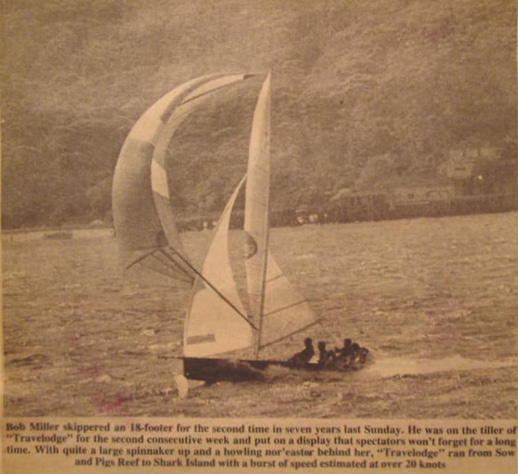

From The Cooper Archives: Travelodge, an 18-foot skiff skippered by Bob Miller, rips across Sydney Harbor in a “black nor’easter.”

Time once was when if you went to a sailboat race the organizers started the race. Unless there was no wind, or serious fog. If there was “too much” wind, great don’t start. Sadly, this is no more. The idea that it’s blowing too hard has had the threshold of what constitutes too hard gradually lowered. If the threshold windspeed, at which the organizers deem it too windy, continues to fall, perhaps we will all end up sailing Thumb Yachts.

I learned early on that if you did not sail in hard wind – 25-plus – in one’s Laser, and later in a Finn, in practice, you had no hope of sailing in such conditions in a race. The Laser group I regularly sailed with in the day would sail in 25-plus knots of black nor’easter, on Pittwater to the north of Sydney and out into Broken Bay, no problem. I once sailed a Finn Nationals in Melbourne, Port Phillip Bay, a body of water perhaps 25 x 25 miles large and exposed to the SW. The regatta went for a week, back in those palmy, far distant times of “one race a day.” For three days it blew 30 out of the SW, which at the regatta site was onshore. Twenty-five or so Finn sailors negotiating their way off the beach and out through a 4- to 5-foot sea was an entertaining exercise in seamanship. No one batted an eye at the conditions, as far as I can remember. Ched Proctor, prominent since then (mid-1970s) in small dinghy sailing in Connecticut, won the regatta going away, I think.

I was reminded of this windspeed issue by finding a picture of the late Bob Miller* driving an 18-foot skiff hard downwind under kite in one of the Sunday races on Sydney Harbor. He was standing in for the regular skipper for some reason. It was, judging by the speed of the boat and the look of the water, blowing the oysters off the rocks that day. A black nor’easter, we called them, just like Newport’s smokey sou’wester.

One of the calls anyone dealing with kids and sailing must make is when to NOT sail based on windspeed. In my new parent documentation, I note that there is AWAYS sailing and most of the time it is in the boats. A few days a season we do chalk talk, or like yesterday we did sail shape and design and shape adjustment on a boat, sail up but with the boat rolled over 90 degrees so the sailors can see sail shape from the top down amongst other things.

My criteria for sailing when the wind is up is NOT that it is too windy for the skilled kids to sail. Rather, it is the effectiveness of the time on the water. If one goes in the drink, quite often it takes up too much time to recover them and everyone else is reaching around flapping sails and getting cold. Righting a capsized boat is all part of the sailing experience but if I get two of them over, then things start to get a bit interesting.

When we sail in fresh breeze, I have a briefing along the lines of, “We are just going to sail, get used to boat handling in this much wind and sea state.” If someone goes over – and I remind them (with fingers crossed) that it’s perfectly possible, part of the game, and not a slight on your abilities – I assure them that every world champion and Olympic medal holder in dinghies has capsized at some point. If one boat is over, everyone else must stop and heave to. Back the jib and sit tight. If two boats go over, the rest must sail to the dock, drop the mainsail, and stand by. I appoint a leader to run things on the dock in this situation.

When a dinghy capsizes, I give the crew five to seven minutes to right the boat, or three tries. I will idle up to them, first making sure I can see both sailors, and say nothing, or maybe shout, “You OK?” Almost universally I get a smile, a thumbs up, or a nod. Reading body language is a good skill for coaches to have here. Once in a while, the sailors cannot right the boat. Either they are too light and/or the mast is full of water, or more commonly the mast is in the mud. In the wind conditions where this is going on I will have a pretty skilled driver regardless of the skills of the crew. If I decide they have had enough, I come over to them and tell them what I am going to do.

