The Song of the Solo Sailor

By Tom Darling, Conversations with Classic Boats

Clay Burkhalter sailed Acadia to a 13th place finish in the 2007 Mini Transat.

What is it about the solo sailor that so captures the imagination of the ranks of normal sailors? Slocum. Chichester. Knox-Johnston. All have this mystique of man against the elements, alone. In curating Mystic Seaport Museum’s current exhibit, “Story Boats: The Tales They Tell,” Christina Brophy, Senior VP of Curatorial Affairs, ran her own “Maritime Idol” competition. Of the eighteen boats and sailors selected and portrayed, at least three were pure solo artists.

We were able to interview all three, see their pictorial archives, and come to appreciate their sea lessons learned. This article is presented mostly in their own words. Here they are:

Clay Burkhalter, Stonington, CT: Acadia, J/Boats 21, Rod Johnstone designer

Steve Callahan, Lamoine, ME: Avon life raft, no name, no known designer

Dwight Collins, Darien, CT: Tango, pedal-powered vessel, Bruce Kirby designer

We started with Clay because we know him from sailing in his home waters of Fishers Island Sound and dining at his Stonington eatery, the Dog Watch Café. In 2005, Clay got the urge into do the 2007 Mini Transat. This is a singlehanded race with a development-style boat of roughly 21 feet. Today’s Mini 6.50s have foils; then, enormous sprit-launched chutes balanced by water ballast. Clay had the just the designer for the task: his uncle Rod Johnstone.

I’ve seen Clay in many different boats, big and small. He’s a big guy, so I don’t know what he was thinking when he was working with Acadia because she’s a small boat. I talked with Clay on Zoom from his den in Connecticut. I refer to myself in the exchange as TD, Clay as Clay.

TD: Take it from the top, Clay.

Clay: I had never really paid attention to the 6.5 Metre class, but became interested through a French friend who was doing the 2005 Mini Transat on one of these 21-footers. The boats are three meters wide, more or less, and they have a draft of about six feet.

The Mini Transat – meaning transatlantic – is mostly a European event that happens every two years, in odd years. The first running was in 1977. For many years it started in France. You stopped in the Canary Island for maybe ten days and then continued on to the Caribbean. There was very little qualification in the way of events or preparation…you pretty much showed up at the starting line in a 21-foot boat.

Acadia on the hard in Lorient, France before the start

As the years went by, they became more stringent on the qualification. We had to do a 1000-mile solo event. For me, they approved a course that went from Beaufort, North Carolina down around Grand Bahama and finished in Charleston. Then you had to do up to 1,500 miles in pre-race sailing. During the year in France, they have seven or eight qualifying races of various lengths. Once you did that, you were able to enter the race.

TD: How did that work?

Clay: The year I did the race, we had 89 boats and I think 81 of them got to the finish in northeast Brazil. The French are the big offshore shorthanded sailors. Everybody follows it – you could be talking to a farmer in the middle of the country, and he’d know all the big sailors and how they are doing. A lot of the French sailors and some of the British, Spanish and Italian sailors would get pretty significant sponsorship from banks, insurance companies or food companies, and they developed fancy carbon fiber boats which were called the Prototype division. They had another division called Series – they looked the same, pretty much all based on proven French designs. In 2007, 45 of the boats were Series boats and about 40 were Prototypes.

TD: How was Acadia designed?

Clay: I went to my uncle Rod Johnstone, the designer of J Boats whom I’d been sailing with since I was 5 years old. I said, “Rod, would you design me one of these boats?” And I’m sure he said, “What the hell is it?” So we looked online and spent five months going back and forth between different designs.

It’s only 21 feet but it’s a big 21-footer, very fat in the back. Minis have an incredible amount of sail. On my boat, the spinnaker pole stuck out 10 feet in front of the boat. I spent almost 12 months in a shed at Dodson’s Boatyard in Stonington. Rodney would come down almost every day, and I would have more local people show up to help. I was like a tourist attraction. At the launching on a rainy day, about 120 people showed up.

TD: How was the trial run?

Clay: I took off on that thing from Beaufort heading for Grand Bahama. I got out in the Gulf Stream – the first night on this boat – and the wind was against the Gulf Stream. I put her on autopilot and went below in the bunk thinking, “Oh my God, what have you gotten yourself into?” I thought about all the people who helped me and said, “You cannot just call it quits.”

TD: How did the race work out? I heard you ripped up some spinnakers…

Clay: The most intimidating experience was when the trade winds kicked in south of the Canaries the first night. It was daytime and we were surfing. It got a little scary because we were going really fast and the waves were getting big. And I had the biggest spinnaker on, huge pole, full main and the boat was just flying. Then it got dark, and it got windier and windier…

Clay finished 13th out of 82 boats that got to Brazil from France via Madeira.

