Exploring the Island Chains off Cartagena, Colombia

By Ruth Emblin

Modern Cartagena

In March of 2022 we finally set off on a trip that should have happened two years earlier. The anticipation had been building for a long time, as we had heard about the wild beauty of the island chains just off the coast of Cartagena, Colombia.

A colorful Cartagena balcony

Cartagena, or better, Cartagena de Indias, is a Spanish colonial city on the north Caribbean coast of Colombia. The old town remains enclosed by majestic walls with watchtowers and cannons and is worth a visit of at least two days to explore the silent witnesses to an eventful history. The colonial vibe that still permeates the old town is best experienced in one of the many boutique hotels occupying historical buildings. These hotels have preserved the character of the original buildings yet provide modern amenities for travelers. You feel completely immersed in history when you stroll down the streets.

Most buildings have been expertly restored and are adorned with balconies overflowing with tropical plants, such as bougainvillea, trumpet vines, and climbing lilies. Often the balconies in narrow alleys are covered in riotous displays of color from one side to the other. The next street over, you may find a building waiting to be brought back to life, stucco crumbling from the walls and doors barred. Yet another few steps will bring you to a small plaza teeming with life, street vendors hawking their wares, while families sit on benches enjoying sweets sold by a young man with a colorful cart. There is no sense of hurry despite the hustle and bustle, time seems to slow down within the ancient walls of the old town.

Cartagena was founded in 1533 by Pedro de Heredia, a Spanish Commander, who built a settlement on the site of an abandoned village. The first settlers to join him were sailors from the Spanish town of Cartagena, and they named the new town Cartagena de Indias in keeping with the Spanish colonial naming traditions.

The original tribes believed to have occupied the area since 4,000 BC were known as the Puerto Hormiga culture, later to be replaced by the Sinú society which settled along the Caribbean coast of Colombia. The Sinú endured for centuries until the colonization by Europeans almost completely wiped them out. The Sinú buried their dead in tombs all over the coastline, a fact that was discovered by the new inhabitants of Cartagena around 1552, when the town was devastated by a fire. Thanks to the Sinú tradition of burying their dead with precious burial objects, the settlers were able to rebuild Cartagena de Indias in stone, and the city began to prosper. Spanish treasure began to make its way through Cartagena, and the increasing fame of the city attracted many who sought to make their fortune in the New World.

In 1586, Sir Francis Drake led a successful attack on Cartagena, looted and burned many of its buildings, and demanded a substantial ransom before leaving. This prompted an expansion of the city’s fortifications, including the walls as well as a fort on a hill, later to become the Castle San Felipe.

Cartagena’s natural harbor had two entrances, which could have made defense more complicated, had nature not helped. Located on each side of the island called Tierra Bomba, the more commonly used channel was known as Bocagrande (“big mouth”), and was a wide, hard to defend entrance. The other, Bocachica (“small mouth”), was rarely used because it was narrow, and winds tended to be less favorable there. Over the years, sediment began to build up in the Bocagrande channel, and soon a strip of newly created land began to block access. This was advantageous for the defense of the city, as the smaller Bocachica entrance was easier to control, ships having to pass through single-file. The Castle San Fernando de Bocachica was built on one side, and the Fort of San Jose on the other side, creating a crossfire situation for any would-be invaders. In addition, a floating chain was suspended between the two forts.

In the late 1700s, the Bocagrande channel began to reopen due to shifting currents. The decision was made to build an underwater wall to keep Bocagrande permanently closed. It was a feat of engineering that endures to this day, and boats with a keel deeper than a couple of feet still are unable to pass through the entrance.

This cruise visited parts of the Caribbean unknown to most sailors.

Only a few decades later, Cartagena was at the heart of the war between Spain and Britain. The Battle of Cartagena in 1741 was a very bloody affair but ended in victory for the Spanish forces. San Felipe Castle, just outside the harbor, helped protect the city and continued to do so many times more against further incursion attempts. Soon after the battle, the city decided to add additional fortifications, making it the most protected port in South America.

