By John Rousmaniere

Here’s a challenge: Sail 635 miles almost entirely out of sight of land, crossing a current running up to six knots in any direction, and then make your landfall on a low, tiny island that’s guarded by a sharp-edged reef.

Here’s a challenge: Sail 635 miles almost entirely out of sight of land, crossing a current running up to six knots in any direction, and then make your landfall on a low, tiny island that’s guarded by a sharp-edged reef.

It’s a safe bet that every navigator on these boats starting the 2014 Newport Bermuda Race studied up on the Gulf Stream and weather. © Talbot Wilson

Did we mention that you’re navigating a race to Bermuda? The vital importance of navigation to the Newport Bermuda Race is reflected in eight prizes that are either presented to the navigators of winning boats, or that include sextants as decorative features.

Did we also mention this? During the first 70 years of the Bermuda Race after it was founded in 1906, navigators had to rely on one instrument: the sextant. Some boats had radio direction finders and other primitive electronics, but the one essential navigational tool was the sextant. You know how important navigators are because they’re often the butts of jokes. A Bermuda racer, Edward Streeter, described the typical navigator as “crawling from the main hatch like a strange, subterranean animal. With eyes red and bleary from peeking through a sextant all the afternoon, he examined the sky critically and then dove below for his instruments.” Back on deck, he handed a stopwatch to the designated timekeeper, took sextant sights of the sun or a star, and slid back below to calculate the fix using thick printed tables and a special clock, called the chronometer.

All that labor led to the moment of truth, which (according to experienced navigator Nick Nicholson) concerns “that little speck of land in the middle of the ocean.” Nicholson added, “All the self-doubts about what you had done for the last three or four days piled up at once. Were my sights accurate? Do I really have a clue? The first time Bermuda popped up in front of the boat approximately when and where it was supposed to be, it was a divine revelation. There was meaning to the universe. The celestial clock was still God’s timepiece, and it still ran with eternal perfection.”

All that labor led to the moment of truth, which (according to experienced navigator Nick Nicholson) concerns “that little speck of land in the middle of the ocean.” Nicholson added, “All the self-doubts about what you had done for the last three or four days piled up at once. Were my sights accurate? Do I really have a clue? The first time Bermuda popped up in front of the boat approximately when and where it was supposed to be, it was a divine revelation. There was meaning to the universe. The celestial clock was still God’s timepiece, and it still ran with eternal perfection.”

No object says “navigation” quite like a sextant. This is the William L. Glenn Family Participation Prize, awarded to the top family-crewed boat in the Newport Bermuda Race. © Scott King

In sextant days, a navigator’s word was Scripture. “The navigator was like a priest,” says Larry Glenn, who has guided boats in “the thrash to the Onion Patch” for decades. “People were always asking, ‘Where are we?’, and when you blindly put your finger on the chart, they’d believe you and say, ‘Ahhh,’ in a respectful way.”

True, a navigator might not know the boat’s exact position. Glenn says, “Someone would ask you, ‘Where are we?’ and you’d have to say, ‘I don’t know,’ and then he’d say, ‘Well, I’m going to sleep with my feet forward in case we run into the reef.’” If the reef has stopped only one boat in Bermuda Race history, it’s because navigators are cautious and also ingenious. At least one navigator followed a cruise ship to the island. A few have claimed that they followed the scent of oleanders and other island flowers blowing down to them.

The Age of the Sextant ended in the 1970s. After a big scare in a storm in 1972, the Bermuda Race permitted new Loran-C instruments within 50 miles of the start and finish. In 1980, electronics were permitted from start to finish.

The Age of the Sextant ended in the 1970s. After a big scare in a storm in 1972, the Bermuda Race permitted new Loran-C instruments within 50 miles of the start and finish. In 1980, electronics were permitted from start to finish.

Robbie Doyle, aboard Shockwave, won the 2014 Schooner Mistress Award as Navigator of the first boat to finish. © Stephen Clotier/PhotoGroup.us

When Loran and, later, GPS proved to be remarkably precise, many navigators were tempted to throw out old disciplines, like keeping a dead-reckoning plot—tracking the boat’s position on the chart based on her course and speed.

