By Dr. Paul Jacobs

1990 C-34 #1068

My partner Nancy and I have had the good fortune and great joy to sail our 1990 Catalina 34 Pleiades throughout the splendid and historic cruising grounds of New England. She is based out of Wickford, Rhode Island, only five miles from our regular home, but from early May through late November she effectively becomes our floating home.

My partner Nancy and I have had the good fortune and great joy to sail our 1990 Catalina 34 Pleiades throughout the splendid and historic cruising grounds of New England. She is based out of Wickford, Rhode Island, only five miles from our regular home, but from early May through late November she effectively becomes our floating home.

This photograph shows Nancy, myself, and our beloved C-34 on the East Passage of Narragansett Bay. © Daniela Clark/PhotoBoat.com

Others spend millions for waterfront property in the Ocean State; each with a specific view. However, Pleiades affords us “water surround” property with spectacular views that change every time we set sail!

Last summer we sailed Pleiades to Third Beach, Cuttyhunk, Mattapoisett, Red Brook, and one of our favorite cruising spots: Kettle Cove on Naushon Island. While many other New England harbors are listed in various cruising guides, Kettle Cove is not. In a way, that is fortuitous, since it is rarely crowded, and on some summer days when Block Island is literally “wall-to-wall” with powerboats and sailboats, we have actually found ourselves completely alone on the hook at Kettle Cove. The good news about this “off the beaten track” location is: (1) a beautiful, long sandy bight protected from winds ranging from SE around to W, (2) very clean water that is great for swimming, (3) a tiny freshwater stream running down to the bay, (4) the complete absence of houses, stores, roads, cars, and streetlights, so that on a clear night one has a fabulous view of the dark night sky, and finally (5) a sand bottom out to 20 feet depth which provides outstanding holding. The only negative is that if the prevailing SW wind is strong, ocean swells can refract around the west end of Naushon Island, through Robinson’s Hole, and into Kettle Cove. This happened to us a few years ago, and the night was spent listening to pots and pans clattering, and plates and glasses sliding side to side in their galley storage compartments.

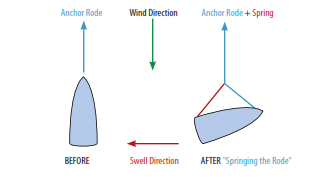

Surely, at one time or another all sailors have confronted this situation. The wind is from one direction (e.g. SW) but the swells are from another direction (e.g. NW). In our case Pleiades aligned herself primarily into the wind, but the swells were arriving from very nearly perpendicular to her starboard beam. At this point you will either: (A) suffer a brutal night with much obnoxious rolling, or (B) you may choose to put out a second anchor, or (C) you may finally decide in desperation to move to another harbor that is better protected from the prevailing wind and swells. Or (D)…and this is of course the point of this note…there is another wonderful alternative. You may choose to simply “Spring the Rode.” I learned about this technique from a book describing some of the Royal Navy ships-of-the-line in the early 1700s. One of their standard techniques in cross-swells was indeed to “Spring the Rode.”

Springing the rode is so simple that the first time we employed this historic method, Nancy and I looked at each other afterwards and wondered why we had never thought of doing that before! Let me illustrate schematically with the situation we encountered at Kettle Cove; the wind was SW at about 12 – 15 knots, there were 1 to 1.5-foot swells from the NW, the bow was pointed SW, the anchor chain and rode had been paid to 7:1 scope, (i.e. seven times the sum of the 15 feet water depth plus the approximate 4 foot height of the C-34 bow roller above the water), or about 135 feet. The anchor was holding beautifully, but unfortunately the hull was rolling back and forth in a nasty manner, and Nancy and Paul were not at all happy sailors. It was time to “Spring the Rode.”

Step 1. Select a strong line longer than your sailboat. A spare halyard or jib sheet is perfect.

Step 2. Tie that line snugly to your anchor rode just forward of the bow, with a running hitch.

Step 3. On the side opposite from the waves, lead the line aft, and outboard of everything.

Step 4. Using a fairlead to avoid overrides, run the line to a primary winch, and snug it taut.

Step 5. Gradually ease out on the anchor rode, until the bow points into the swells.

Step 6. If the wind shifts, make fine adjustments to the ship’s heading, using the primary winch.

Step 7. When the rolling motion is replaced by modest pitching…SMILE!

Not only is this much simpler to accomplish in the dark than setting a second anchor, but if the wind or swells should happen to change direction during the wee hours of the night, and you are awoken by more nasty rolling, it is very easy to let out a few feet, or grind in a few feet of the spring line simply using the primary winch, until the rolling has again been greatly reduced or totally eliminated. After you have “Sprung the Rode” even once, you will never again put up with extreme rolling at anchor.

Fair winds, following seas, and smooth anchoring.

Dr. Paul Jacobs and his partner Nancy Kaull are frequent WindCheck contributors. Excerpts from their highly recommended book, Voyages: Stories of ten Sunsail owner cruises, can be found at http://www.windcheckmagazine.com/voyages.