The Solo Non-stop Circumnavigation of the Mighty Sparrow

By Jerome Rand

I had thought for years about what sailing in the Southern Ocean would really be like. Reading about the “Great Singlehanders” that sailed there, south of the Capes and around Antarctica. These were the first seeds planted in my head while I crewed on boats crossing the North and South Atlantic on delivery trips during my mid-20s. The more I read, the more the thought of my own trip kept coming back to me.

I had thought for years about what sailing in the Southern Ocean would really be like. Reading about the “Great Singlehanders” that sailed there, south of the Capes and around Antarctica. These were the first seeds planted in my head while I crewed on boats crossing the North and South Atlantic on delivery trips during my mid-20s. The more I read, the more the thought of my own trip kept coming back to me.

The spark that really got the fire going was finishing the Appalachian Trail in 2012. I figured if I could suffer through that and reach my goal, to feel the way only a hard-earned and far-reaching goal could feel, maybe it was time to go bigger. So, in the late summer following the 133-day hike from Georgia to Maine I put a plan into action and intended to sail non-stop around the word.

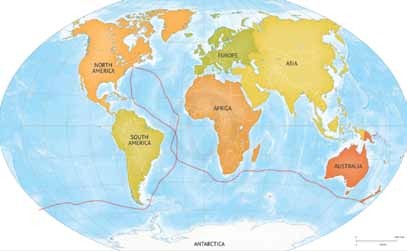

I had no doubt about being unsponsored for the endeavor, as I wanted the trip to be pure and free from any demands other than what I had been dreaming of for so long. I would leave from somewhere north of 40 degrees N latitude, in tribute to the 1968 Golden Globe Race. My only other self-imposed rules would be to sail unassisted, never anchor, and never tie off to a dock or boat. Lastly, I wanted to sail south of all Five Capes; Good Hope, Leeuwin, Tasmania, New Zealand, and Cape Horn. I would succeed in all but one.

To do this I would need a boat, and for that I was going to need money. My plan would take a total of five years from start to finish. I was able to get employment for a three-year run in the Caribbean. After that, I would find the boat and spend a year solo sailing all over the Caribbean and then in the Atlantic. If I could get about 10,000 miles under the keel that should be time enough to sort out the problems and systems for the big adventure. After that, I would haul the boat for the summer to prepare for the trip. Alone, in a basement in Michigan, this all seemed like it would be good fun and not too daunting. I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

Just finding the boat took me across the country to look at more boats than I would like to remember. My budget being small, I was limited to the size and type of boat and soon settled on what would be a very wise choice, the Westsail 32.

The attraction was in the 32’s reputation as a simple, very seaworthy and overbuilt design…that, and I could afford one! It was a match made in heaven. I wasn’t worried about speed; I just wanted to make it around with the best chance of survival. There is also a plethora of information about the boats which I used to strengthen the weak points and simplify the systems.

After a long, hot summer spent in Rockland, Maine, the hurricanes started rolling in one by one. First Irma, then Maria, and finally Jose. It was just about October 1, 2017 when the weather seemed to open up and the Mighty Sparrow was splashed and sailed down to Gloucester, Massachusetts, the chosen start point. With family ties and a history of men risking everything at sea, Gloucester was the perfect choice. It’s also what I consider to be the birthplace of solo ocean sailing, when Alfred Johnson sailed from Gloucester to Liverpool in a 22-foot dory in 1876. Not to mention being the last stop in the United States for Joshua Slocum before setting out on his circumnavigation. I guess I just figured I might as well add a solo non-stop to the books for Gloucester.

After a long, hot summer spent in Rockland, Maine, the hurricanes started rolling in one by one. First Irma, then Maria, and finally Jose. It was just about October 1, 2017 when the weather seemed to open up and the Mighty Sparrow was splashed and sailed down to Gloucester, Massachusetts, the chosen start point. With family ties and a history of men risking everything at sea, Gloucester was the perfect choice. It’s also what I consider to be the birthplace of solo ocean sailing, when Alfred Johnson sailed from Gloucester to Liverpool in a 22-foot dory in 1876. Not to mention being the last stop in the United States for Joshua Slocum before setting out on his circumnavigation. I guess I just figured I might as well add a solo non-stop to the books for Gloucester.

Flags at left in this photo represent the countries where the 5 Great Capes are located (from the top): South Africa, Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand and Chile. Below Old Glory at right are flags of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Dominica, British Virgin Islands and the Falkland Islands. “They saved me from starvation!!!” says the author. © Andy Noel

Within two days that were as much a blur to me then as they are today, I was feeling the goosebumps along my arms as the cannon blasted from Eastern Point and I sailed past the break wall. I was off, and before I knew it, or had even written my first log entry, the coastline had fallen below the horizon and I was alone with the sea and sky.

