Editor’s note: This month’s missive precedes another in our next edition entitled ‘Get Used to Being in Front.’ “These essays are two parts of the same idea,” explains Coach Coop, who shared this wisdom with The Prout School Sailing Team years ago and continues to do so before the start of each season. “It’s the same philosophy of sailing and by extension, at least in my view, life.”

Why this essay? As you will read, and (continue to) learn as your life progresses, the way you think about things has a great influence on the outcome of “those things.” I feel pretty sure that you have had success in a variety of your endeavors. Some are sports, some are academic, and some are personal or emotional; all the flavors of life. Think back in your mind’s eye to the work you did leading up to those challenges, and what you thought about.

I’ll bet you a Snickers bar that the more positive, or perhaps more confident your thinking was going into the event, the better your outcome. There is considerable documentation supporting the idea that you are what you think about, some of it captured in books on this phenomenon. In my experience, the primary reason you feel confident is because you have done all the preparation. Whatever the event, task or challenge, you’ve put in the work before you got to the “starting line.”

This essay and its companion next month are an example of first a non-success, and then a massive success, after a year of training. They stem from a question put to me during a Finn regatta in January, 1976. The concept encompassed by this question had a huge impact on me and my life. I share these recollections with you because they paint the picture of how that single question shaped my life. I want you to know about it because it will help you with everything you do, including sailing. And it’s not impossible that thinking on these two stories might help you in your sailing in 2025, and beyond. Read on.

In October of 1975, I was working for Elvstrøm Sails Australia, a sailmaking firm named for one of the greats of sailing, the late Paul Elvstrøm, a Danish sailor who won four gold medals over the course of his eight Olympic Games career. And the Olympics were just some of his successes. More than one sailing writer suggests Elvstrøm created the idea of physical training for sailing.

One day in early summer in Australia, a fellow had come into the loft and was speaking with the loft owner, one Mike Fletcher, aka Fletch. This fellow, Tony James by name, had come into Elvstrøm Sails to speak with Fletch about something or another, sails likely. Fletch invited me over to meet him. I knew who Tony was, but had no reason to believe he knew anything about me.

Fletch said, “Coop, you know Tony James?” I muttered something about, “I know who you are.” We shook hands and he was cordial and inquired how I was, the usual drill. Without much ado he asked, “What are you doing on Saturday?” Before I could compose an answer, he said, “You’re coming to Woollahra Sailing Club (on the harbor in a Sydney suburb) to sail Finns.” “Ah, OK,” I muttered/nodded, completely taken aback.

This bloke, who had so kindly instructed me to come and join in sailing the hardest dinghy class in the world, was a veteran Sydney Finn sailor and a member of the 1972 Australian Olympic Sailing Team. I don’t know precisely what he and Fletch spoke about before I was summoned, but considering I was 6’4”, 190 pounds, young and fit, getting an invite – actually an instruction – to sail a Finn was not such an off the charts proposition.