One of the many true believers in the DR was Jim Mertz, who navigated boats in 17 Bermuda Races and sailed in a record 30. “Once, we had a Loran expert on board and didn’t keep up the DR. When we got near Bermuda the Loran coverage ended. I learned two things from this experience. Number one, keep up the DR. Number two, don’t let the navigator stand watch. It takes a lot of energy to keep up a DR.”

Navigation became tactical in the 1980s when electronic precision and the Gulf Stream analysis of Jennifer Clark and other oceanographers came together to make it easier to find favorable in and near the Gulf Stream. Good navigators also relied on their senses. In the 1982 race, the famous sloop Carina was aimed almost at Bermuda when skipper Richard Nye poked his head up through the companionway took a look around. Way up to windward, a lightning bolt flashed down to the water.

“Tack,” Nye ordered. The crew looked at him incredulously. Someone told him they were only 10 degrees off the layline to the island. “Tack! There’s lightning to windward. There’s warm water up there. The Stream’s up there.” Carina sailed on the “wrong” tack until she was well into hot water, came about, and with a 3-knot current boost, charged toward Bermuda at over 10 knots over the bottom. She won her division and almost the race.

Today, tactical navigation is understood better than ever. To quote oceanographer Frank Bohlen, writing in the 2012 Bermuda Race program: “For the Newport Bermuda racer, the point at which the Gulf Stream is encountered is often considered a juncture as important as the start or finish of the race itself. The location, structure, and variability of this major ocean current and its effects all present a particular challenge for every navigator and tactician.”

Today, tactical navigation is understood better than ever. To quote oceanographer Frank Bohlen, writing in the 2012 Bermuda Race program: “For the Newport Bermuda racer, the point at which the Gulf Stream is encountered is often considered a juncture as important as the start or finish of the race itself. The location, structure, and variability of this major ocean current and its effects all present a particular challenge for every navigator and tactician.”

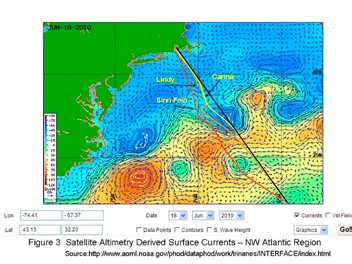

This analysis of the Gulf Stream uses an altimetry model showing current and water temperature. Many other visual images are available online.

I can’t predict who will win the 50th Bermuda Race next year. But I can say for certain that long before the race starts on June 17, 2016, the typical navigator will spend hours studying charts of the Gulf Stream and Bermuda. Articles and much more about weather, the Gulf Stream, and tactical navigation can be found on BermudaRace.com at the Commentary button and the Resources tab.

The author of The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, Fastnet, Force 10, and other books on seamanship, John Rousmaniere also wrote the Bermuda Race’s history, A Berth to Bermuda.

4

Safety at Sea Seminar Weekend is March 19 & 20, 2016

To be eligible for the Newport Bermuda Race, at least 30% of a yacht’s crew (including the Captain and the Navigator or a Watch Captain) must have completed a US Sailing sanctioned Safety At Sea (SAS) seminar within the last five years prior to the race’s start. In order to meet the needs of participants, the Cruising Club of America is hosting a Safety at Sea seminar weekend on March 19 & 20, 2016 at the Marriott Hotel in Newport, RI.

As a US Sailing sanctioned seminar, it satisfies the requirements of most US-originated nearshore and ocean races and offers an ISAF certificate as an option. The seminar follows the curriculum provided by ISAF Offshore Special Regulations, with topics of interest to both racing and cruising sailors. Certificates earned are issued through US Sailing and valid for five years. The moderator will be Bruce Brown, who has experience in moderating SAS seminars and Practical hands-on training seminars. The ISAF training will include both a refresher option and a second day of Practical hands-on.

In addition to the SAS and ISAF options, the organizers will offer a Race Preparation seminar on Sunday, specifically oriented to those participating in the Newport Bermuda Race with topics including class structure and prizes, developing a prerace strategy, the Gulf Stream, preparing the boat, sail selection and Q&A. A Sunday medical seminar will include a presentation on medical assessment and an opportunity to address some likely medical scenarios. The race preparation and medical seminars will be available as separate and stand-alone seminars for those who do not require SAS or ISAF certification. For more information, contact Leslie & Garry Schneider at SafetySeminar@cruisingclub.org, or visit bermudarace.com.