Last summer we took a trip down the trail of my family’s yachting history, to the fabled hub of New York yachting, City Island. We learned in our research that many of the skilled workers in the shipyards and sail lofts were immigrants. Several were Scots. Much of what has created American yachting tradition came from the British Isles, predictably from England and, surprisingly, a wee bit more from Scotland.

The Clyde

The Solent and the Clyde

In the south of Britain, yachting meant the Solent. In the north, it was the Clyde. England’s Solent is the quirky, tide-wracked body of water bounded by the Southampton mainland to the north, and to the south the Isle of Wight with its central harbor at Cowes. My photos over the years of sailing there feature spectacular wipeouts, ominous tidal rips, plentiful rocks and hectic mark roundings in massive current. In several bouts of racing there, I’ve often felt that racing off Cowes was a game of chutes and ladders, but British royalty and those who followed it found it preferable to any other yachting venue.

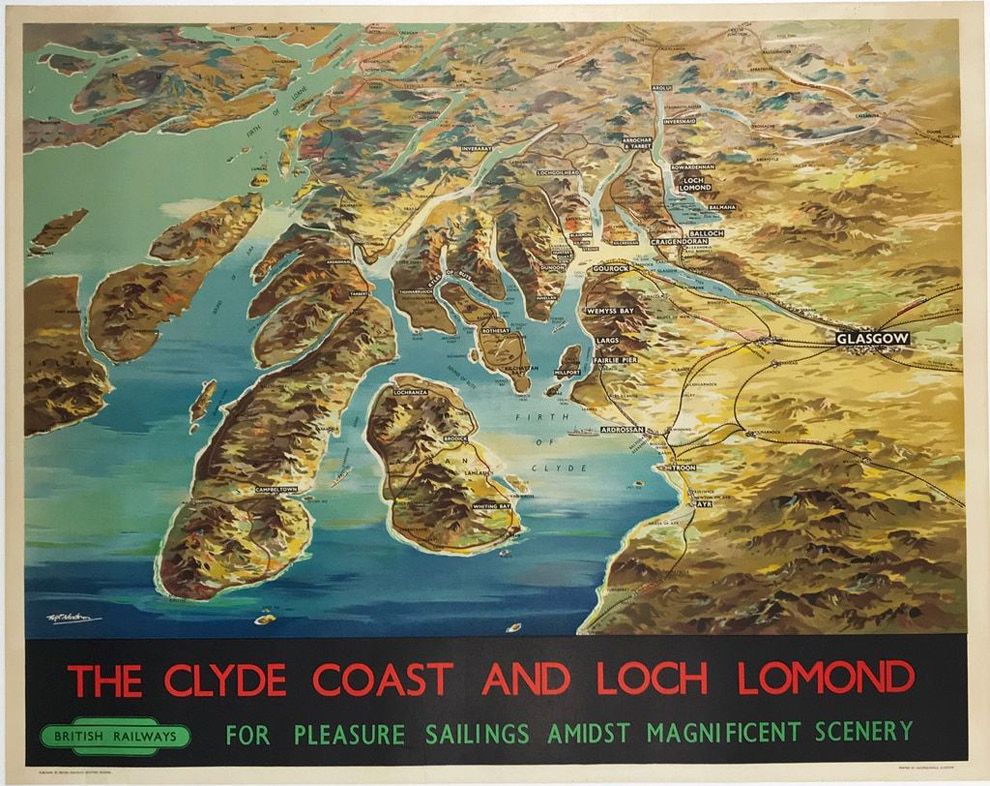

When we talk about Scotland, there is one first seat of Scottish yachting. This is the Firth of Clyde, a fjord-like network of salt water passages, edged by hills, widening as it proceeds south westward to the Irish Sea. Its maritime history is prehistoric. In the Iron Age, dwellers at the water’s edge built stone houses and cairns. Later, the Romans constructed forts while looking out for Norsemen. Eventually, Scottish nobility built their castles round the Firth of Clyde. Based on its strategic location, the points and high ground became the central metropolitan area known as Glasgow. Glaswegians have pride in their northern accent and their yacht clubs, like the Northern YC and the Royal Clyde, were footing challengers for the America’s Cup beginning in the early 1880s.

