Water sample MR-0.24 starts its journey at a precise set of coordinates on New York’s Mamaroneck River. © SavetheSound.org

Over the 12 weeks of its 2023 bacteria monitoring season, Save the Sound collected roughly 780 water samples from 60+ sites along the western Long Island Sound. Every sample was analyzed in the John and Daria Barry Foundation Water Quality Lab in the organization’s Larchmon, NY office. Results were published weekly at savethesound.org.

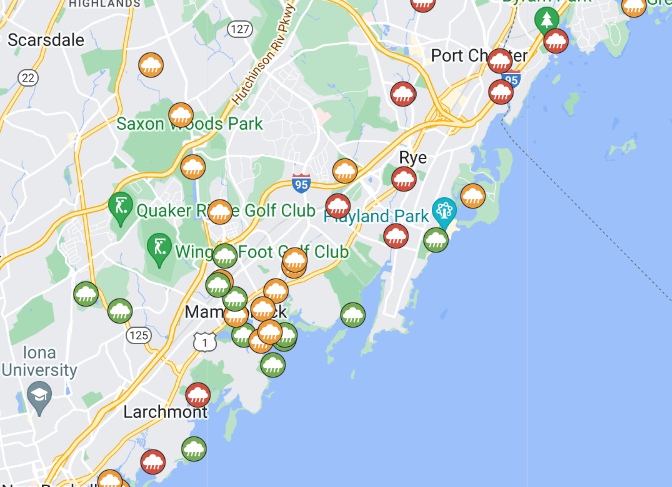

As with many journeys, this one ends with a dot on a map. Not a destination, in this case, but a designation. A green dot means all is well. Orange is a failure. Red dots are significant fails. When it comes to the journey of a water sample, you want to end up with a green dot.

The journey for what would become MR-0.24 began as water, flowing down the Mamaroneck River in the morning sun on Wednesday, August 9. A quarter-mile from Long Island Sound, it would be intercepted by Scarlett Crakes.

9:32 a.m.: Scarlett’s journey began in a supply room two miles away, where she pulled an orange folder from a plastic bin. Inside was a data sheet noting the four locations Scarlett would be responsible for sampling this day. The fourth was a spot off Phillips Park Road on the Mamaroneck River, designated MR-0.24. Scarlett, a summer water quality intern, gathered an extendable pole with an eight-prong claw, a cooler bag, and a baggie containing blue rubber gloves and plastic specimen bottles.

11:30 a.m.: Scarlett arrived at the bend in a path indicated by her info sheet: Longitude 73.732721, Latitude 40.951338. She removed the seal on the sample bottle, unscrewed the cap, then placed the bottle in the claw’s grip. Scarlett extended the Go Go Gadget-style pole to reach the river from a safe spot on the bank, pivoted the bottle’s mouth toward the oncoming current, and dipped it into the Mamaroneck River.

11:31 a.m.: 100 milliliters of water whose journey that morning had begun somewhere upstream were captured. Water Sample MR-0.24 had been secured.

1:54 p.m.: Work stations covered every available inch of countertop in the lab. Pouches were laid out in rows, each labeled to match a sampling site. The one awaiting MR-0.24 was sixth from the left, alongside other freshwater samples.

1:58 p.m.: Scarlett retrieved MR-0.24 from a refrigerator and placed it in its station, next to another plastic bottle containing 90 mL of pure water. A packaged pipette was placed next to a small packet of Colilert-18, a culture to help detect E. coli.

2:07 p.m.: Gloved up again, she removed the pipette, attached it to a pump handle, then placed it into the sample bottle. She drew 10 mL of MR-0.24, then expressed it into the pure water and poured in the Colilert-18, the particles sinking like flakes of fish food. Next, Scarlett took the mixture in her left hand and shook it 25 times.

2:24 p.m.: Scarlett poured the MR-0.24 concoction into its pouch, one side covered with foil, the other a panel of clear wells – a big one the size of a takeout ketchup packet, 48 square thumbnail-sized windows, 48 tiny ones. This pouch was placed into a rubber mold and slid into a sealer, forcing the treated water into the wells and securing everything in place.

2:28 p.m.: Scarlett stacked the samples and placed them inside an incubator set to 35 degrees Celsius (95 Fahrenheit). E. coli needs to cook for 18 to 22 hours.

Thursday, Aug. 10, 10:38 a.m.: MR-0.24 spent 20 hours, 10 minutes incubating until Heather Leonard, another water quality intern, removed it for scoring. The water in every window glowed butterscotch yellow, as expected (Colilert-18 feeds a variety of bacteria). Heather placed MR-0.24 in the chamber of the fluorescence analysis cabinet and viewed it under UV light, marking every cell fluorescing white with a black Sharpie. Those wells were contaminated with E. coli.

10:44 a.m.: Heather counted the slashes: three among the small wells, 15 among the large. She consulted the IDEZZ Quanti-Tray/2000 MPN Table, did a quick calculation, and came up with the score for MR-0.24: 211. For a freshwater sample to pass, the Most Probable Number of colony-forming bacteria per 100mL of water must be lower than 235.

MR-0.24 passed.

It had passed the previous week, but it had failed each of the first seven weeks of the season, and it failed the three weeks after. But on that day, at that time, at that spot, those 3.4 ounces fished out of the Mamaroneck River were safe for people and pets to interact with. When the map of Week 9 results was published, MR-0.24 was depicted with a green dot. A happy ending. To learn more, log onto SavetheSound.org. ■