Story & photos by Nico Walsh, Cruising Club of America, Boston/Gulf of Maine station

Far and Away in Loch Scavaig

In 1978, as a young college student in London, I found myself emerging from a Dockyards bookstore owning a copy of Eric Hiscock’s Wandering Under Sail (1939). Hiscock and his wife Susan became famous for their extensive voyages and their cruising accounts and manuals, including Voyaging Under Sail, Sou’West in Wanderer IV, and many others. I have since read most of those books, and it is fair to say that my 1978 bookstore encounter with Hiscock played a vital role in the development of my cruising aesthetic — an aesthetic that seeks cruises well-ordered yet adventurous and a life aboard both simple and gracious.

In June of 2023, my cousin Marta Downing and I sailed Far and Away, my Cabo Rico 34, from Martha’s Vineyard to Cork, a swift, drama-free passage of 22 days, average noon run 139 miles. My wife, Ellen, joined, and after a cruise of Ireland, we hauled at the Clyde Marina in the Firth of Clyde, an excellent and reliable yard, though exposed to gales on the hard standing.

The Loch Scavaig anchorage. Far and Away is the near yacht.

In May, we returned, ready to cruise Scotland’s west and north. In planning our summer, I thought back to Hiscock and in particular to his long essay, “Alone to the Isle of Skye,” found in Wandering Under Sail. Suppose we visited many of the same places where the young Hiscock sailed in 1938, to see what had changed and what had not and to view those places through the lens of his experience?

Our first navigational challenge was the Mull of Kintyre. Scotland’s west coast is marked by forbidding headlands with well-deserved reputations for swift currents and rough water, and to go north we had to round the Mull. Many folks stage at Campbeltown — one experienced Scot told us he anchors there and, no matter the hour, if the wind drops and the tide will be fair, he guns it around. We instead called at Sanda, just three miles west of the Mull. We anchored in strict accordance with the instructions in the Clyde Cruising Club’s excellent guide, and though swift currents swirled a few hundred feet away and the winds gusted, our spot was quiet, safe, and with sand bottom, though on a lee shore. The island is private, and while recent scuttlebutt suggests boarders will be repelled, on our walk ashore we encountered no resistance. We even gathered some periwinkles.

Our strategy for rounding the Mull was successful, an early departure to arrive at the critical area just as the fair tide would begin, and the winds would be reasonable. It was no more than choppy, just the way we like it.

These headlands all feature an area of rough water off the point, and one strategy is to go far enough offshore to avoid the rip. Another — widely endorsed if one can believe it — is to make the transit 10 meters from the rocks in what is said to be smooth water. We heard of this strategy again and again. Not for me, thanks.

Our next destination was the island of Gigha (“Geeh”). We had a fair tide the whole way and anchored off the village in shelly clay. We hiked ashore, saw some sarsen stones, did a shop, and drank a pint in the pub — perfect.

We hadn’t yet crossed paths with Wanderer, but caught up with her in Tayvallich, at the north end of Loch Sween, off the Sound of Jura on the west coast of the Kintyre Peninsula. Here’s Hiscock in 1938: “I then sailed up the Sound of Jura … and in the evening ghosted up that glorious waterway, and at dusk slipped into the little lagoon of Tayvallich, which is the most perfect harbor I know of.” He got that about right. Tayvallich is eight miles up the narrow loch, there is little tide and no current within, and guarding the narrow harbor entrance are two islets, nearly overlapping.

We stayed two nights, one anchored outside and one on a mooring inside, so we could hike with a settled mind. It would be possible to anchor inside, but only just, for there are a good many moorings, a change from Hiscock’s day. But Hiscock found an attractive and convenient little village, and so did we. We also found cold weather and sharp squalls with ice pellets.

Our next destination was Craighouse, on Jura, which we reached after a stiff close fetch. We took a mooring here, the bottom being kelpy. We had a very fine hike up Glas Bheinen, route-finding across the boggy barren uplands and by black tarns, with an excellent breezy summit and a long view to the Isle of Mull and beyond. We were watched all the while by a herd of roe deer and, I have little doubt, by the little men who, as the poet William Allingham knew, abide in these places (see his “The Fairies”). Scotland was getting into our blood.

George Orwell spent most of the last years of his abbreviated life on Jura, living in a very remote farmhouse reached by a rough road and then a hike, and this is where he wrote 1984. Jura loves Orwell, and a local, Les Wilson, has just written Orwell’s Island, an account of the man and his relationship with Jura (I read it; an excellent book). We attended a party celebrating the launch of a gin, held in the community center, with good food, good music, and good drink and attended by islanders ranging from bearded academics to farmers. Les Wilson and his book were also there, as well as an artistic installation comprised of 1,984 unique volumes of 1984.