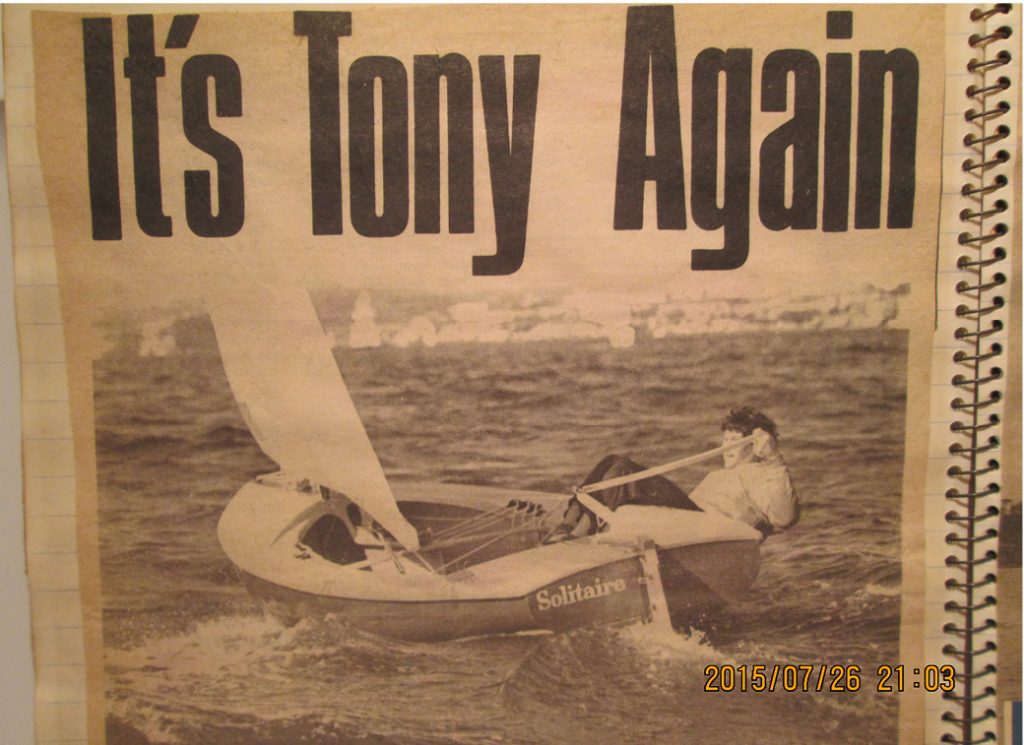

Over half a century ago, Australian Finn sailor Tony James was a top gun in this demanding 15-foot singlehander because he was the fittest guy out there. From The Cooper Archives

Plus, it was known locally I was a pretty good Laser sailor. I spent the next couple of months sailing Tony’s “old” Finn. He had recently acquired a much newer one. You have heard the phrase “steep learning curve.” The picture in the dictionary illustrating this proposition is of me sailing a Finn.

Fast forward to January 1976. The Finn Gold Cup, the World Championships, was held in Brisbane, Queensland, about 600 miles north of Sydney. There was another regatta prior to the start of the Gold Cup, the Australian Olympic Trials. The winner and second place skipper in those trials would be selected as part of the Australian Olympic Sailing team for the 1976 Olympics in Canada. Big doings fer sure, so all the top guns would be there. I was not a top gun, but the chance of two big, competitive regattas in fourteen days was something not to pass up. A world championship regatta does not come to within 600 miles of you all that often.

Knowing this, I started spending more time sailing the Finn, running, surfing, and swimming. Swimming is good exercise for anything, even Finn sailing. Finns are extraordinarily hard boats to sail, well, and fast. They are 15 feet long, heavy, with one mast/sail, and rely on serious hiking to make them go fast. There is also an intimate relationship between the sail and mast, as well as the sailor’s fitness, size, and weight.

For an excellent example of sailing in general, sailing a Finn in particular, and specifically the physical demands the Finn imposes, watch “Oli Tweddell – Australian Finn sailor,” a superb short film by Ben Hartnett that’s available on YouTube. I cannot watch it too often. Not only is it the best sailing video I’ve ever seen, and that covers a lot of territory, it’s an excellent depiction of sailing a Finn and the requisite physical effort. Stick with me here, this fitness discussion will play out in the second essay.

To touch on just one small sample of the sail loading, and so the fitness and strength needed to sail a Finn, contemplate this comparison. The mainsheet load to the skipper’s hand when sailing a 420 upwind in 20 knots is 87 pounds. This load, young sailor, you have experienced. In a Finn, it is 187 pounds. That, you have not.

Next time you are at the gym, set up the machine to move 87 pounds, and then 187 pounds, from the position you would be sitting in while hiking. We did a hiking bench drill last spring, and I set it up with about a 20-pound weight. Most of you found that more than enough, I recall. Onwards.

Australian born, Joe ‘Coop’ Cooper stayed in the U.S. after the 1980 America’s Cup where he was the boat captain and sailed as Grinder/Sewer-man on Australia. His whole career has focused on sailing, especially the short-handed aspects of it. He lives in Middletown, RI where he coaches, consults and writes on his blog, joecoopersailing.com, when not paying attention to his wife, dog and several, mainly small, boats. ■