Cartagena Old City Wall © Jesse Kraft

Cartagena attempted to gain independence from Spain in 1811 but failed. It took another decade for the city to finally cut ties with Spain during the War of Independence. Thanks to its strategic location in the Caribbean, Cartagena continued to flourish as an important trade port and attracted settlers and tradespeople alike. To this day, the city has a tangible vibe of history and progress all in one, and it is easy to imagine colonial life while strolling its streets and enjoying the multifaceted culture on display. Of course, the city has expanded tremendously since those times, and the more humble neighborhoods outside the ancient city walls, as well as modern districts like La Manga and Boca Grande, resemble many contemporary cities throughout the world.

If you are into culinary experiences, Cartagena will not disappoint. The typical dishes you should definitely try include arepa de huevo (a refried corn pocket filled with egg and spiced meat), ceviche (raw marinated fish), pargo frito (fried fish), arroz con coco (a staple – rice with coconut), pan de bono (special bread rolls), mote de queso (yam and cheese soup), cazuela de mariscos (seafood casserole), posta negra cartagenera (slow cooked pot roast immersed in a brown-sugar-like marinade), and more, and not to forget a flurry of delicious desserts with tropical fruit, dulce de leche, tres leches cake and so on.

After a couple days of enjoying Cartagena, we made our way to the commercial harbor in La Manga. Our charter boat was docked at the Club Nautico de Cartagena, a no-frills marina occupied by every type of vessel imaginable. We met our crew, hauled our luggage on board the 45-foot Dufour monohull, and went to a nearby supermarket to provision for a week’s sailing. My mouth watered when I saw the variety of tropical fruits available, and I probably went overboard with my purchases. Just for the record, I have not yet met a tropical fruit I didn’t like! We took two shopping carts’ worth of provisions back to the boat and settled in.

Our boat was rather tired-looking and presented quite a few challenges, but after establishing that the hull, rigging and engine were fine, we set off. We had hired a couple of locals, brothers Charlie and Kevin, to crew for us, as it is advisable to have someone on the boat at all times. Cartagena is a relatively safe city, but we were venturing into cruising grounds that do not see too many U.S. travelers. Having crew on board would also allow us to leave the boat and explore without having to worry that someone might be tempted to check out our vessel and its contents. Better safe than sorry has always been our motto.

Leaving the harbor, we got a firsthand look at the immense bay that was the object of so many battles and invasion attempts. Nowadays, the bay is fringed by a very large commercial port with many container ships that enter and exit through Bocachica one after the other. The water is brown thanks to the Canal de Dique, built by the Spanish in 1852, which connected the Magdalena River to the bay. The Magdalena carried vast amounts of sediment into the canal, which made it impassable. In the 20th century, attempts were made to open the canal again, but sedimentation remained too concentrated for ship traffic. It still carries sediments into the bay, changing the color significantly.

Our boat, Rush Slowly

We made our way to the channel leading to Bocachica, dodging commercial traffic and many small powerboats. We passed the two forts, San Fernando and San José, and finally emerged into stunningly blue Caribbean waters. As we raised our sails and plotted a course toward the peninsula of Barú, a multitude of flat-bottomed powerboats with flimsy canvas covers passed us on both sides, transporting daytrippers to the outlying islands. Many of these boats seemed overloaded with passengers, riding low in the water, yet at top speed. The sea state was not exactly calm, the wind kicking up, and these “lanchas” were bouncing across the waves like speed demons. I was quite happy to be on a slower sailboat rather than being tossed about in one of those small vessels. Despite Cartagena boasting an active sailing community, we did not see many other sailing vessels, mostly powerboats and commercial or Colombian Coast Guard ships passing us in either direction.