Far and Away in Bull Hole, with the north end of Iona in the middle distance

The next day, it was a charming close reach up the Sound of Jura and past the feared Gulf of Corryvrecken (Coirebhreacain), described by the Admiralty’s West Coast of Scotland Pilot as “very violent and dangerous,” currents reaching 9 knots, whose overfalls top 10 meters, and whose roar at full spate is reliably said to be audible 10 miles off. In 1938, the engineless Wanderer went by the Gulf stern first in a calm; our man “had to use the sweep vigorously to avoid being carried into that part of the flood stream which sets directly toward and through the Gulf.” We anchored in Kilchoan Bay in the Sound’s north end, off a great house.

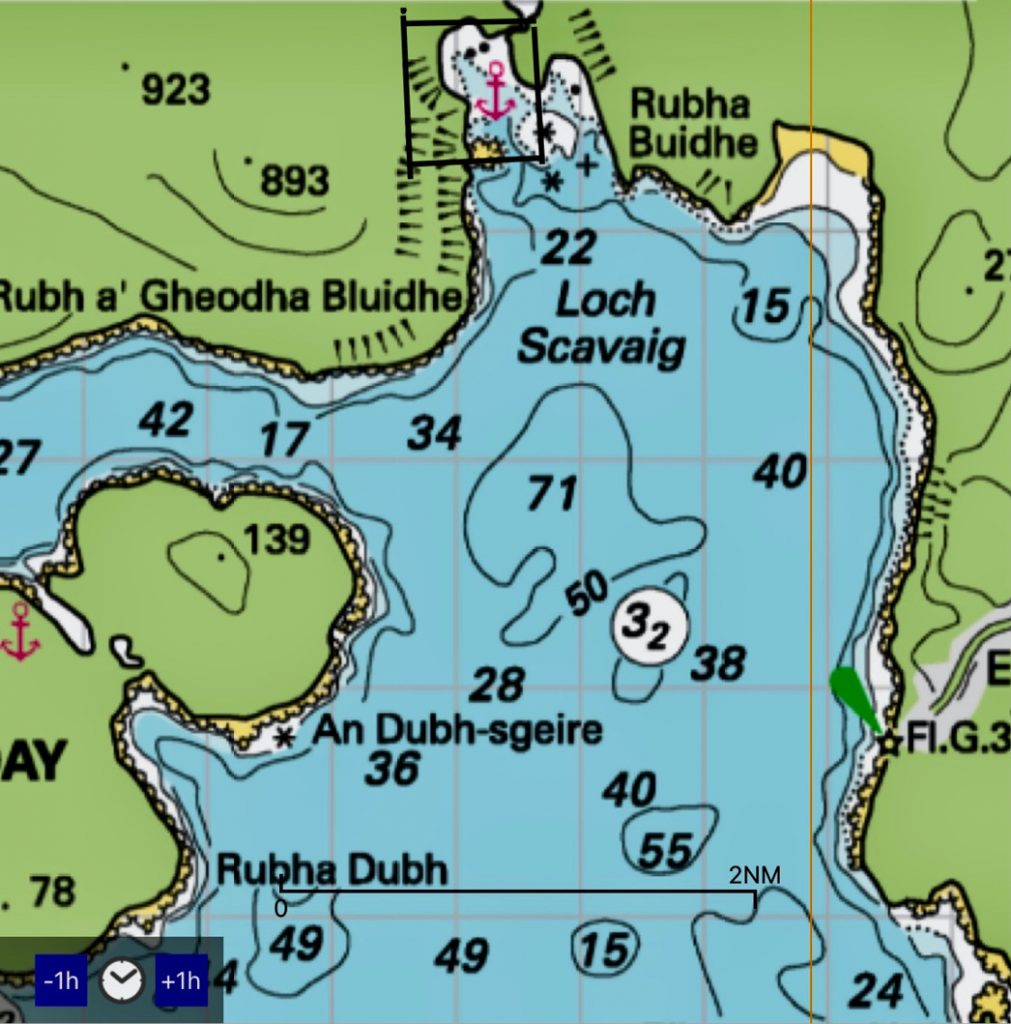

Loch Scavaig on the Admiralty chart

The next day, exiting the Sound of Jura, we had thought we might anchor in the slate port of Easdale, but the place looked grim and was said to have very poor holding, the bottom being, I suppose, little more than a slate floor. Instead it was the Puilladobhrain, “the otter’s pool,” famous even in Hiscock’s day, where in 1938 he “brought up in the wild little pool which had not a ripple on it and not a sign of human habitation anywhere around.” Alas, where Eric Hiscock had the perfect tranquility of the pool to himself, we found six other yachts there, and Far and Away made the seventh. A pretty spot to be sure, but very near the yachting center of Oban.