It is impossible to completely describe what it feels like to begin a trip of that magnitude, but as with all passages the first few hours were spent sorting the last of the gear, double-checking, and thinking that I forgot something very important. But once the sunset came and a hot cup of coffee was in my hand, I had a feeling of overwhelming joy that I was finally there. After months of boat work, years of saving and a decade of dreaming, I was on my way.

The North Atlantic was normal sailing, with the exception of Hurricane Ophelia. Avoiding the storm had me heading south far sooner than I wanted and beating to windward instead of reaching along the northeast trades. For a month I lived at a 20-degree angle, but the Mighty Sparrow held up with only minor breakages along the way to the Equator. I was still eating normal foods right from the fridge, a sundowner each night, and overall great sailing.

Not long after the Cape Verde Islands, the trades eased up and the doldrums had stolen my winds. Nine days, four huge squalls, and some of the most beautiful sunsets I have ever seen took me right into the southeast trades and the South Atlantic. I had suppressed thoughts of the Southern Ocean well until then, but with the latitudes increasing my worries about the weather systems to come grew more and more.

I will never forget seeing the first weather forecast that had just the edge of the Roaring Forties on the map. A huge low-pressure system passing far south gave me a good idea of what I had really gotten myself into. In the end, I figured if it got too much and I just couldn’t handle things I could always head for Cape Town like so many before me have done. So, with a nervous hand we sailed farther south and beyond any horizon I had seen before.

It doesn’t take long to know you are in the Southern Ocean, and within just a few days a near gale had sprung up from the south and along with the wind was the swell. The waves, generally from the southwest, made me feel so small and would never fully disappear until I was in the lee of Cape Horn, many thousands of miles to the east.

It doesn’t take long to know you are in the Southern Ocean, and within just a few days a near gale had sprung up from the south and along with the wind was the swell. The waves, generally from the southwest, made me feel so small and would never fully disappear until I was in the lee of Cape Horn, many thousands of miles to the east.

“Zookeper” is one of very few sailors to complete a solo, non-stop circumnavigation of the world, and the first to do it in a 40-year-old Westsail 32. © Andy Noel

Sailing well south of Good Hope to avoid the countercurrents, the boats in the Volvo Ocean Race 2017-18 peeled out of Cape Town just ahead of a very powerful low that developed over my position. I was lucky to be where I was and not a day or so ahead, since the forecast was for 70-knot winds as the system moved to the east. The Volvo boats got a good push and I caught a lucky break. The swells I saw the morning after the gale had passed were the biggest I would ever see on the trip and in my life. Not dangerous breakers, but moving hills of water that were amazing to behold.

My most serious troubles started in the Indian Ocean, first with the breakage of my hand pump to desalinate water and then with the inventory of my food stores. Rain had been virtually nonexistent so far on the trip and I was very low (10 gallons) on my supply. I had been pumping water for a few days and then the whole thing just popped! I tried about three different ways to fix the problem but with the pressures involved in the pump I found little hope and decided just to focus on collecting rain. The Indian Ocean finally gave me a break with a good squall as I was nearing Australia, but drinking water would be a worry for me for the rest of the trip.

As for food supplies, I thought I had more than enough for 10 months at sea but as the months went by I found that I was eating about two times as much as I had planned. After taking inventory, I had the very real notion that I might not have enough to get me home. Rationing began near my second cape, Leeuwin, and would continue for over two months. I can only guess, but from looking at some of the pictures I probably lost about 45 pounds while I crossed from Australia to Cape Horn.

It was odd being on this new diet. I was always hungry and had trouble staying warm but as far as weight loss, I had no clue what was going on. I never took my layers of thermals off so I couldn’t see what was going on behind the curtain. What was happening was that my body was eating itself, and at a rate I didn’t know was possible.

Once below Australia, I was sailing between 45 and 50 degrees south until the approach to Cape Horn. There I was very hungry, very cold, and trying my best to slowly cross the biggest expanse of ocean on the planet. The thought of heading north was a battle every day at this point, and I balanced my mental state by just taking each day and working my way through. Gales came and went, and I spent a week in fog so unyielding that it shrunk my world down to about 300 feet in all directions. And just to add a little extra gift, everything was wet! The inside of the boat was covered in condensation that sprung to life my only crew: a blanket of mold on almost every surface.

