. For the Clipper Race, Sir Robin Knox-Johnston fits permanent lifting straps to the webbing of the PFD. Make sure your PFD has an easily accessed lifting point.

Sir Robin Knox-Johnston demonstrates the lifting straps permanently attached to the webbing of his inflatable PFD.

Another useful tool for snagging an incapacitated MOB is a mooring hook (Wichard makes a good one) attached to a pole or boat hook.

Practice with your crew on your yacht

A yacht owner/skipper is the Responsible Party with traditional and legal responsibilities to plan for the safety of the yacht and crew. The Cruising Club of America just published an excellent one-page “Culture of Safety” statement (cruisingclub.org/article/safety-culture) that is worth reading. Customized MOB evolutions for your yacht and crew must be developed.

Serious practice is required to evaluate your yacht’s characteristics under sail and power, especially at slow speed and maintaining position. It is strongly recommended that before going offshore, a crew should practice about four hours of upwind and four hours of downwind recoveries using a tallboy buoy that is easy to pick up and doesn’t blow downwind like a cushion. Initial practice should be in medium breeze and then work up to heavy air and night. Try fitting an AIS or strobe to the tallboy.

Use Lifesling approaches to make contact with the “tallboy MOB” as if it were an MOB. Also try to maneuver alongside to test your yacht’s handling characteristics and improve your skills for picking up an incapacitated MOB.

At the mooring or dock, two hours of Mid-Line Lift and other recoveries should be practiced with a real MOB wearing an inflated PFD. With your Rescue Crew lowered on a halyard, test the various alternatives to recover an incapacitated MOB. Life Raft + Survival Equipment (lrse.com) sells a very useful Jacobs-style ladder that provides a good backup.

Finally, head for the bar and take with you two (yes, you should have two) throw bags and pair your crew up on the lawn for a “Throw Bag Duel at 20 Paces.” Great way to practice a backup method to get a line to an MOB!

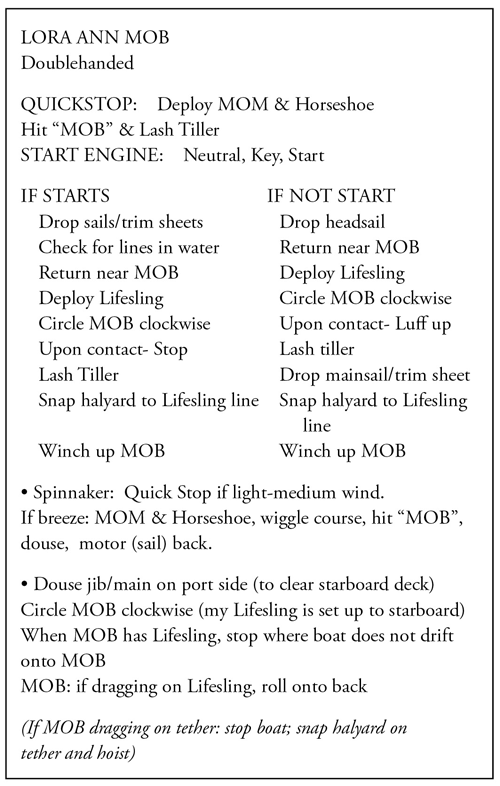

With all the crews’ input, an MOB Plan should be drafted and posted that reflects what works best for your yacht, and has been understood and practiced by your crew. If you’d like to share your MOB Plan with the Storm Trysail Club for posting on our new website, please email it to me at rdumoulin@intrepidshipping.com, Attention: Safety at Sea. Here’s the Doublehanded MOB Plan for my Express 37 Lora Ann:

What if you are the MOB?

During Storm Trysail MOB research, some of the best videos have been from the GoPro camera mounted on A helmet worn by the MOB. Our “volunteers” have also made interesting observations.

If the inflatable PFD doesn’t inflate automatically, remember to pull the manual inflation tab. Make sure you know where yours is located! You must know how to maintain and operate your PFD! If manual inflation fails, try the oral inflation tube – best done floating “comfortably on your back” (easier said than done). Better solution: Go back to step one and learn how to maintain your PFD!

Tighten your crotch straps to elevate your mouth above the water. Check that your strobe is functioning. Hold the AIS in the air for better transmission. If the water’s choppy, pull on the hood/face shield and face downwind.

Your whistle might be your most important communication asset. The piercing sound travels well and has saved many lives. When the yacht is in sight, splash your arms calmly to make it easier for the yacht to see you and know that you are mobile. When you make contact with the Lifesling and slide into it, roll over on your back if the yacht drags you too fast.

Dragging by a tether

We have to thank Sir Robin Knox-Johnston for a novel application of the Mid-Line Lift, which is standard procedure in his Clipper Around the World Race. Check that your halyard shackles are large enough to snap over your tethers. If not, clip a standby carabiner at the mast base.

There have been an increased number of incidents where tethered crew have fallen overboard and dragged alongside. This can be fatal. However, it is no excuse for not clipping in!

If sailing upwind or jib reaching, the helmsman must immediately luff up in order to slow down and reduce the pressure on the MOB. Luffing also reduces the heel and helps lift the MOB out of the water. An Upwind Quick-Stop leaving the jib aback works very well (once your hikers are off the rail).

Sailing downwind with a spinnaker, in light/medium wind the helmsman can do the Quick-Stop. In heavier wind, bearing off and collapsing the chute may be the safest option. You’ll know from your hours of MOB practice…right?

In any case, the Mid-Line Lift is the fastest and best method to recover the MOB. Immediately upon discovering a dragging MOB, the crew instantly snaps a halyard onto the MOB’s tether and hoists. The halyard lifts the MOB out of the water.

Prevention: To avoid the risk of being dragged, always use your short 3-foot tether when working on the leeward side of the boat, or double your 6-foot tether around the jackline and back to your D-ring. Then you cannot reach the water if you slip. Also use the short tether when changing headsails that can pull you overboard, or when waves can lift you off the foredeck.

Rig your jacklines as far inboard as possible, and if your yacht has a trunk cabin, run a second pair of jacklines along the cabin top parallel to the grab rail. All offshore tethers should have a release shackle on the inner end. If you are drowning on the tether, and your yacht is not responding, you might have to make the awful choice of pulling the shackle and becoming a full-on MOB. ν

Credits

Thanks for the very important inputs from: Stan Honey (Navigator, Comanche); Sally Honey (Chair, US Sailing Safety-at-Sea Committee); Chad Corning (Crew, Argo); Chuck Hawley; Dick York; Buttons Padin; Adam Loory; swimmer/MOB Gerard Girstl; Kelly Robinson; Jim Murphy and the crew of Inisharon; and Sir Robin Knox-Johnston.

Richard du Moulin has competed in four America’s Cup campaigns, a Transpacific Yacht Race, a Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race, three Rolex Fastnet Races, six Transatlantic Races, and twenty-five Newport Bermuda Races. In 2003, he and co-skipper Rich Wilson set a new record for the 15,000-mile passage from Hong Kong to New York City aboard the 53-foot trimaran Great American II, eclipsing the time set by the clipper ship Sea Witch in 1849. A member of the Cruising Club of America, Royal Ocean Racing Club, New York Yacht Club, and Storm Trysail Club (Past Commodore), he’s currently serving as Chair of the Storm Trysail Foundation. He lives in Larchmont, NY.