Glasgow waterfront

The world’s largest liner slips gracefully to the sea, September 27, 1938.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Glasgow was the site of an outbreak of Modernism known as the Scottish Renaissance. This cultural flowering encompassed all aspects of architecture, design, and the decorative arts. The artists who helped establish this movement, Charles Rennie McIntosh and his wife Margaret MacDonald, collaborated on public buildings and residential homes.

With that revival came the designers and developers, first of urban architecture and then uniquely to Glasgow, of massive ocean liners and magnificent yachts. The Firth of Clyde has long been associated with quality boatbuilding and skilled sailors. To most Americans, yacht designers like C.L. Watson, Alfred Mylne, and even William Fife are unknown. Yet while Herreshoff was building 1,521 craft in Rhode Island, both sail and power, from the 1870s to World War II, all of the Clyde designer/builders built more than twice as many during the same period. The best-known Scottish yacht building name, the Fife family, through three generations, built 900 watercraft, almost all sailboats, in that time.

I have never been to Glasgow or the Firth of Clyde. I knew of the dramatic growth of the transatlantic ocean liner scene from my friend Woody Swain. He and his late friend John Maxtone-Graham, author of the definitive history of ocean liners The Only Way to Cross, are the oracles on these giant ships.

I had little knowledge of the yachting scene in Scotland until I met Alisdear Purves, the great, great grandson of the superstars of Gilded Age Scottish sailors, Charlie Barr and his older brother Captain John Barr. While this article focuses on the boats and the builders, the one in next month’s edition will be all about this talented family of Scots from the Clyde. These are the Barrs who came to America in the 1880s and became the most famous boat drivers at the turn of the 20th century.

Shipbuilding, Ocean Liners and the Rise of the Clyde

The ocean liner revolution on the Clyde was a phenomenon comparable perhaps only to the space race. The combination of advanced designs for huge passenger ships, driven by the new Parsons turbine engines and enormous manganese propellors, employed a skilled huge workforce of shipwrights capable of rendering the latest engineering features. Warships were built as well. In fact, the HMS Hood that battled the mighty Bismarck, slid down the ways.