As my position points slowly made their way across the South Pacific chart, it became apparent that I was going to be very close to my own cut-off date of an April 10 rounding of Cape Horn. Slow progress in the Indian Ocean and a week of calm conditions just east of New Zealand had lowered my daily runs and I was now facing a decision I hoped I’d never have to make: press on and hope I make it, or stick to my plan and not attempt to round the Horn after my planned cut-off date.

The weather cooperated, and with a deep breath I made the plunge south of 50 degrees and was hell-bent on rounding the most dangerous of all the Capes. It was a difficult decision to make and I am sure almost everyone that has rounded Cape Horn thinks the same: If I can just make it back to the Atlantic, things will be better there.

The squalls turned to snow and the winds became very inconsistent as I made my approach. It takes about two weeks to get fully around the Horn, and that is a long time to be so vulnerable. The day I passed south of the Horn, a gale sprang up and pushed me along fast on a broad reach. The only problem I was having was timing. I really wanted to see the Cape, but as things turned out I was going to pass in the dead of night and if there ever was a place not to linger, it is Cape Horn.

When I awoke in the morning, I could see a few snowy peaks off in the distance but the truly wonderful sight was the sea: flat calm. For the first time in months, I was in the lee of land! The winds came and went and I found myself on the approach to Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands. Weeks before, I’d figured I would have no chance of making it back to Gloucester without having supplies brought out to the boat. It was either there or in the Caribbean. Why wait?

So, without a chart and in some of the worst squalls I have had to deal with, I made my way about a mile upwind into Port Stanley’s outer bay. I kept wondering if the supply boat would even come out in such weather and when I mentioned that to the crew they just said, “We’re used to it!” The whole offloading took only a minute, and soon I was drifting out of the bay, eating, and stowing as fast as I could. The weather was going from bad to worse and I needed to do only one thing: Get north!

After two more gales in the South Atlantic I was freed from the effects of the Southern Ocean and found the temperature rising so fast I could hardly believe it. Soon enough, I was sailing along in a tee shirt and shorts in the southeast trades once more. I was hoping for a quick trip through the doldrums as the first round took a while and being closer to Brazil usually cuts the chances of encountering large pockets of dead air. I was way off in my thinking. Two hundred and eighty miles in nine days was about the most maddening experience of my life.

After more sail changes than I can count, I found the northeast trades and barely touched the sails until reaching the Caribbean. I had planned to do a sail-by of the BVI and Dominica if the winds allowed and thankfully they did. Both were bittersweet, as I was able to say hello to friends but also saw the devastation of my two favorite islands. The hurricanes hit them both hard and nine months later not even the trees had made a big comeback. It was heartbreaking.

The last leg to Gloucester brought more light winds and a few big thunderstorms, but being back in my home waters I enjoyed stress-free sailing. I was so excited to get home that I had trouble sleeping. After nine months at sea, it was time to make landfall. One last time flat becalmed only 10 miles from Gloucester gave me a little time to clean up the boat and prepare myself for being surrounded by friends and family.

The last leg to Gloucester brought more light winds and a few big thunderstorms, but being back in my home waters I enjoyed stress-free sailing. I was so excited to get home that I had trouble sleeping. After nine months at sea, it was time to make landfall. One last time flat becalmed only 10 miles from Gloucester gave me a little time to clean up the boat and prepare myself for being surrounded by friends and family.

After 271 days at sea and nearly 30,000 miles, Mighty Sparrow approaches the Gloucester break wall. © Andy Noel

As Eastern Point came into view, a few boats started to show up and soon I had my own little armada around me. The cannons blasted and the sails came down. After 271 days and 29,805 miles, I managed to dock the Mighty Sparrow without much trouble and set foot on – thankfully – a floating dock. Had I stepped on hard ground I am sure I would have fallen right over. I will always think of that day as the greatest landfall of my life, a time where I reached my biggest goal, and the time where I told my mother, “I will never do that again!”

Editor’s note: Jerome Rand is the beloved Watersports Director at the Bitter End Yacht Club in Virgin Gorda, BVI. His many friends at BEYC (who affectionately call him “Zookeeper” for his ever-present pith helmet) look forward to welcoming him back. Jerome’s new company is 5thCape Presentations, lectures and consulting, and all of his presentations – at yacht clubs, events, team building, etc. – are tailored to each client’s needs. He’s presenting at the Newport International Boat Show this month and will be on hand for Q&A at the BEYC display. He also hopes to present in the Norwalk area around the time of the Norwalk Boat Show…Mighty Sparrow may be there, too. For more information and to book a presentation, log onto 5thCape.com.

Special thanks to John Glynn, Vice President of Sales & Marketing at Bitter End Yacht Club International, LLC, for connecting us with Jerome.