By R.J. Rubadeau, Cruising Club of America Boston Station

My formative sailing years were spent on a short list of state-of-the-art sailboats in major ocean races along the Eastern Seaboard when Nixon was president. My journey to becoming a professional offshore sailor began with an 8,000-mile Pacific Ocean crossing from Sydney to San Diego as captain of the Maxi Ondine. This life-forming event crystalized my core belief that those scalawags you are lucky enough by design or chance to sail with are a huge magical perk of this calling. Paying close attention to the nuances of crew dynamics ensures likely success on your way to becoming a better captain.

The evolution of an offshore captain is a confusing journey with a chart full of hidden reefs and bad advice. Leadership demands searching for that hard-to-find open space between long-held opinions among mismatched strangers where reason, humor, or candor can slip in. Tempers create unreliable shipmates. Coping with people aboard in critical situations is alchemy, not science. A prime rule to remember is that heated words often mean the most and speak the loudest after the voyage ends.

It was Christmas. Wait … I should clarify that odd observation and fill in the blanks. It was four days before Boxing Day in 1973. The true bluebloods of the offshore racing scene, the uber-wealthy and colorful few, were gathered with their trophy crews and high-tech machines at the docks of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia. Mary and I were finishing a year teaching school in Sydney, and I was hoping to score a ride aboard a visiting yacht returning stateside.

The docks were full of likely suspects. Everyone was moving at high speed in that semi-controlled state of panic days before a major ocean race. Ondine, scratch boat and queen of the fleet, was easy to spot from a distance. Her two matched spars towered over the rest. Her baby-blue hull seemed as massive and flat as an aircraft carrier; the winches were the size of truck tires. I gawked.

“Captain aboard?” I asked a giant of a Kiwi rebuilding a winch.

“You American?”

“As apple pie.”

“The captain will definitely want to see you. Tell him Mark sent you.” The black, scrub-brush hair jerked in the direction of the bar. This was a completely unexpected turn of events. Mark later told me he thought I was someone else.

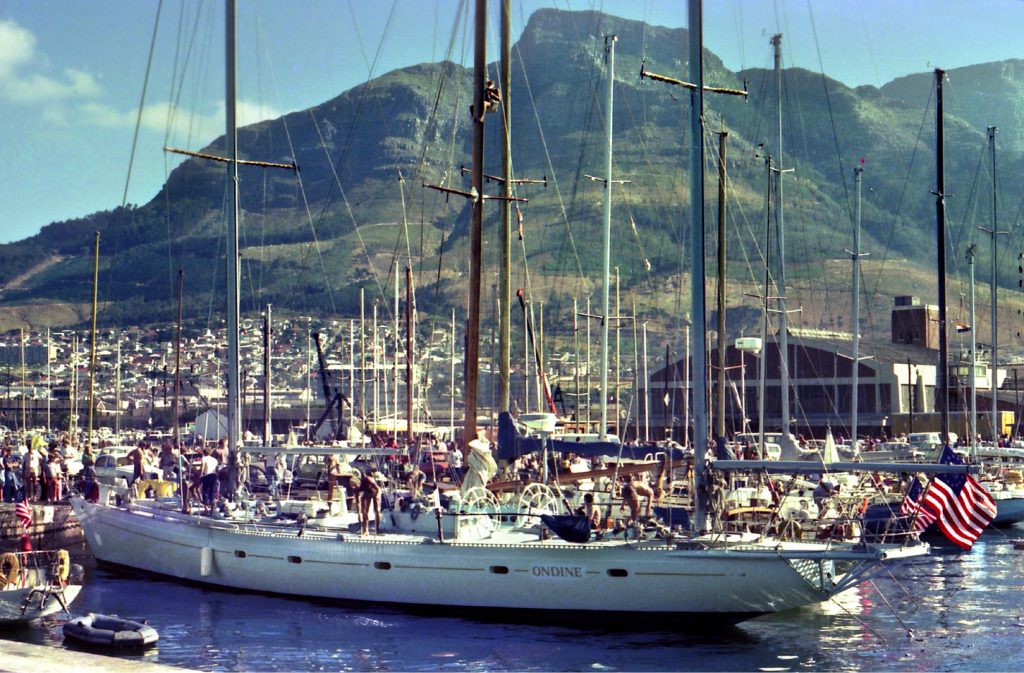

Ondine in full race prep at CYCA in Sydney

Thom Richardson was standing at the bar. He was tall, tan, rail thin, and blond. He looked like a movie star (maybe Stewart Granger from the ‘30s), visibly British, very upper crust. Looking down his nose at someone looked swell on him. His face had been all over Rupert Murdoch’s tabloids for days; they dubbed him the most eligible bachelor ever — and he was stuck Down Under through Christmas.