Our path and Hiscock’s diverged for a time, he heading toward Mull and we headed east, down long Loch Linnhe and toward Fort Williams, the western terminus of the trans-Scotland Caledonian Canal. Our goal, a rare spell of settled weather being forecast, was an ascent of Ben Nevis.

Ben Nevis, although the highest mountain in the British Isles, is only 4,411 feet. But long, nearly vertical routes furrow the famous north face, and climbing the Ben in winter, and perhaps in the sought-after heavily rimed “Scottish conditions,” requires skilled mountaineering usually associated with higher terrain. In the 1920s and ‘30s, young British climbers such as George Mallory and Sandy Irvine learned their craft there, before heading off to the Himalayas. The tradition of the Ben as an incubator of British alpinism continues to this day, and I wanted to see the north face.

Our path took us directly there, and we rested at the climbers’ hut, studying the famous Zero Gully, Orion Face, Tower Ridge, and others. After visiting the snowy summit (via the hiker’s path, assuredly), we hiked back to the boat, which waited for us at a downtown pontoon.

Our cruise then took us north up the Sound of Mull, rejoining Hiscock’s route. Like Hiscock, we anchored in Loch Aline, very well protected but with soft bottom (we used the Fortress when the Vulcan wouldn’t do) and, we thought, lacking any real charm. Tobermory, at the north end of the Sound, is a pretty town with all the conveniences. We picked up a mooring and shopped at a store selling whiskey, books, and fishing tackle.

We found ten inches of snow on the summit of Ben Nevis.

The following day was bright and calm, and we motored to Arinagour on the island of Coll, long, low, and barren, with a population of 190. On borrowed bikes, we crossed the island to the sandy, windswept north shore, and on a beautiful small bay saw lapwings, a new bird for us.

Our goal was now the fabled Iona, the route to which took us past Staffa and its Fingal’s Cave, the acoustics of which inspired Mendelssohn to write the “Hebridean Overture.” But Staffa is no place to leave an unattended yacht, so we sailed by.

That night we found ourselves in South Harbor, between Gometra and Ulva on Mull’s west coast. This anchorage is wild and well protected, except perhaps in a heavy southerly swell, and we had it to ourselves — Scottish cruising at its best.

Iona, just off the Ross of Mull on Mull’s west coast, is where St. Columba landed in the 500s and brought Christianity to Scotland. For many centuries, it was a center of learning, with a famous library and scriptorium: the Book of Kells may have been created or perhaps begun there. The island early developed a reputation as a place near to Heaven, and burial on Iona, many a king and chieftain believed, was a sure path to the good place. Iona’s monastic buildings are partially restored, there is an excellent museum, and the island remains a place of worship. It is worth a journey.

The anchorage off Iona is not particularly good (kelp and current), and we didn’t overnight there. Instead, we anchored across the Sound of Iona, in Bull Hole near Fionnphort, a crack between granite buttresses. Our use of Antares charts was key here, as it so often was in Scottish waters.

Antares (antarescharts.co.uk), which I understand is one man’s project, takes Admiralty charts of anchorages and passes and, using side-scan sonar, produces very large-scale charts with far more detail than the Admiralty charts, and with pilotage notes. We found them extremely helpful. The entire set is available, online only, for a single modest payment.

Our Garmin chartplotter was our main source of charting, backed up by an iPad with Imray charts. For planning, we had two small-scale Admiralty paper charts, one for western Scotland and the other for Cape Wrath to Orkney and Shetland.

As it happened, our daughter, her fiancé, and his family would be in Oban in a few days, and we had arranged a rendezvous. The sail down Mull’s south coast toward Oban was among the best I can remember, strong fair winds hurrying us along a coast with thousand-foot cliffs and waterfalls. We sailed just a mile or so off, for fun. We spent the night in Loch Spelve — good mud and good protection. At this point Ellen was feeling poorly, possibly with Lyme disease, and we made tracks for Oban, where she got good care at the local clinic.

While waiting for family to arrive, we visited Loch a Choire, off Loch Linnhe’s north shore. There is a great house there, Kingairloch, which takes paying guests. After trying and failing to find an anchorage (too deep, too steep), we picked up one of their moorings, free but please make a Royal Lifeboat contribution.

Kingairloch House made us very welcome, and we toured what is surely among the finest kitchen gardens to be found — big, beautifully arranged, productive, and surrounded by a towering wall. The North Atlantic Drift moderates Scottish weather, and Kingairloch grows artichokes.