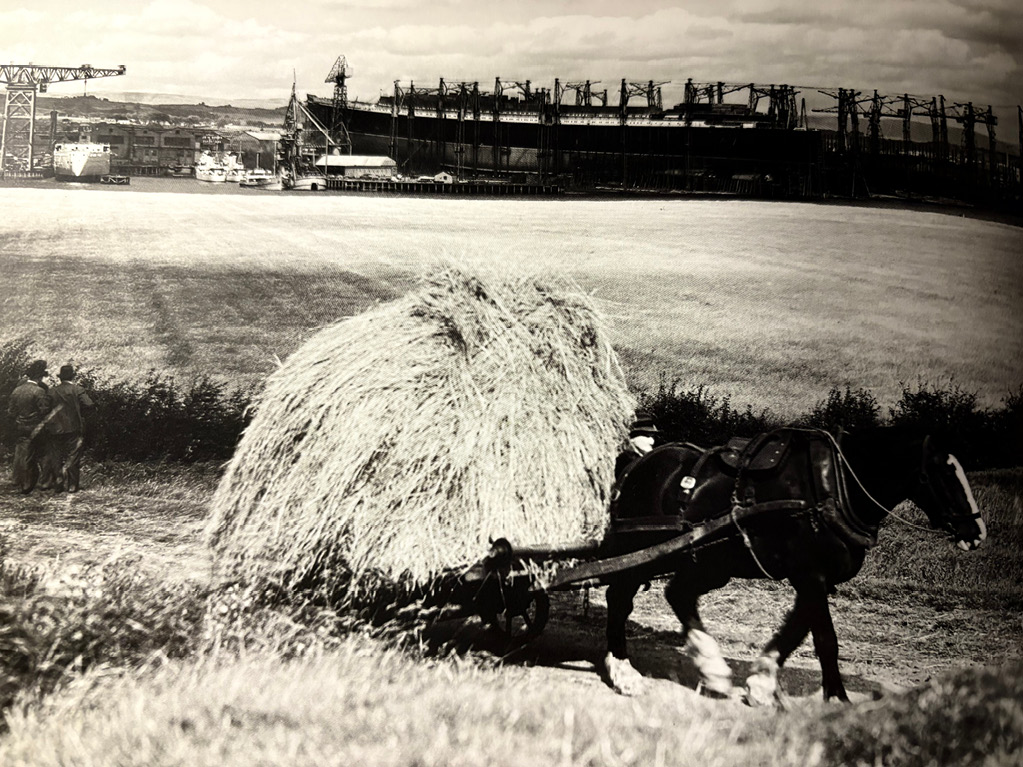

Haymaking by the Clyde with the Queen Mary on the stocks at the John Brown yard, a month before her launch in 1938.

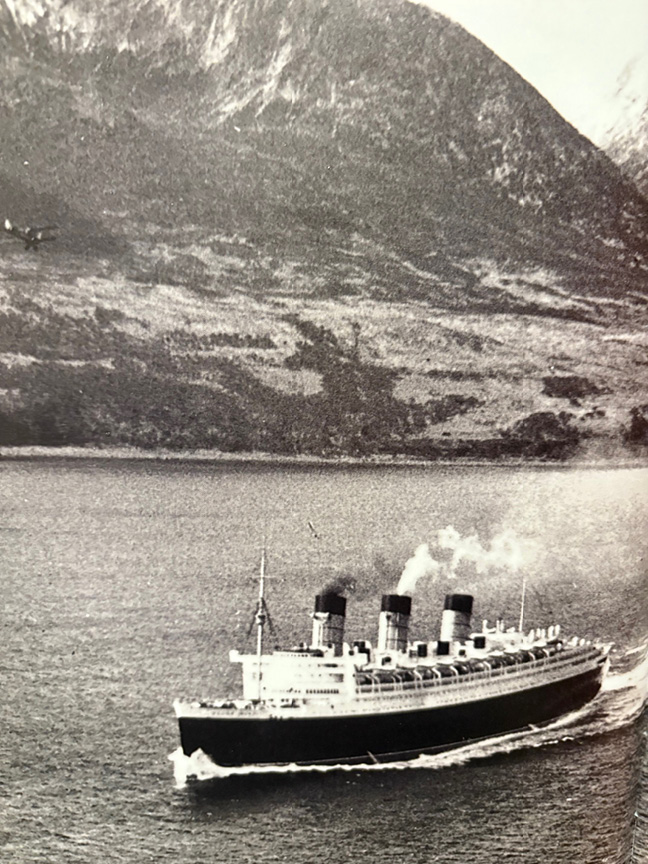

Queen Mary steaming down the Clyde From The Golden Age of Liners, the Getty Collection

A liner hauled for servicing…those props were big!

Ocean liner buffs debate the dates of the Golden Age of Ocean Liners. Our best guess is the two generations from 1880 through the late 1930s. There were fourteen so-called four-stacker ships close to 1,000 feet long built during that time. The Queen Mary, pictured steaming down Clyde, was 1,019 feet long; the Titanic 140 feet shorter. They were the wonders of the maritime world; for their passengers, a floating World’s Fair.

America prospered in the late 19th century on the back of its railroads. Scotland did so on the engineering and construction of the ocean liner. The demand for passenger liners as well as the growth of the Royal Navy fed a demand for maritime manufacturing talent. Glasgow’s position in shipbuilding attracted the best and brightest from both sides of the Atlantic.

An example was Clinton Crane, one of the most prolific American yacht designers of the 20th century (the 6 Metre Lucie, the 12 Metre Gleam). Crane graduated from Harvard in 1894 and headed to Glasgow for his Masters in propulsion systems. It was Glasgow that was providing the new engines and propellor designs for warships and ocean liners. It is instructive that Nat Herreshoff left MIT in 1874 with a degree in propulsion and spent several years with the Corliss Steam Boiler company before joining the family firm in Bristol. New England and Glasgow were on the leading edge of the revolution in maritime design and power.