Ondine leads the fleet down Sydney Harbor.

I went over my pitch about my racing creds, dropped names, and injected the right touch of competent humility on my maturing but nascent offshore sailing skills. The whole sell was, “Please, like me, I don’t bitch or whine, and I will pull my own weight and then some.”

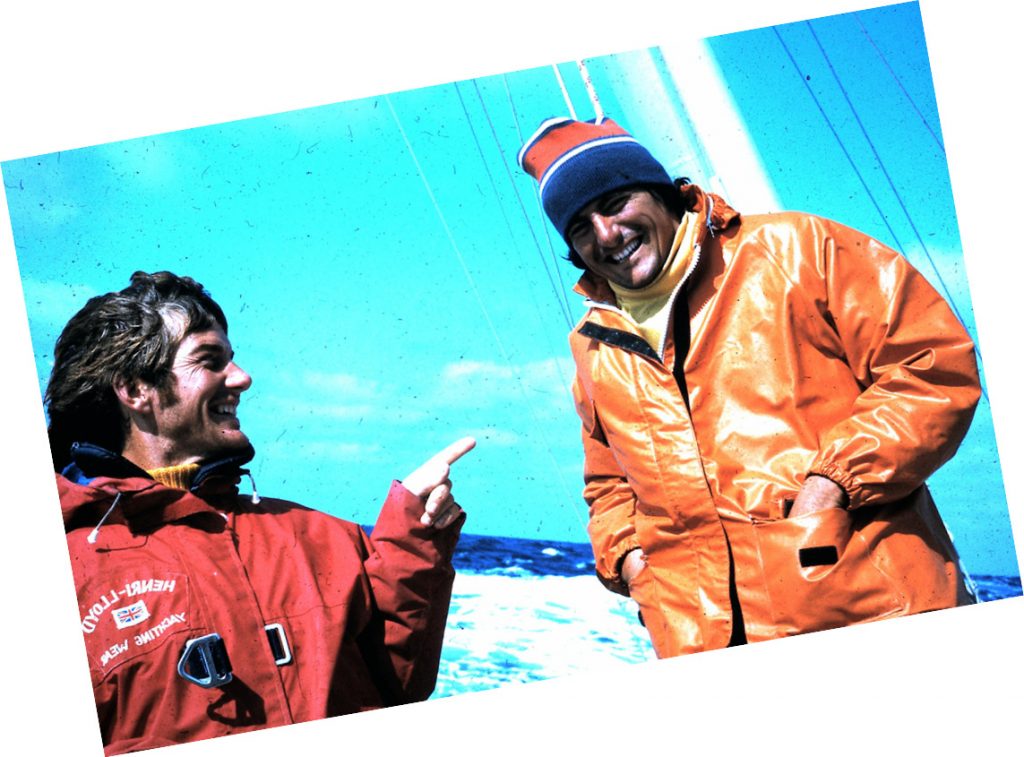

Captains Thom Richardson and Bob Rubadeau

“You are American — U.S. passport?” he asked.

I nodded.

“Current, like, you can go back anytime, right?”

My eyebrows went up in twin paradoxes, and I nodded

again. What gives here?

“Don’t really need an extra hand for the race, but we are

sailing for San Diego mid-January after we fit out in Kirribilli. You want to go?”

Unable to believe my good fortune, I was speechless. Thom frowned, waited, looked at the ceiling, and slowly growled in frustration.

“Okay, you can go on the race. But you got the forepeak and the sail-bag sandwich.”

I blinked, surprised again. Thom’s eyes dropped, and then he got serious.

“All right, no forepeak, but I can’t promise where you’ll dock.”

I gulped and turned slightly away because I felt faint with my good luck.

“Bloody hell.” His voice sank to a whisper in resignation. “Right you are. Go pick any bunk not occupied. I’ll square it with Huey.”

I was in a very fluid negotiation here, and I was scoring all the goals. I kept my mouth shut. I stuck out my hand, and we shook on the deal.

“You do speak English, right, mate?” Thom finally asked with a worried frown.

I bought my new boss a beer. I was basking in the glow of being taken for a real sailor without having to resort to a heavy sell, but the other shoe was about to fall on my runaway ego.