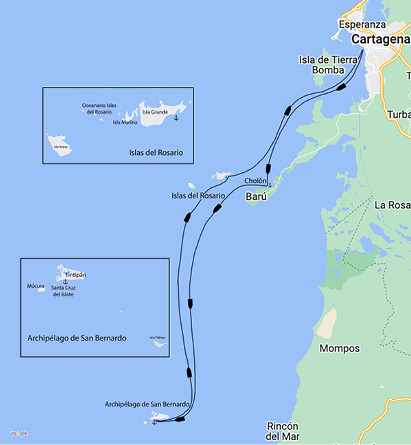

After a few hours of sailing south along the peninsula of Barú, we approached Cholón, a picturesque bay behind several small fringing islets, about 16 nautical miles from Cartagena. Technically, Cholón is considered part of the Islas del Rosario chain, even though it is still part of the peninsula. The entrance to the bay is very narrow, and coral heads and shifting sandbars make navigation for a deep-drafted sailing vessel a bit challenging. However, with a look-out on the bow and a close watch on the depth meter, we made it safely into the bay, passing an in-water bar on the beach of one of the small islets, busy with daytrippers enjoying tropical drinks and snacks while sitting on bar stools under palapas sunk into the sand. Loud music drifted across the bay, while powerboat captains revved the engines of their sleek crafts.

We opted to move past the party boats and found a quiet spot to anchor deeper in the large bay. There are several restaurants that cater to visitors, but as they were quite crowded on the weekend, we opted for take-out of fresh fish, langostinos, and octopus while enjoying the sunset from the cockpit of our boat. The prices in Cholón have two levels – local and outrageously expensive for tourists, which we, clearly unable to pass as locals, unfortunately had to deal with. Our first dinner cost more than all the dinners we purchased for the rest of the week. Knowing that there would be no more opportunities to find an ATM once we left the mainland, we were a little concerned, but the further away we moved from the peninsula, the more reasonable food prices became.

The next morning, we struck out towards the Archipélago de San Bernardo, a chain of islands about 30 nautical miles southwest of Cholón. The conditions were not favorable for sailing except at the start of the leg. The “iron genny” had to be deployed once we sailed past the Islas del Rosario, which we planned to visit on our return. One benefit of running the engine was that a pod of dolphins was attracted to our boat. I sat on the bow watching their joyful antics, breaching, jumping, racing each other and our boat, for a good twenty minutes until they all peeled off to pursue whatever other dolphin activities they all had planned.

We eventually made it to Tintipán, the largest island of the archipelago. Our crew knew of a mooring close to shore yet in deep enough water. When we approached the mooring, I was not overly confident as it looked quite neglected and was missing any eye or attachment point. Our crew assured us that the mooring was well looked after, and just looked a bit rough. Crossing our fingers, we lassoed the mooring ball and settled in for a couple of days.

Tintipán features several hotels and hostels, and its center is dominated by a large, picturesque lagoon bordered by dense mangroves. The island is part of the Parque Nacional Natural Islas Corales del Rosario y San Bernardo, one of Colombia’s national parks. One of the interesting aspects of Tintipán are hostels built on posts in the shallow water, aptly called Casas en el Aqua, houses in the water. Regrettably, hostel staff is generally not welcoming to cruisers. They are jealously guarding against access by anyone who is not a guest, even if you wish to purchase drinks or food. This seems to be the M.O. for most hotels and guesthouses on these islands. While all beaches in Colombia are theoretically public, hotel staff will turn anyone away from “their” beach if you are not a guest. Cruisers are undeniably a rarity here (we saw fewer than a handful of sailing vessels all week), and suspicion rules despite the potential benefits for these businesses.

After speaking to a few people, we felt that if more cruisers were to come to these islands the attitude might change. If you still want to visit a beach rather than just swim from your boat, there are public beaches on all islands, and the locals are very welcoming. It is an immersion into local life, which is also a great experience. After exploring Tintipán’s mangrove lagoon by dinghy, we headed to Múcura, a smaller island to the west of Tintipán. The waters were turquoise and crystal clear, and we enjoyed a swim at the Playa Touristica Isla Múcura. Múcura has a number of beachfront hotels and hostels, most of them built in the palapa style typical for the region, wooden buildings with tall, round roofs covered in straw.

To be continued… ■

Ruth Emblin is Vice Commodore of Duck Island Yacht Club, a Past Commodore of Essex Corinthian Yacht Club, and co-chair of the Gowrie Group CT River One-Design Regatta to benefit Sails Up 4 Cancer presented by Cooper Capital Specialty Salvage.