Three Fifes, a thousand boats

In America, Bristol had Herreshoff. On the Clyde, Fairlee had the Fifes. The company’s address was listed for 150 years as “Scotland, Ayrshire, Fairlee.”

A Fairlee tourist brochure summed up the significance of the Fifes: “The Fife classic yachts are a shining example of the amazing skill and determination of the local people in Ayrshire.”

In his massive book The History and Evolution of Sailing Yachts, Franco Georgetti summarizes the Glasgow yachting scene in 1900:

“Some of the most important British yachts of the turn of the century sailed on those waters reflecting the dark greens of the Scottish coasts… The Clyde certainly saw Lord Dunraven’s Valkyries and Sir Thomas Lipton’s Shamrocks before they crossed the Atlantic and bravely but vainly challenged the Americans of the New York Yacht Club for the America’s Cup.

“And then there were all the yachts built in a yard that was a family firm for four generations from 1791 to the post-Second World War period and was to be a symbol of the Clyde and a legend in world yachting, the Fife yard at Fairlee.

“Anyone with an opportunity to see the Richard Mille Fife Regatta in early June on the Clyde, chilly as it might be, will see iconic turn of the century yachts in action. This event features boats built beginning in the 1890s through the late 1930s with a dizzying variety of rigs.

“Initially Fife built small sailing yachts, to his own design, for the wealthy middle and upper classes of Glasgow…William Fife III was designing up to fifty yachts a year, half of which were built in his own yard, the others in Europe, America and Asia.

“The fame of the Fifes had, in fact, crossed the oceans, and after it had appeared on the Dragon (a Fife boat), a gilded dragon carved in the stringer on the prow was a feature of all their boats from 1889. The symbol distinguished yachts that were to become famous for their beauty if not necessarily their performance.”

A century ago, liners were the way to cross the Atlantic.

There were three William Fifes, I to III. William Fife I, the founder, worked with a sawpit and a blacksmith bench to construct traditional English designs known as cutters. He launched them on a so-called slipway at a sandy beach in a town named Fairlee (located on the water west of Larg on the map).

William Fife II joined the business when he was 18 and built the iconic Stella in 1849. In later years he worked with William III on the early Cup boats of Sir Thomas Lipton, who himself was Glaswegian, an Ulster Scot, having come from Ireland.

By 1902 when Fife II died, the Fife yard had taken over the entire Fairlee shoreline. The yard had every modern boatbuilding innovation, from outdoor lighting for night construction to foundries for all their parts. The Fifes knew, as Herreshoff did, the importance of being fully integrated.

William Fife III did his first designs in 1890 and went on to become one of the most renowned designers of the 20th century. He created scores of elegant offshore boats as well as two of Lipton’s first America’s Cup Challengers, Shamrock in 1899 and Shamrock III in 1903. While Herreshoff was working feverishly at his peak, Fife was booming as well. Fife shared some habits with Nat Herreshoff, and certain aspects of their design philosophy and working style were similar.

Franco Geogetti summarized Fife III’s approach in Sailing Yachts: “He was not a true conservative, as he always sought out new features and his boats rarely resembled one another except for the fact that they were all aesthetically exceptional. Having little faith in the scientific approach (quite different from Herreshoff), he preferred to continue to design yachts on the basis of half models, but the unmistakable elegance of his designs was frequently accompanied by good performance.

“William III’s best known designs came in the time after World War I. In 1922, he was the first designer to produce a 12 Metre yacht to the new formula (International vs Universal), revised in 1921, the Vanity. (This was the rule that set off the boom in Six Metre construction.)

“In 1926, he was probably the first British designer to employ a Bermudian mainsail on the stunning Halloween, designed according to the 15 Meter ratings but in reality a compromise between this type of yacht and an ocean racer.