“Fact is, I got a dozen guys lined up for that berth, but none of the rotters is a damn Yank. Jones Act says a U.S.- flagged vessel must have a U.S. captain to clear into U.S. waters. Usually, you can’t have a yacht race without a full plague of ballbusting Americans. Now, I can’t find one. Don’t forget your bloody passport.”

The author steering in the Southern Ocean

To starboard was a nude beach.

“Steady as she goes there!” Thom bellowed. The crew waited at sloppy attention. The wind ripped a tattoo on the Stars and Bars at the stern. Ondine ran down Sydney Harbor with a bone in her teeth. The afternoon testing of the newly built light drifter had gone well, and now we were on a mission to press the race

gear for weaknesses while we were here in a major port where we could easily manage repairs.

“Lively now!” Thom said, putting into play a hastily sketched and embarrassing plan. “Preeee-sent to starboard!” The crew, four stout lads in gym shorts, scrambled shoulder to shoulder and straightened their chorus line along the starboard rail.

The boat was close-hauled, and I was at the lower steering station of the tandem wheels. Our girl was moving with determination. The water was barely 20 feet deep, and the boat needed 12 feet to stay afloat. These were those dark, medieval days long before the security of GPS plotters. We were so close to the beach I felt I could drag my fingers through the sand.

The multi-national crew looked solemn, nervous. I had barely gotten to them and couldn’t be sure they were enjoying the moment.

“Ready the volley, boyos.”

The rail dipped to a strong random gust, and all hands steadied themselves at the lifeline. Thom spotted the billboard identifying the clothes-optional beach section — a crossing between the haves and the have-nots.

“Smartly now,” he snapped. “Shed the togs!”

At the helm, I was caught by surprise to see five men suddenly bare themselves from the waist down, angling their considerable poundage of glutei maximi out over the rail. Shouts, whistles, and applause came downwind every time we flew by a group of beachgoers sprawled naked on towels and blankets.

Having been left out of the planning for this drive-by mooning, I was now in a quandary. I needed both hands to keep this overloaded beast from rounding up and heading for the beach, but how could I be the only one not inflicting himself to the humiliation of showing private parts unasked? I reached down and began to tug at the rope belt I had put through the loops of my old cutoff jeans that morning. Instead of a tidy and easily loosened square knot, I had laid the final overhand wrong and ended up with a tight, wet “granny.”

I struggled to keep one eye on the depth and the other out ahead where bobbing heads of swimmers randomly appeared. I slalomed past obstacles as my comrades’ grins slowly began to lose their luster — it was a long beach.

The ranks broke in full rout. The crew stampeded back to the cockpit. Their sideways glances and winks served notice that I was still a highly unknown commodity. Failing to drop my own pants was not team-building behavior. The crew wandered to the windward winches to bring us on to the other tack.

“Ready about, hard over.”

Everyone moved at Thom’s order, but no one jumped to take the wheel from my hands as I put the 73-foot Maxi through the eye of the wind and lined up on the vaulted “white sails” of the recently built opera house way down the harbor below the green lawns of King’s Park.

“Marking!” I called out.

The tall masts groaned like prod-shocked mules as the crew set up the sheets. She was stretching out fine. Eleven knots easy.

“Marking!” I shared the visual course towards home. Nick, Thom’s younger brother, finished at the port sheet “organ-grinder” with a flurry of double-armed spins, then slapped me on the back, and disappeared below. Once the mainsheet had joined suit, the rest of the crew ducked out of sight. Thom gave me one long quizzical look. Turning to the hatch, he said, “You alright, mate?”

“What are you going to tell the press gang when they ask about the moons over Sydney? I saw lots of cameras,” I said.

A dark cloud moved across his movie-star face, then he smiled. “Bloody hell, you’re the damn captain, figure it out,” he said, and he disappeared below.

Looks like I was finding my odd place in this pecking order.

Ondine took line honors and the trophy in the Sydney Hobart Race, then went on to cross the Tasman Sea and leave New Zealand behind. Two hundred miles east from the South Island, we were now locked into a tough battle with Neptune. Our current gale-strength weather front was just the latest pachyderm in a long line of trunk-to-tail monstrous depressions that were parading along our course.

Ondine’s victory made the news at Hobart.

I stumbled out of sleep after a four-hour bunk-induced coma and fumbled into my dripping foul-weather gear. Nearly every piece of clothing I had aboard was on my body as molding insulation. I tucked a wet but not yet dripping towel around my neck and zipped the jacket up tight before snugging the hood over my heavy wool cap.

