Find out in the 2024 Long Island Sound Report Card

Save the Sound’s crew collecting water quality data in New Rochelle Harbor for the Unified Water Study

How’s the water? It’s the question Save the Sound’s staff are asked more than any other. And it’s one that requires a nuanced answer, depending on what “water” you’re talking about.

The 2024 Long Island Sound Report Card, which we released on October 10 at multiple press events across the region, provides answers about the ecological health of the Sound, evaluating how well the water can support aquatic life. (That’s different from our Long Island Sound Beach Report, another biennial report in which we use other data sets to measure water quality at beaches according to state-established safe-swimming standards.) See? “How’s the water?” has no single, simple answer.

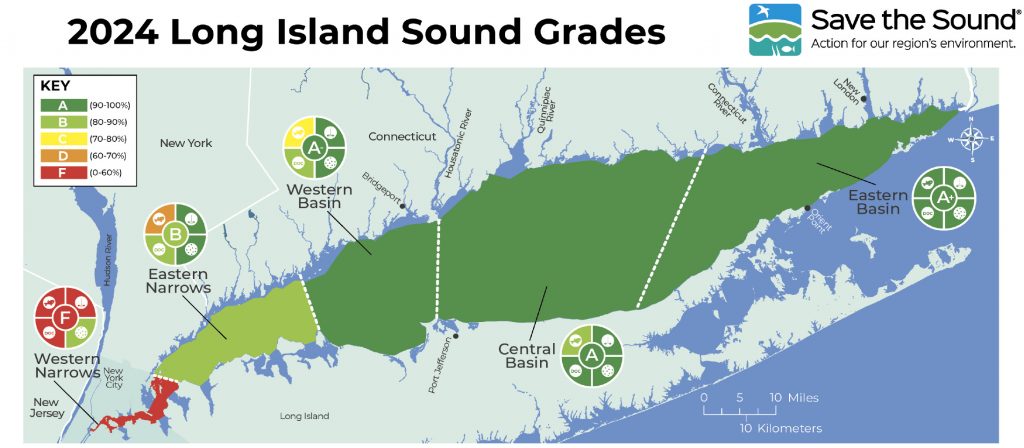

The 2024 Report Card (available for download at savethesound.org) issues grades based on data collected during the 2023 monitoring season for all five segments of the open Sound (from the Western Narrows in New York City to the easternmost boundaries of the Eastern Basin from Orient Point in New York to the Connecticut/Rhode Island border) as well as bays and harbors along the margins. And if you’re asking how’s the open water of Long Island Sound, you’d be pretty encouraged by the answer.

Moderate improvements in dissolved organic carbon and chlorophyll a (two of the five water quality indicators) contributed to the Eastern Narrows’ overall grade going from a C in 2021 to a B in 2023. That means 98% of the open waters of Long Island Sound received a B or better, making for a mostly green Report Card map. Even the Western Narrows, which received another F (as it has every year dating back to 2008), is showing signs of moderate improvement over a 16-year window. These encouraging trends can be linked to decades’ worth of effort and investment to reduce nitrogen pollution in Long Island Sound.

The bay grades tell another story. Fifty-seven bay segments received grades in the 2024 Report Card, including six locations getting their first scores: five in Connecticut (Mumford Cove, Poquonnock River, Guilford Harbor, inner and outer Bridgeport Harbor) and one in New York (Westchester Creek). Forty-two percent of them received a C, D, or F grade based on 2023 data. Bays and harbors are monitored by 27 groups as part of the Unified Water Study, launched in 2017 by Save the Sound to better understand the challenges these near-shore bodies face that differ from the open water and from each other.

A very encouraging 98% of the open Sound received a B grade or better in the 2024 Long Island Sound Report Card, but there’s much work to be done in the waters of the Western Narrows.

Nitrogen pollution threatens bays to varying degrees from a variety of local sources, whether it’s onsite septic systems on Long Island and along southeastern Connecticut, excess lawn fertilizer in Westchester and Fairfield Counties (where aging infrastructure is also a problem), or stormwater runoff, a growing issue as storms increase in frequency and severity due to climate change and as the region is more and more paved-over.

The most pervasive problem in bays remains hypoxia, which occurs when dissolved oxygen levels are too low to support life; fish die-offs in the hot summer months are an unfortunate but not uncommon consequence. High levels of chlorophyll and excess seaweed are companion stressors that also are prevalent in bays and harbors.

“It’s crucial that we continue to measure the water quality of the Sound on an ongoing and consistent basis, and report on the results so that action can be taken to protect and restore it,” said Peter Linderoth, director of water quality at Save the Sound.

Really, that’s the purpose of these reports—to provide answers, yes, but also to identify where there are questions. The information in the Long Island Sound Report Cards published over the years has provided elected officials in Connecticut, New York, and D.C. with persuasive data to shape policy and secure state and federal funding for projects that reduce nitrogen pollution and protect water quality. These solutions range from investing in wastewater and stormwater infrastructure upgrades, to installing green infrastructure, to restoring wetlands.

“It’s clear that past investment in nitrogen pollution reduction from wastewater infrastructure is linked to improving the open waters of Long Island Sound. Now, our challenge is to find the political will to extend and expand this investment,” said David Ansel, vice president of water protection for Save the Sound. “If we do not act, climate change impacts—including rising water temperatures and changes in storm frequency and intensity in the Sound—threaten to erase our hard-won gains.” ■

Save the Sound works across the Long Island Sound region to protect the Sound and its rivers, fight climate change, save endangered lands, and work with nature to restore ecosystems. More info at savethesound.org.