“Photos of Halloween today show a close to 24-meter yacht, cutter rigged, with all the panache of an AC boat. She lived part of her life as the yawl Cotton Blossom and dominated ocean racing for many years. She was restored to her original lines at the Classic Boatworks in Newport, RI between 1988 and 1991. Following some touch-up in 1994/’95 in France, she was totally redone for shorthanded racing/cruising.”

Halloween returned home to the Clyde in 2008 where the familiar craftsmen at Fairlee Restorations did important structural work on hull and keel. Such is the journey of a famous vintage boat. Today, she’s yours for 1,450,000 Euros. Says the listing: “She’s considered the most beautiful Fife ever built, and is still winning classic regattas whilst at the same time able to make fast passages across the oceans. With her new and intelligent deck layout she is able to be sailed by only two people for short deliveries and can race with six crew.”

The Richard Mille Fife Regatta is the largest gathering of Fife yachts in the world. Courtesy fiferegatta.com

Another one of Fife’s most recognized designs, Altair, personifies the large schooner of the early 20th century. No English sailing calendar exists without this pearl white 130-footer, perfectly restored today. In Georgetti’s words, “Like all the Scotsman’s designs, she is above all beautiful, but also boasts excellent sailing qualities.”

We have had the privilege of sailing on two designs of William Fife III, from his mid- to late career. They are Clio, Invader and Defender, part of a collection of classic vintage wood boats kept in a private foundation in Oyster Bay, New York, adjacent to Oakcliff Sailing.

Held in early June on the Clyde, the Richard Mille Fife Regatta is often a test of hardiness. Courtesy fiferegatta.com

The daysailer, Clio, is pure white and a delightful boat for a couple on an afternoon spin. She is Fife’s 1921 modernized version of the so-called British Cutter. At 45 feet, 9 inches, she looks most like Herreshoff’s NY 30, which is several feet shorter.

Today, we define a cutter as a boat rigged with a single mast and two or more foresails. In English terms, the term cutter came to be used to describe a kind of yacht that was fairly narrow, with a deep draft and rigged with a single mast and a long bowsprit to carry more than one jib. In England, they were often used for their speed to catch smugglers. Freed from being pure working boats they then evolved into recreational sailing craft. The classic cutter shape of the 1870s had a vertical bow, a very narrow hull, a running bowsprit, gunwales low to the water. One can see that style reflected in British America’s Cup challengers like Thistle, the Royal Clyde YC entry in 1887, designed by one of Scotland’s traditionalists, G.L. Watson. Clio came much later, in 1921, but the long bowsprit and low profile are features from the cutter age.

Fife III provided the design of many 8 Metre yachts. The designs were first done in 1928 and then refined for Olympic competition in 1930 and ‘32. The latter Games were in Los Angeles, and the original Fifes made an impression. Invader and Defender have the characteristic Chinese dragon on the bow. They require a crew of six to operate their 46 feet of sleek black and white speed.

Long Loch: The oldest one-design on the Clyde

The Clyde’s oldest one-design is the Long Loch. It is, as the Scots say, a “wee” boat, only 21 feet, with a gaff rig. The Long Loch has a dedicated group of owners determined to keep their 150-year-old boats racing. My friend, who sails one, admits that the ratio of maintenance to sailing time is about 1:1. The Long Loch looks to our eye like Cape Cod’s Wianno Junior ready for hard wind and rough water. About twenty sail in the Firth of Clyde and the Norfolk Broads on the southeast coast.

The Long Loch has a distinction that even native Scots don’t seem to know about. It is the oldest continuously raced one-design class in yachting history, and another piece of the Clyde’s maritime tradition. But to escape fickle Scottish summer weather, owners periodically organize a regatta in the South of France. They are smart, these Scots.

In the next issue, we will feature the top Clyde sailing family, the Barrs. ■

At a wee 21 feet, the Long Loch is the oldest continuously raced one-design class in yachting history.

Not a formally trained historian nevertheless a boat storyteller, collecting and reciting stories for the boating curious, Tom Darling hosts Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.

Sources

The Only Way to Cross, John Maxtone-Graham, 1972

The History and Evolution of Sailing Yachts, Franco Georgetti

Website: Stirling Sailing Foundation (Clio)