By David Seigerman, clean water communications specialist

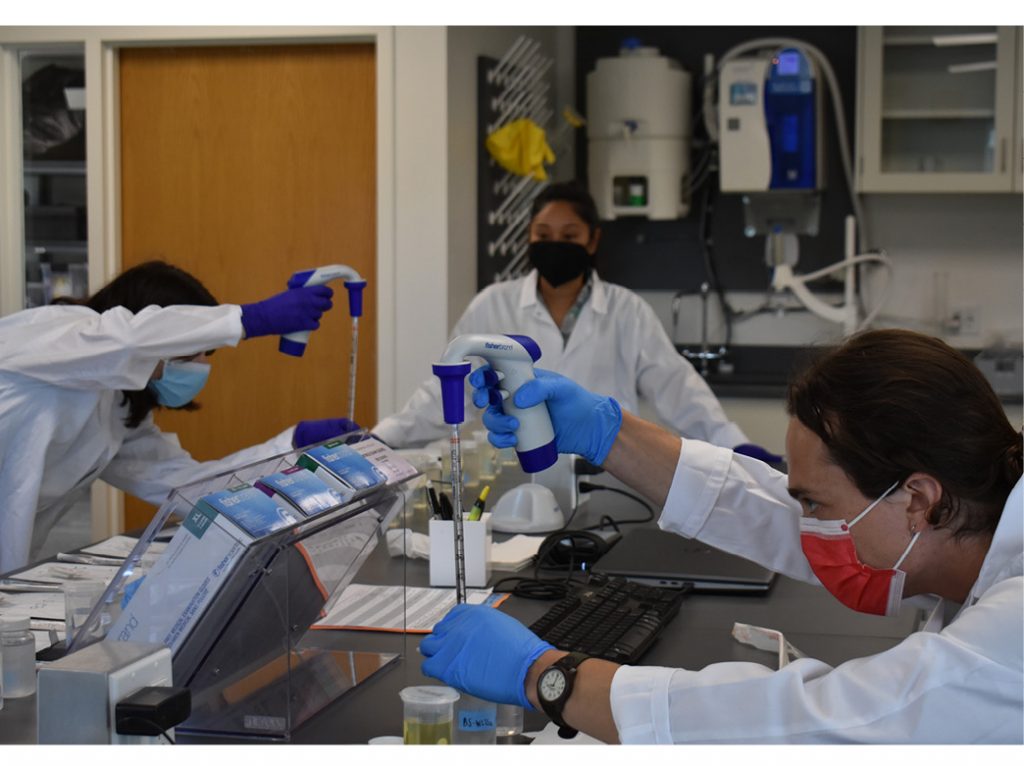

At work in Save the Sound’s new John and Daria Barry Foundation Water Quality Lab are (left to right) seasonal water quality intern Bernadette Russo, Environmental Analyst II Elena Colòn, and seasonal water quality intern Nathaniel Goetz. © savethesound.org

At its ribbon cutting back in April, the John and Daria Barry Foundation Water Quality Lab gleamed with possibility. But like a racehorse in a stall or boat tucked safely in its slip, some things can’t fully be appreciated while they are at rest.

This summer, Save the Sound’s new lab facility—the state-of-the-art centerpiece of our new office space in Larchmont, NY—is humming with activity, alive not only with possibility but with work. Important work, which is why its construction is such a watershed development for Save the Sound, our partners and supporters.

“The quality of the Sound is a core part of our family’s childhood and adult experiences, which we share with countless families up and down the Connecticut and New York coasts,” said James Barry, a volunteer for Sailors for the Sea powered by Oceana, a competitive sailor, and one of John and Daria’s five children. “A focus on research that can not only help the long-term sustainability of the Sound but hopefully provide information to support water quality in other areas is a clear priority in our mind.”

The lab is full-speed ahead gathering critical water quality data, running tests on samples for two annual programs. There’s the seasonal Fecal Indicator Bacteria monitoring, in which technicians measure levels of Enterococci, E. coli, and other fecal indicator bacteria from more than 60 monitoring sites in western Long Island Sound (specifically, Greenwich, CT, Westchester County, and Queens, NY). And, for the first time since it was launched in 2017, the chlorophyll-a samples from the Unified Water Study—collected by 26 partner groups from 44 sites around the Sound—can be processed in-house. Nitrogen and phosphorous samples are set to be phased in for the 2023 season.

“Rather than send thousands of samples out to external labs, we’ll be able to have more control and be more efficient when we process them at our lab,” said Peter Linderoth, director of water quality for Save the Sound and the UWS project manager.

“The exciting thing is now that we have the new lab, there’s room to expand in the future, to do other types of analyses and tests,” said Elena Colón, Environmental Analyst II, who manages the workflow in the lab. “Coastal acidification is one of them. We could finally participate in that in a more meaningful way and produce that data.”

Linderoth sees several additional growth opportunities for his team, thanks to their new home base. One potential prospect is monitoring harmful algal blooms, which he considers an emerging threat to Long Island Sound. “They become more prevalent as waters warm in addition to other changes associated with climate change,” Linderoth said. “There’s excess nitrogen entering Long Island Sound that can fuel these blooms. We will be positioned to collect and process samples from all reaches of the Sound and monitor the westernmost portion that is not always a main focus for this type of effort.”

The new expanded lab also provides for an expanded educational component. Colón envisions more opportunities for volunteers and students to gain valuable experience working in the lab. Back in the spring, Save the Sound water quality advocate Sam Marquand launched a program with the Boys & Girls Club of Mount Vernon. Nine students began their training in the lab, preparing to go into the field this summer to collect data from a stretch of the Hutchinson River.

“It’s interesting for them to get a sense of what our focus is in an area like Mount Vernon, who we are, what we do, and how we can work together to start tackling some of the environmental injustices affecting their community,” Marquand said.

One promising down-the-road opportunity that Linderoth sees is DNA microbial source tracking, adding clarity to fecal bacteria monitoring. Right now, the water quality monitoring helps identify places where there are high levels of fecal indicator bacteria in the water, making certain areas unsafe in regard to human health. The current testing procedures, though, are unable to determine the source of that fecal contamination, whether it’s geese or dogs or raccoons or people.

“It’s a public health issue,” he said. “We are poised to expand the lab to do DNA processing, and check genetic markers to see if there is human waste in the water that can make people sick.” Colón added, “Our whole goal is to produce data, and then take action on it.”

From now on, many first steps of our actions to preserve and restore Long Island Sound will be taken inside the John and Daria Barry Foundation Water Quality Lab. Learn more about Save the Sound’s water quality work and more at savethesound.org. ■