I read the last watch entry in the logbook, made exactly an hour earlier: wind speed, 38 to 47 knots; wave height, 25 to 35 feet; breaking waves; storm staysail amidships; speed, 8.5 to 15.1; course, 110 to 165 degrees; temperature, 46 degrees F. The terrifying entries were scratched in shaky capital letters. It had been bad on my last watch. It was now a lot worse.

I paused at the hatch and listened to the chaos outside, trying to hear above the keening wind for the rush of water along the scuppers. I didn’t want to invite a few tons of Southern Ocean into the cabin as I scrambled on deck. The boat’s movement had no rhythm. Thrown this way and that, the 50-ton boat was skidding along in a ponderous wobble, suddenly lurching past 45 degrees from vertical before slowly regaining her feet. I slid the hatch open over my head.

The sea was moving like a boiling vat of black tar. A figure manned each wheel, struggling in tandem to keep the boat under control. I quickly pulled myself over the washboards with all the grace of an elephant seal. I snapped on my shackle to the heavy wire jackline and cowered under the dodger. One of the two figures moved in my direction.

“Hate to leave all the fun,” Athol shouted in my ear. “I’ll let you have some of the sweetness for a mite, mate.”

“A kind Kiwi gesture,” I yelled above the wind.

“Better hurry,” he warned hoarsely. “And hold on.”

He pressed a second safety harness and tether into my hands and was gone below before I could ask why. On leaving the shelter of the hard dodger, I made the simple lifesaving mistake of turning to look forward.

Fifty-something years later, my neck hairs still bristle at the memory of that biblical doomsday scene. A 25-foot wall of water is imposing in the extreme, and to confront it 1,000 miles from land adds steroids to the fear level. If you ever have the misfortune to be heading down the face of a wave while rapidly overtaking the one ahead, you’ll find that the perceived height of the monster in your way easily doubles in size.

I dropped back under the dodger, wedging myself in tight.

I looked up and saw Mark, the first mate and helmsman, dis- appear under a solid sheet of spray. I quickly pulled my arms through the heavy web strapping of the second safety harness and secured it tight across my chest.

When most of the water had tumbled over the stern, I moved aft as fast as my Michelin Man outfit would let me. I followed Mark’s lead, and as soon as I could grab the wheel, I snapped my two tethers into the stout D-rings on both sides of the pedestal. Mark wiggled his eyebrows like Groucho Marx. I was worried; farce wasn’t a usual part of his antics. What was so funny?

Approaching Pitcairn

Anchored in the lee of Pitcairn

I learned about gallows’ humor while riding the razor’s edge of disaster for the next two hours. The cycle would begin in the windless trough between two mountains of moving water, where the boat would shake itself like a spaniel at a pond’s edge. Hearing the approaching waterfall high behind us, Mark and I would tug away at each other’s best guess on where to position the rudder for the next big surge. The tandem wheels would spin free from our wet hands as we struggled to keep the bow straight downhill. To be off by 10 degrees meant the boat might be thrown sideways with little steerage or control and the next wave could roll us over as easily as a bathtub toy. We needed speed.

Suddenly, with enough force to buckle our knees, the stern would climb onto the wave like an express elevator, then the bow would plunge at an increasingly steep angle. Gale-force winds would swarm over the stern counter, finding and pushing anything vertical, including our exposed backsides. The boat would be pushed over nearly 40 degrees and accelerate with a neck-snapping lurch. She’d gain speed recklessly and race the wave face like a racehorse in the final furlong.

Surfing may be fun on a small boogey board on a sunny day at a Nantucket beach, but this was brutal. Outpacing the wave, Ondine would use her keel and surf across the steep face. Soon the wave behind us would be at our stern, blocking the wind, and our speed would plummet. The water under the keel would go slack, and we’d lose grip with the rudder. We’d surge along the crest of a three-story canyon, teetering on a crumbling wave with no steerage. Then things would get interesting.

We’d heel over to the fierce wind and begin to hit 12, 13, 14 knots and plunge downhill, catching up to the wave ahead. It would look as if a solid wall of ocean was suddenly reversing course and coming back at us. The bow would slam into the hillside and bury itself a dozen feet into black water. Mark and I would be slammed forward, our chests smacking the wheels as the boat went from careening in the mid-teens to the low single digits in a split second.

