By Joe Cooper

Jill and I travelled to New York City before the holidays to visit with a mate of ours from Oz. Nina is the younger daughter of one of my great mentors, Tony James, the Finn sailor I wrote about a while back (www.windcheckmagazine.com/article/the_finn_dinghy_the_olympic_singlehander/), and she was in town for business. We met at the Museum of Modern Art and spent an hour wandering the museum’s fascinating galleries and catching up. We had Good Gossip about the uncles & aunts, nieces & nephews, her sister, the eccentricities of her parents—legendary amongst their circle of friends—the political scene in both countries, the bush fires, and what she, and we, were doing workwise. Escaping from the relative peace and sanctuary of Aquidneck Is., Rhode Island, to the vastness and humanity of NYC in the Christmas season, and jumping right into the eclectic world of Modern Art was a bit of a trip in the Tardis, from our living in the city days.

The spectrum of creativity on display in this museum reminds us of the variants of The Human Condition. There were ‘regular’ art pieces, drawings, and paintings, those images, the media really, most commonly thought of as Art. New York being New York and in a museum named Modern Art, there was a broad range of ‘other art’ works on display, and, in a couple of cases, in action. The museum has many gallery spaces, each of which seemed to be dedicated to a particular artist or theme.

A little-known piece of Cooper history trivia is that my father was an artist. Many, perhaps most, of my founding childhood memories, all connected with sailing, were voyaging with Dad on a series of small boats that he used as a mobile studio for his painting and aboard which we covered the estuaries and bays on a body of water 25 miles north of Sydney called Broken Bay.

We would haul into a cove, beach, creek or bay that were, for the most part empty, drop the hook, and within minutes I was off sailing in my Sabot and Dad was propped up in a corner of the cockpit. His usual MO was a cigarette, carefully rolled from tobacco, Champion Ruby by name, sold in a yellow pouch, rather the proportions of a kid’s fabric pencil holder, maybe five or six inches long by two and a bit inches wide. The resulting cigarette was mounted in a 4-inch-long tortoise shell colored holder and ignited by a match from the box he kept in the pouch. He had a sketch book before him, held to a piece of board he had fabricated for the purpose by what Australians know as a bulldog clip, a supply of pencils and a glass of scotch within arm’s reach, gazing out across the water to whatever it was that caught his eye.

I would be banging around in the Sabot, sailing up into my own creeks and indents, stepping ashore onto tiny beaches, pulling the centerboard up when I encountered shoal water, thankfully, for the wooden centerboard, invariably soft mud. If there was no wind in the sheltered blips of shoreline that were his favorite bolt holes, I would row. The mast was a proper mast with stays and a halyard, so I could simply lower the sail into the boat. I’d remove the boom off the gooseneck, extract the centerboard and lash the tiller amidships and continue exploring under oars.

The pair of us would, in our respective conditions, spend some number of hours, right up to dusk engrossed in our own worlds. The whole scene was one of peace, beauty, calm. Often the stillness would offer up, along the shoreline, a kind of twofer. There were the actual trees, rocks, mud, and sand strips, and the reflections of them, particularly late in the day when the wind would peter out and the landscape would reflect into the seascape, interrupted occasionally by a jumping, and flopping, fish.

These boats of his were very simple. None of the amenities we think of as necessary to our enjoyment of sailing today, extensions of our houses. Yes, it was basically camping on the water, but the memories are as strong today as the day after each voyage. Dad kept logs, diaries really of each trip, sadly lost now, but in which he recorded, in his elegant, artist script, curving along the lines of the hardbound book that was The Ship’s Log and using his Parker fountain pen, with blue ink and a medium nib, both the venue and his notes on the work and the nautical particulars of our passage. Life aboard is memorialized by these visions and the smells.

Deep, dank, thick, clinging eternal mud, salt air, kerosene Primus stoves, hurricane lamps, and Pliers Toast. This piece of Gourmet Camping was composed by the act of using the ship’s pliers to nip a piece of bread by a corner and drape it briefly over the flame of the Primus stove. The result was a slice of bread, just warm enough to melt the butter—kept in a plastic box and stowed in the bilge, the coolest place aboard—yet slightly brown and slightly crispy on the outside surfaces. A dab of jam on top and one had a snack worthy of, likely superior to, the most gastronomic café on a chic Parisian boulevard.

