By Tom Darling

In the fall of 2020, we followed in the wake of an iconic yachtsman, photographer, raconteur, all-around waterman, and tropical sailing pioneer. That would be Carleton Mitchell, born in 1910, who filled the 20th century with the writing on sailing that defined the activity of “cruising.” “Mitch,” as his friends called him, was a modern day Odysseus; his quest was to show the West Indies, its water, its people, its boats, to a curious boating public.

Above: Carleton Mitchell photo of 1960s log canoe

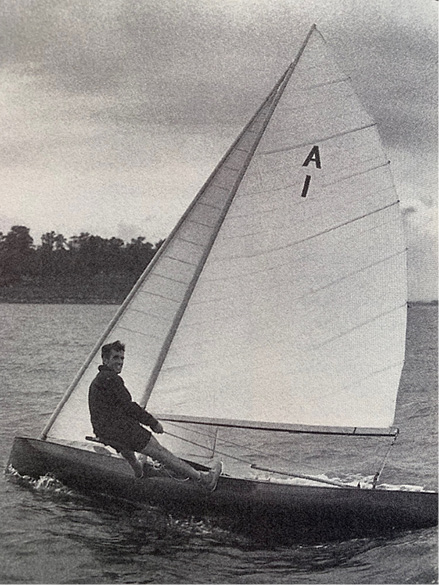

Left: Uffa Fox sails his decked canoe, East Anglican, 1920s.

What most of us did not know about is the vast trove of photographs that Mitchell produced, a collection which is curated in his archive of over 20,000 images at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, CT. Much of it documents the native boats of the Americas. It is this archive that drew me to explore not just the photos but also marine art of the iconic Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe, one of the most spectacular American native watercraft.

Native designs were always a fascination for Carleton Mitchell, whose beloved Finisterre was a three-time consecutive winner of the Newport Bermuda Race (a race that resumes here in June). He extensively photographed the boat most closely associated with his home waters, the Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe. We counted dozen of images of this iconic design, work boat turned into exotic racing craft, in the MSM archive dedicated to his life’s photography legacy.

My guide for exploring Carleton Mitchell has always been my good friend Chris Freeman, head of advancement at Mystic Seaport Museum. Chris, along with John Urban of New England Science & Sailing, encouraged me to start the Conversations with Classic Boats podcast. I would never have figured out the Riddle of the Boston Whaler without his access to the files of the reclusive John Barry, lead designer of the Hickman SeaSled Company, Devonshire Street, Boston. In 2020, Chris put a comprehensive and entertaining show on Mitch; with his 88-page presentation, he toured the pre-pandemic East Coast bringing Mitch and his many lives to yacht club audiences.

One thinks of Mitch as a blue water sailor but he was the product of lakes, ponds and bays, starting with his early life in New Orleans. What we also tend to forget is he was first and foremost an accomplished self-taught photographer. In the MSM is his archive of boats of the Americas writ large, North and South. And the craft common to all of the Americas, the sailing canoe, is exemplified by his photographs of the Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe.

One should never forget that for years the hailing port on the transom of Mitch’s boats was Annapolis, home of the U.S. Naval Academy. Mitch’s connection to the Navy dated to World War II, when he took photos and taught others how to do it as well. There are only a handful of his actual active duty pictures, and those are of planes and carriers, not boats. But the Navy sharpened his eye and when he returned to the States, Chesapeake Bay was one of his first photographic beats. The other was the islands of the Bahamas.

One sees in those pictures of small boats two recurring locations: Nassau and the Chesapeake. In both locations he was careful to document the local class, what I would call the native boat. In the Caribbean, it was the fishing smack: high sheer, beamy, shallow draft. In the Chesapeake, the boat that caught Mitch’s eye was perhaps the oldest design in North America, derived from a Native American model hundreds, maybe even a thousand years before. That was the canoe, the sailing canoe and its ultimate incarnation, the Chesapeake Bay Sailing Canoe.

The Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe in light air on the Bay

This was one of America’s work boats transformed into a recreational rocket, ultimately designed and built for pleasure sailing and especially for racing. Indigenous to the light winds and shallow grounds of the Eastern shore of Maryland and the lower Chesapeake Bay, the log canoe is in fact from the sandbagger genus. These are boats with powerful hulls, clouds of sail and human ballast moving weight to counteract that sail power.

Look at the pictures of a log canoe in the Mitchell archives. On the surface it looks complicated. Two masts, and a huge bowsprit half the length of the hull. Technically a ketch, that due to the boat driver sitting behind the mizzen mast. Very often a topsail on a sprit extending the main mast, and as many as two mizzen trimmers perched on a stern sprit a couple of feet above the stern wake. A baker’s dozen as crew.

But the signature characteristic of the log canoe, one that may date back to Native Americans, is the array of hiking boards, sometimes called “springboards” for the their flexibility, where the half dozen meatiest crew members perch at the directions of the helmsman. This is the log canoe’s distinctive feature and it was one that would be applied to many undecked and decked sailing canoe designs.

Sailing canoes with a moveable hiking board, known as a “sliding seat,” were built and sailed by acrobatic sailors from the 1870s up to today. No yacht is this; this is all boat and a historically high tech one to boot. The whole effect of a sailing canoe is of a fireman’s hook and ladder vehicle with the skipper and crew hanging on for dear life.

The log canoe is perhaps the purest and most advanced model of an American design type that brought thousands to sailing in the late 19th century. In that period, there were two kinds of boating clubs. There were yacht clubs and there were canoe clubs. One was for the well to do primarily, the other a working man’s establishment.

I happen to sail an International One Design (IOD) out of a former canoe club, Horseshoe Harbor YC in Larchmont, New York. Pictures of the club from the 1880s depict eager sailors rigging their sailing canoes and small catboats. Leading canoe racers made Horseshoe Harbor their skunk works for canoe innovation. Even today, HHYC is a haven for kayakers and other paddlers.

But the democratization of canoe sailing was linked to the explosion of decked and undecked small sailing craft with a unique invention for wielding human power known as the sliding seat. The encyclopedic Mystic Seaport Watercraft Guide has as its next to last section a survey of sailing canoes. Designer and self-designed decked sailing canoes proliferated on fresh and salt water.

Even famous designers like Starling Burgess took a crack at designing a canoe. In 1906, Burgess joined the American Canoe Association and built a pitch-black canoe called Twilight. Between then and 1920, he introduced his protégés L. Francis Herreshoff and Norman Skene to the pleasures of paddling and sailing in canoes (is it possible that L. Francis’ canoe-sterned designs were the result?) (Reference: Mystic Seaport Watercraft, p. 371)

More sophisticated models, with rig, hull and sliding seat, developed through the 1920s. They were incorporated both in the U.S. and in the designs of one Uffa Fox in the UK. A polymath wonder of sailor, designer and author, Fox became the godfather of the modern planing dinghy. The photo from Mystic’s Watercraft Guide shows Fox with his East Anglican decked dinghy in 1933. Fox became the designer of such early planing boats as the Flying 15 in the UK. The shapes and the rigs were all derived from canoes.

It was those same 1930s that marked the golden age for the Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe, with a revival of building new replicas on the lines and with the rigs of the old workboats. By whose hand and how did this craft evolve? This is a workingman’s boat adopted by the classic boat fan. Its ancestor, the canoe, is the creation of Native American culture: long, skinny, efficient, unstable. All of that gets translated into the sail-powered version that we know as the Chesapeake Bay Log Canoe.

This Charles Raskob Robinson painting depicts modern log canoe racing on Chesapeake Bay.

On the Bay, the log canoe was a working boat derived from the single-log dugouts of the Native Americans. They were the working boats used by oystermen, but enlarged by adding a log to each side, and then later, more logs, becoming what Gregory Jones describes as “a three- or five-log canoe.” They were exceedingly tender and balanced by shifting human ballast or cargo. Substitute humans for ballast and the Chesapeake watermen raced them, at first with their catch back to port, but also for the sheer thrill of racing.