This usually involves getting the crew into the RIB first. Making sure they are OK, not too cold, breaking out the hand warmers and/or towel as needed. I have by now put the RIB alongside the turtled boat with the towline in hand, and get the skipper aboard the RIB too. It is pretty simple to grab the centerboard and right the dinghy from here. I make sure I am telling the sailors with me in the RIB what I’m doing AND why, and what I need then to do. Not so much because I need the help but because it involves them. “This is seamanship,” I announce – not actually sailing but joined at the hip to sailing. Once the boat is upright, depending on the conditions and what the crew is feeling like, I will either turn them loose again or take some other action.

I am thinking of this related to exactly a situation a couple weeks ago. I had the “Training Squad” out – the less skilled sailors, sailing as crew with a Regatta Squad skipper. The breeze was brisk but sailable. I might note, never have the group as a whole hesitate about the windspeed. Some will push it: “Let’s go sailing.” Some will say they don’t feel comfortable steering. I have previously told everyone, “If I ever ask you to do something you are uncomfortable in doing, tell me.” And they do. “YOU are responsible for going to sea, or not,” I say, touching on RRS 3. I Mention RRS 1 also.

Anyway, this day we had six boats, twelve sailors and a fresh NE breeze. We sailed upwind from the Volvo Docks (I guess they are now The Ocean Race Docks), over to Newport on long boards. Speed testing. Hiking techniques, sail trim, steering in the puffs are all fodder for my bellowing instructions. We stop for a rest under the lee of IYRS, bail the boats out, reach back downwind, repeat.

After about the fourth or fifth lap of this sailing the troops were getting weary (body language read again), I signaled to return to the docks. We had had a good workout and the sailors had done well. I was idling along behind the flock when one of the boats capsized and turtled. I looked at the rest of the boats and they were all apparently under control, so I detoured over to the upside-down boat.

The skipper was one of the crew (usually) on one of the top boats on our team, but he will steer at the asking. The crew was one of the newer team members. (In an evening email to his mum inquiring about his experiences, she reported she told him she was glad he was “blooded.”) I watched for a few minutes, and it was obvious the mast was again full of water and a combined weight of 260 or so was inadequate to the task. After a few minutes watching them, I called it, and executed the plan described above. The skipper, Carter, I took into the RIB with me, and I explained what I wanted to do and what I needed of him and the other two sailors – I had a spare crew already in the RIB. This was done quietly with no dramas and the boat came upright.

At this point the cloud cover had brought an increase in windspeed. The crew was looking a bit cold, so I decided I was going to tow the boat in. I asked Carter to climb into the boat and lower the mainsail. I still had the dinghy alongside and motored gently head to wind. Of course, the main halyard had become a bit tangled in the capsize and he was having a hard time pulling the sail down and handling the halyard. I wanted to get going into the dock, so I told him to just let go of the halyard and concentrate on pulling the main down. In a classic example of too much haste and not enough thinking, the halyard got jammed with the mainsail still about four feet up the mast. Humph. “OK Carter, just lash the mainsheet around the sail boom.” Done with no further instruction needed. At this point I thought he could sail the boat in under jib alone and asked him if he was OK with this. “Sure!” says he. I give him a pointer or two and let him go.

Every once in a while, something sticks up out of the ordinary amongst the same old same old of daily practice. Watching Carter casually sail his charge in under jib only was one of those little memories that sticks. He was as content and capable as the Ancient Mariner, jibsheet in one hand, hiking stick in the other, sitting slightly inboard looking like he could do this all day and night.

Into the head of the cove the breeze was abating, becoming light, but nonetheless he sailed the boat up to the docks and came alongside like he had been doing this forever. All the rest of the Chickadees were in various stages of unrigging, so I docked the RIB and went on with my getting the boats tucked up rounds.

At the debrief, I congratulated them all on a good workout in tedious conditions and for being so comfortable in the boats. And I also pointed out how I had screwed up by telling Carter to release the halyard, for it was this instruction that got the halyard stuck preventing him from the getting the main all the way down. Teaching moment: “Don’t let your desire for speed interfere with calm action,” I remark. “My fault,” I told them. “Even coaches are not infallible,” I suggest.

As usual they were all smiles, bantering with each other, and when excused for the day, thanked me, as they always do. None of this memorable day would have happened if it were blowing too hard to go sailing. ■

Australian born, Joe ‘Coop’ Cooper stayed in the U.S. after the 1980 America’s Cup where he was the boat captain and sailed as Grinder/Sewer-man on Australia. His whole career has focused on sailing, especially the short-handed aspects of it. He lives in Middletown, RI where he coaches, consults and writes on his blog, joecoopersailing.com, when not paying attention to his wife, dog and several, mainly small, boats.

* More widely known as Ben Lexcen, designer of Australia 2.