Celebrating the return of eelgrass (albeit one blade at a time) to Smithtown Bay are (l – r) Associate Soundkeeper Emma DeLoughry, Long Island Soundkeeper Bill Lucey, and Rob Vasiluth of SAVE Environmental. © SavetheSound.org

The only thing more challenging than the water temperature – a biting mid-50s on a late May morning – was the turbidity. Already unable to see much beyond her outstretched fingertips, Emma DeLoughry resisted the temptation to feel her way along the sea floor; stirring up the sediment would have made it even harder to find what she was searching for in the muddy, murky waters of New York’s Smithtown Bay.

Emma spotted two horseshoe crabs and followed them. Glancing down, she noticed she was passing over a couple of empty clam shells. One had seeds glued to it. “I knew I was somewhat in the right area,” said Emma, the Associate Soundkeeper for Save the Sound. “Then, when I saw a partially submerged clam with a two-inch blade of eelgrass growing off of it, I was so happy.”

She flicked on the GoPro strapped to her right wrist and captured the moment. It was the culmination of the unique combination of roles she had played throughout the first year of an eelgrass restoration collaboration by Save the Sound, SAVE Environmental, and the Cornell Cooperative Extension. As she was participating in every phase of this innovative attempt to bring eelgrass back to a part of Long Island Sound where it once flourished, Emma also served as its documentarian.

“There’s never a time when I’m purely filming or purely a scientist. I’m always wearing two hats, taking turns between being an observer and an active participant,” said Emma, whose documentary, A New Method for Eelgrass Restoration, debuted on July 27. Produced with the support of 11th Hour Racing’s grant program, funded by The Schmidt Family Foundation, it’s available on Save the Sound’s YouTube channel (@SavetheSoundCT).

“There has been such a decline in eelgrass populations in Long Island Sound that so much of the general public – especially younger generations – have never been exposed to it,” said Emma. “This is such a visual story, and I think that’s helpful in increasing awareness and helping solve this issue.”

Ninety percent of Long Island Sound’s eelgrass has disappeared. It plays such a vital role in the ecosystem – sequestering carbon (even more effectively than terrestrial forests), providing food and habitat for a ton of aquatic species, combatting coastal acidification and erosion – that restoring eelgrass is an effort worth undertaking. Which makes it a story worth telling.

Emma has documented environmental issues before. While pursuing her Masters, she focused her thesis on plastic pollution in the waters of Columbia, SC. And she figured that there was a way for her work to reach beyond the typical audience for a Masters of Science project.

“I knew how much better it would be as a film,” said Emma, who grew up taking videos of friends on old camcorders and editing them on the family computer. “To me, it’s all about turning scientific data into something more visual and understandable. We saw plastic bags stuck in trees, tons of plastic garbage outside outfalls and pushed up against dams. We brought that straight to the public and showed them exactly what was happening in their waterways.”

Macroplastics in South Carolina Waters was Emma’s first documentary and her introduction to the opportunities at the confluence of environmental science and environmental storytelling. It launched a career in which she is both doing the work and sharing that work with the world.

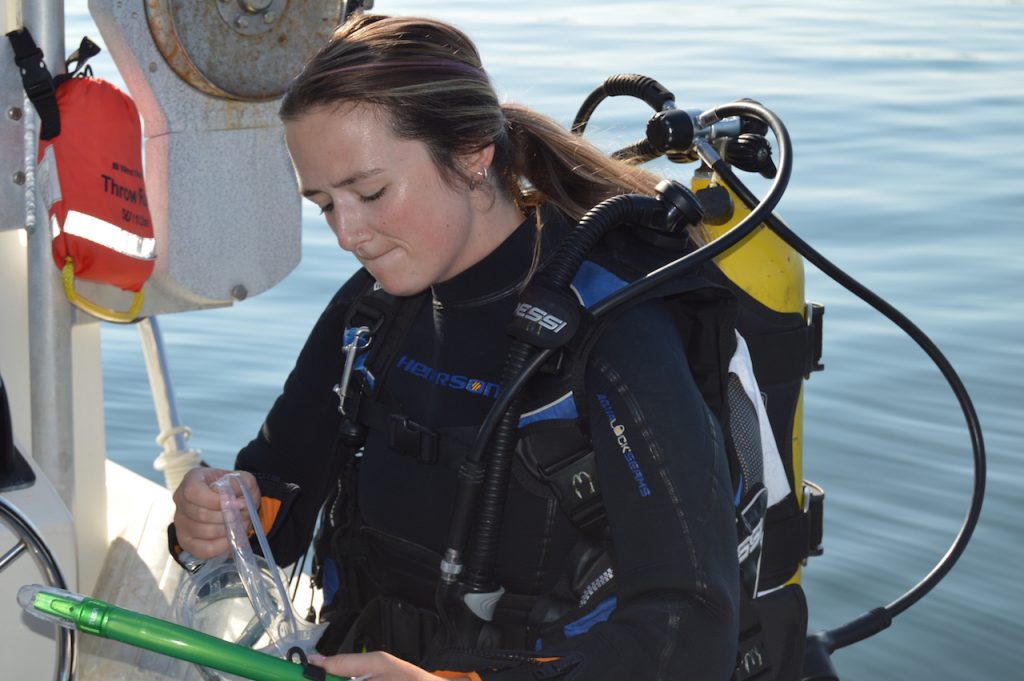

That’s why she became certified as a diver just days before the first outing to Fishers Island last summer. She wanted to be all-in on the restoration project from the get-go. Alongside Rob Vasiluth of SAVE Environmental, Emma dived through the most abundant eelgrass meadow remaining in the Sound, with a green mesh bag for collecting eelgrass shoots in one hand and a GoPro in the other. She pulled similar double duty through all subsequent phases, which included gluing seeds to the shells of clams at Cornell Cooperative Extension’s facility in Southold, deploying those seed-carrying clams off Sunken Meadow State Park the day before Thanksgiving, and then returning in the spring to document that lone green toothpick poking up from the floor of a two-acre parcel of the Sound where the clams had been dropped a half-year before.

“When I saw it, my first thought probably was, ‘I gotta get this shot,’” she said. “I whipped out the camera before I floated away and lost sight of it.” Over a series of follow-up dives this summer, no other signs of eelgrass could be found. Only the occasional empty clam shell, sprinkled with seeds, making Emma’s singular find that much more remarkable.

Still, the experiment continues, with plantings planned for this fall in other parts of the Sound, where conditions should be more conducive to successful sowing. And thanks to Emma, we’ll all be watching. ■