The rendezvous was a great success. We stayed at the convenient Oban Transit Marina downtown and fueled at Oban Marina, on Kerrara across from Oban. Yachts using Oban Marina must be aware of a nasty wreck, badly marked, almost invisible at high water, and just 280 feet southwest of the fuel dock. It’s charted, but maneuvering yachts hit it with alarming frequency, and little wonder.

Currents in this part of the world are formidable.

Now it was time rejoin Hiscock, and we headed back up the Sound of Mull and past Ardnamurchan, the most westerly promontory on Scotland’s west coast, fully exposed to the Atlantic. Hiscock wrote that this headland “is so respected by Scottish cruising men that when a yacht has rounded it, she wears on her bowsprit or stemhead a bunch of heather.” We didn’t decorate Far and Away, but we saw yachts that were.

A gale was forecast, so upon rounding Ardnamurchan, we sailed deep into Loch Moidart to wait out the blow. Another yacht joined us in our already-cozy pool, and I made my concerns known, but he stayed the night.

It bears noting that almost everywhere we went on our cruise, including the Outer Hebrides, Shetland, and even Fair Isle, and often when deep in a loch, we had excellent cell reception. Hence, we could receive online weather forecasts as an alternative to scheduled VHF. We typically used the BBC Shipping Forecast and Windy, and a morning tradition was the homey and useful weather briefing video BBC Scotland Weather (@BBCScotWeather on X). You may even hear it in Gaelic.

It was a three-day blow, and we enjoyed it. There was the customary small castle on the headland that formed our little bay, we had walks inland, and at low tide a flat, sandy beach revealed cockles and mussels for the galley.

It was bright but still gusty when we left, and we had a lively beam reach to Loch Scavaig, on Skye’s south coast. Loch Scavaig is a special place, and Eric Hiscock’s two nights there are the dramatic climax of his cruise. The anchorage is small but ample for two or three yachts, and it is protected to the south by ledges. So while protection is in a sense good, towering right over the loch are the treeless and forbidding Cuillin Hills, several over 3,000 feet, and in a westerly storm squalls blast down from the peaks and savage the anchorage.

This was certainly Eric Hiscock’s experience, when suddenly rising winds made it impossible for the engineless Wanderer to chance weighing anchor and tacking out of the loch:

“As the day progressed the squalls became more frequent and furious, and fell upon us from all points of the compass, as often as not blowing vertically off the mountains, pinning the little vessel down with her rail awash, although by then I had stripped her of most of her running rigging. I had lowered the 56-pound weight down the chain, and it did something toward easing the snubbing, but again and again I felt sure the chains must part or the anchors come home, while the squalls tore round and round in that devil’s cauldron, whipping the spray from the sea and whirling it away to be lost in the low mist which made a roof in the dark pit in which we lay.”

With such a warm endorsement, how could we pass up a night in Loch Scavaig? We went ashore, visited the climber’s bothy with its memorial plaques and displays of ancient gear, and hiked up the mountain to a grassy ledge overlooking Far and Away, perhaps the very ledge where Hiscock writes of smoking a pipe and contemplating his little yacht in the quiet hours before Hell descended. Our night was tranquil, with just a few unsettled gusts to evoke what Hiscock endured. I got up again and again to gaze around me, the mountains so close, and replete with waterfalls.

After Loch Scavaig, Hiscock’s and our paths diverged, he starting on his long voyage back to Southhampton and we sailing on. Our cruise would take us east about Skye, to the Outer Hebrides and even to their west coast, to Stornoway where Cook and Franklin watered, to the Shiants with their clouds of puffins and where creation seems new, around Cape Wrath to Orkney, to Stromness and Scapa Flow where the German fleet was scuttled and where U-47 torpedoed the Royal Oak, to the Fair Isle and to Shetland. We had many an adventure, none bad and most very good, and Far and Away is now hauled in Scotland, awaiting May and another voyage. ■

Nico Walsh is an admiralty attorney living in Freeport, ME, and a former Coast Guard officer, merchant mariner and commercial fisherman. He and his wife Ellen cruise extensively on Far and Away, their Cabo Rico 34.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the 2025 edition of Voyages, the Cruising Club of America’s annual publication, and is reprinted with permission. Special thanks to CCA Commodore John R. Gowell and Voyages Editor Dan Biemesderfer.

The Cruising Club of America comprises more than 1,300 accomplished ocean sailors who willingly share their cruising expertise through books, articles, blogs, and onboard opportunities. Together with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club, the CCA organizes the legendary Newport Bermuda Race. With active involvement and support from its 14 stations and posts around the United States, Canada and Bermuda, the club focuses significant national and international outreach efforts on ocean safety and seamanship training through hands-on seminars. For more information, visit cruisingclub.org.