Ondine would literally stop dead, lift her bow, and scoop a three-foot-high wave along the decks. I remember thinking how strange to see each safety-line stanchion leaving a bow wake in the frothing cauldron. We’d hold on for dear life as the cold water poured off the stern and tried to take us with it, then check to see if each other was still standing. Ondine would shake herself like a happy puppy, and the next wave would begin to lift our stern again. Two hours of this and an another four spent cowering in my bunk quickly wore down my enthusiasm.

We made 1,000 miles of easting during the first four days of our passage and only barely crossed the 50th parallel of south latitude into the Furious Fifties. When the weather showed signs of getting even worse, we had a brief crew meeting and decided to turn north towards the equator, and leave the Drake Passage and Cape Horn until another day. It would be 32 years before I’d get back and scale the “Everest Horizontal,” and I wasn’t disappointed with the spoiled soup of fine weather that time either.

Ondine was nineteen days and 3,000 nautical miles from New Zealand when we thought we might be close to our needle in the haystack — Pitcairn Island. The smart money in the crew’s betting pool was not on when, but if we would sight Pitcairn. One shipmate wondered if we would sight any land ever again (and he was one of the three of us sextant navigators). After dinner one starry night, I calmly predicted that we’d see our goal the next day at breakfast. I don’t think the crew stopped laughing out loud until dawn when the morning watch looked astern and spotted a humped smudge just about to vanish below the horizon. We turned around and made our way to the descendants of the Bounty mutineers.

Four generations of smiling new friends were seated in the wooden lifeboat tethered alongside Ondine. A gap-toothed young teen smacked his hand under his armpit, imitating my energetic attempts at grass-skirt hula dancing at a sweet-16 birthday party the night before. Everyone had called me the “captain and mailman who shouldn’t dance.” The entire population of the island, all forty-eight souls, had joined together in the fun.

Just thirty hours ago, when we’d arrived at Pitcairn Island bearing a precious satchel of mail from Auckland, we were strangers. Now we bantered like family. Shocks of bright, unruly red hair riding over freckles were scattered among the happy Polynesian faces, a testament to the diversity of these descendants of the original Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian mentors.

One man’s voice silenced the chatter of goodbyes with a melody. When he reached the chorus, the entire congregation joined in and followed him in an up-tempo round. The sweet voices of women, men, and children chased each other through the verses of In the Sweet By and By, a centuries-old song shared aboard ships embarking on the dangerous sea. Delivered in the strong voices of an ancient seafaring clan thriving on a lonely rock a thousand ocean miles from the nearest land mass, the song welded to my soul. The fact that Ondine’s crew had nearly 5,000 open ocean miles to reach Acapulco, where Mary would join us for the last leg to San Diego, loomed large. The tempo changed once again as the song came to a close:

Now one last song we’ll sing

Goodbye, Goodbye

Time moves on rapid wings

Goodbye, Goodbye, Goodbye

We part, but hope to meet again

Goodbye, Goodbye, Goodbye …

It was now up to the old uneasy partnership between sailors and the gods of the sea to ensure that we all stick around to be part of the next chorus to be sung somewhere over the horizon. No one spoke or looked anyone in the eye for a long while. We scurried about the deck, carrying our emotions proudly, like a peacock-feather hat, as we got underway. The running backstay finally took up the strain on the rig like a violin string, and the double-reefed main turned us downwind.

In hindsight, this shared goodbye ritual taught me how to become part of a new crew. Hugging life’s important lessons when they appear is the surest pathway to being a better captain. ■

R. J. Rubadeau is an award-winning author, columnist, journalist, and poet. His career and adventures as a professional blue-water sailor have been chronicled for over four decades in the world’s leading sailing periodicals. Bound For Roque Island: Sailing Maine and the World and Bound for Cape Horn: Skills for Expedition Cruising have both won numerous awards for nonfiction books and nautical memoirs. Rubadeau lives with his wife, Mary, and a posse of grandkids, dogs, and horses near Durango, Colorado. Each summer, Dog Star, the family’s 93-year-old Phil Rhodes-designed ketch, plies the cold, clear waters of New England and beyond, crewed by cherished hardcore friends and four generations of this seafaring family.

With thanks to the Cruising Club of America in whose magazine, Voyages Issue 66 this article first appeared, and Voyages editors Amelia & Robert Green.

The Cruising Club of America (CCA) is a collection of 1,400 ocean sailors with extensive offshore seamanship, command experience, and a shared passion for making adventurous use of the seas. Their experiences and expertise make them, collectively, one of the most reliable sources of information on offshore sailing. Visit cruisingclub.org to learn more.