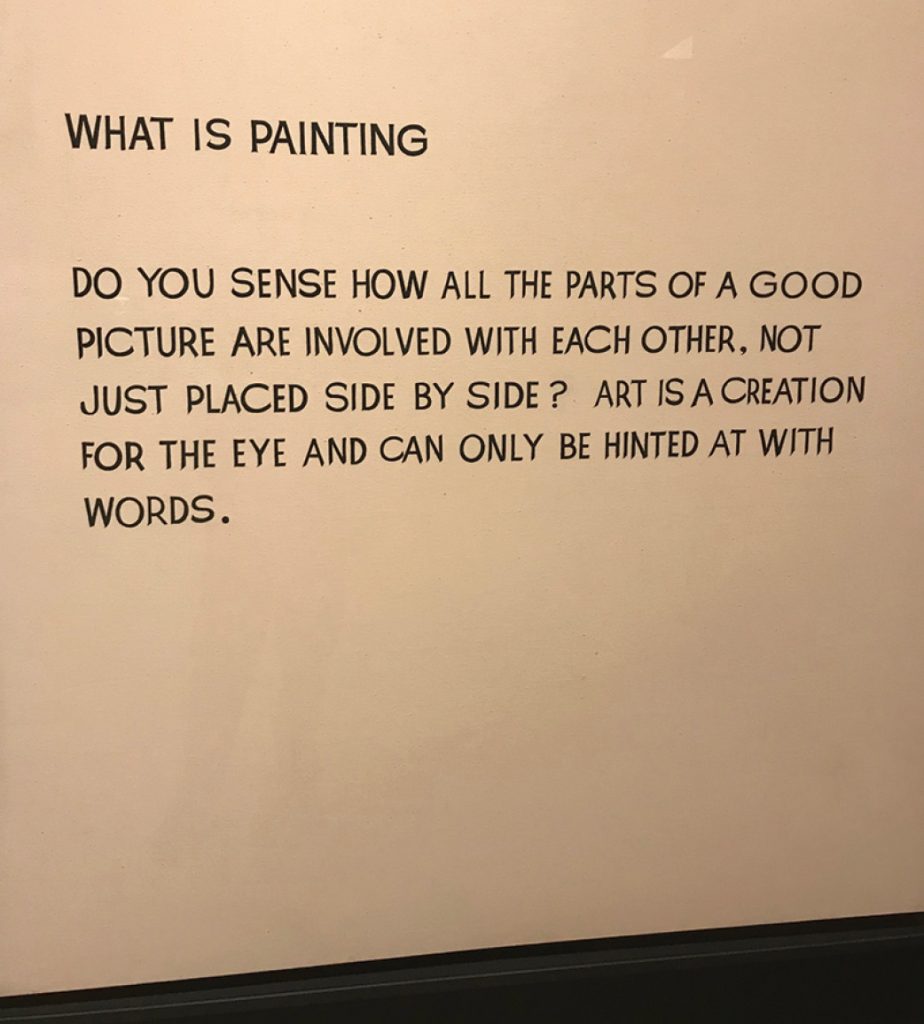

Wherefrom all these memories, the day after visiting a teeming metropolis and an art gallery dedicated to modern art? If, as I think I have heard or read somewhere, Art is intended to make us think, then the following passage written by one John Baldessari, on a framed work titled “What is Painting” was the standout piece of art that captured my thinking equipment. The work, hung in simple wooden frame, about 4’ by 4’, presented on a background color of the family file folder, and written in block letters, black and square, all caps.

This piece is large enough to capture the eye from across the room, in the same way a looming cloud might get your, and make you pay, attention. I wandered over to the work and read it a few times. What it really made me think was how much like sailing, art is, as defined in this way. OR actually the other way around, how much like art, sailing is. Nothing in, on, or around a sailing boat exists in its own universe; a sailing boat is the original holistic creation.

AND yes, much of the boat is a physical thing, hard and impersonal. Aluminum, carbon, various plastics or wood or steel and so on. None of the parts of a boat are just placed side by side, the bits are all inter-related and without one small part of the whole, the performance of the boat is compromised. One can write a narrative OF sailing, the activity, but not of sailing THE boat. I mean not being on a boat or crewing, for only the person helming the boat is actually sailing. The crew is there poised for the next thing to happen, whether it be mooring, docking, kite change, or, more immediately, trimming a sail. The only person sailing is the helmsman. It is he who feels the boat, the sensation of the resolution of all the forces (there are eight) through the pressure on the helm. Too much pressure. The boat is wild, too little, and the boat becomes too docile; she sits upright and the sensuality on the helm vanishes.

It is this aspect of sailing that struck me reading the work of Mr. Baldessari. All the component parts of a boat can be identified by words, much like an artwork: Mast, boom, line, cleat, sail, wheel, and so on. As with art, say painting, words describe the physical: canvas, paintbrush, oil, water, frame, and so on.

Yet much like the hung work, sailing cannot really be described using words. Yes, we say there is pressure, heel, wind, and so on but the sailing itself, that ethereal feel through the helm that IS sailing cannot be described itself. The results can be articulated, but not the sensation. Not for the first time have I thought sailing is like love, another ethereal intangible that, no matter how hard Mr. Hallmark or Lord Byron try, really cannot be articulated using words. Not for nothing have I thought for a while that sailing is my artform.

I should go to the museum more often. ■

Australian born, Joe ‘Coop’ Cooper stayed in the U.S. after the 1980 America’s Cup where he was the boat captain and sailed as Grinder/Sewer-man on Australia. His whole career has focused on sailing, especially the short-handed aspects of it. He lives in Middletown, RI where he coaches, consults and writes on his blog, joecoopersailing.com, when not paying attention to his wife, dog and several, mainly small, boats.