(Reference: The American Sailboat, Gregory O. Jones, p. 250)

This excerpt from Gregory Jones’ The American Sailboat, a book I highly recommend for its breadth and depth explaining the evolution of small boat design, tells the story of the evolution of Chesapeake Bay designs:

“The line of evolution began with the log canoe, a centerboard boat built of logs, pinned together to form the hull. Some boats had two sets of sails, a working set, small enough to handle with a load of oysters, and another, larger set of racing sails. Log canoe races began as entertainment for the watermen, who would bet on their favorite, on the local rivers (including the Chester, the Miles and the Tred Avon). The racing scene with log canoes slowly disappeared among the working watermen around the beginning of the 20th century but wealthy yachtsmen adopted the boat in the 1930s, commissioning log canoes built for racing.”

The picture from The American Sailboat is of Jay Dee, a 1931 canoe built by John B. Harrison. It sports an impossibly tall rig and the trademark opposed wishbones (think Windsurfer boom) keeping the main and enormous mizzen taut. The picture shows two crew “out on the boards” and the ten other crew ready to move to keep the boat upright.

Another 1930s vintage canoe, the Flying Cloud, demonstrates the delicate balance between power and control in a modern log canoe. Winner of the Bay Championship Governors Cup in 1934, she was gradually reduced in rig in 1940s as a daysailer, then restored to turbo power in 1975 when she came back into competition.

The John B. Harrison yard, called “Devil’s Island” and located at Tilghman Island in the southern Bay, was commissioned to do these two boats, Jay Dee and Flying Cloud, along with the Edna B. Lockwood, a canoe recently restored at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. Harrison himself was a larger than life character as both builder and sailor. He was alleged, when asked to reef during a race, to have said about the sails, “Just let the wind blow them off.” He built his first Chesapeake Bugeye, the iconic Bay working boat design, in 1882. In the 1930s, he built his series of log canoes strictly for racing, the three cited above in addition to his own John B. Harrison, Barbara and Albatross, the only log canoe with two centerboards, fore and aft (a premonition of modern offshore boats like Australia’s Rolex Sydney Hobart Race winner Wild Oats).

Visitors to the St. Michaels-sited museum gawk at the display of these splinter-hulled structures with hiking boards and towering rigs. They are the ancestors and carry on the design DNA for working boat designs on the Chesapeake as the Brogan, the Skipjack and the Bugeye. Log canoes were being built well into the 20th century, the later ones for pleasure boating only. There is no richer tradition on the Chesapeake than the racing of log canoes. In August, they come out to play on the Bay in their annual regatta.

Mitch loved the look of these boats, the racing versions and the working boats. He created a similar portfolio of the native Caribbean design, built to carry cargo, not to race, but then adapted with taller rigs and bigger crews along with voluminous downwind sails, to race for prizes and cash. He captures those same working boat characteristics in the sixty or so prints of log canoes out of an archive of over 20,000 images. He has the same affection for the Caribbean skiff and the log canoe. He sees clearly one is a packhorse, the other a thoroughbred.

Those thoroughbred genes come through in extraordinary paintings by Charles Raskob Robinson, a member of the American Society of Marine Artists. Charlie is a longtime member of that group along with Russ Kramer, who did the famous painting of Mitch’s Finisterre in the stormy waters of the 1960 Bermuda Race. In the painting on these pages, he captures the essence of an iconic design. There is the log canoe, driver white-knuckled, crew out on the hiking boards, hoping they have the right driver. And most amusing, like the rear driver on a fire engine, the mizzen trimmer sits in a woven seat hanging it out over the stern. It’s a sandbagger with no freeboard and no beam. An unstable concoction of wood and canvas, held together nervously by we hope a veteran crew.

For those of you interested in exploring the Carleton Mitchell Archive, it is available through the Mystic Seaport Museum website. Don’t blame us if you while away hours on thousands of Mitch’s photography. From West Indies scenes to racing offshore, they are waiting, like the Caribbean was for Mitchell after World War II, to be discovered. ■

Tom Darling is the host of Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.