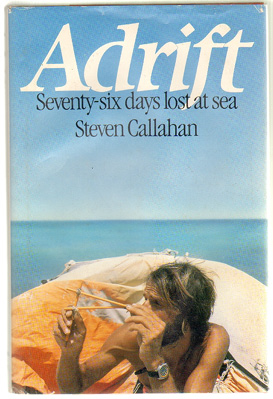

We heard from our second soloist from his home in Lamoine, Maine, near Bar Harbor. Steve Callahan published his New York Times bestseller Adrift, his account of 76 days in a 6-man Avon life raft, following the collision of his Transat boat with an unidentified swimming object in 1982.

TD: Steve, thanks for participating. Please share your story.

Steve: I’ve had the pleasure of messing around at sea and messing about in boat for over half a century, and I’ve done a lot of things within that field: Design, teaching design, building boats, deliveries, offshore, races. Most people want to talk to me because I was dumb enough to lose a boat in the middle of the night in the middle of the Atlantic and spend two and a half months learning to live like an aquatic caveman.

TD: Like Clay Burkhalter, you had a home-built vessel…

Steve Callahan’s Adrift became a New York Times bestseller.

Steve: I built Napoleon Solo, which was 21 feet. She wasn’t really a racing boat but there was a race called the Mini Transat, which is now a very big, popular race. I always was drawn to the shorthanded offshore racing scene, and the boats were interesting for me as someone interested in design.

TD: Between the Bay of Biscay and all the other obstacles, this Mini Transat sounds treacherous.

Steve: It was stormy, stormy, stormy and the Bay of Biscay is pretty notorious, and I had some damage so I dropped out. I figured I was just gonna cruise. I went out to Madeira and down to the Canaries where I spent a couple months.

TD : So you set out to do some trade winds sailing…

Steve: I guess I was about eight days into the passage. And then, Bam! This big crash in the side of the boat and water came thundering in! I thought the boat was going straight down and there was a part of me that was amused. I had a movie camera mounted on the stern of the boat, and when I got up on deck it was taking really dramatic footage, which I thought was amusing. I think it was probably an accidental collision with a whale…

TD: How did you get from the boat to the raft?

Steve: You know, I don’t know…no training. So much of the outdoor experience is dealing with problems. You’re in an isolated environment with limited resources and you become pretty good at that. I had a six-person life raft. And I got it loose and of course its label said, “Toss overboard before inflation.” Fortunately for me, overboard was kind of on board at the time. I had these waves washing over the entire boat.

TD: What did you take?

Steve: I got a piece of cushion, a sleeping bag, and my ditch bag. I really like raw materials that can serve multiple purposes: lot of lot of line, and knives…you know, basic tools.

TD: What time of year was it?

Steve: February.

TD: So it was pretty cool?

Steve: It was cool in the Canaries.

TD: What was the first night like in the raft?

Steve: Oh, horrible. Absolutely horrible: freezing cold and very depressing. I’d read all the ocean survival literature that was available, so I knew it was possible to survive for a long period of time at sea.

TD: Your best selling book Adrift was only possible because of your note taking during the ordeal…

Steve: I kept a log that I brought in my ditch kit. It was important for me to maintain a routine, if you will, on a number of levels.

TD: This was 40 years ago; you talk as if it was yesterday.

Dwight prepares Tango for the very first pedal-powered transatlantic crossing.

Steve: Well, it’s an odd thing. We have things that happen to us that seem to never die and take up a much bigger chunk of our lives than we ever imagined.

Steve was picked up after 76 days at sea. The nearest land was Guadalupe.

Last but by no means least, Dwight Collins, who set a record for human powered craft way back in the early 1990s with an eccentric looking boat designed by the late Bruce Kirby, who passed away in 2021, thirty years after Dwight’s quest to build Tango started.

TD: I just finished talking to Steve Callahan. What I discovered is that there’s a sort of common thread with all of you. It involves a single person taking on a solo challenge. Clay and Steve did their voyages a long time ago, yet they remember every minute detail of the experience Is that the same for you, Dwight?

DC: This was quite an endeavor. I’d just gotten married, and I told my wife about this this idea of pedaling a boat across the Atlantic. She said, “This is a great idea. You really need to do this. It was one of those childhood dreams. I always wanted to row across the Atlantic. I started reading about pedal power and how much more efficient it was than rowing. I thought, “Wow! It would be really cool to have a pedal powered boat that’s fully enclosed, self-righting and completely safe go across the Atlantic Ocean.”

TD: Tango was 24 foot long and 4 feet wide…a big orange Laser with a top. Built with high tech materials by Eric Goetz in Bristol, RI, she was a single purpose vessel optimized to cross from Newfoundland to Plymouth, England as fast as possible. How did you get involved with Bruce Kirby?

DC: Bruce was a member of the Noroton Yacht Club. I grew up sailing there and became a member later on. I called him up to tell him about this idea and see what he thought. He called it the “For Real” project because he was having a hard time believing I really wanted to do this. Later, I found out from his wife Margo that he actually thought I was crazy, but then it was interesting because he realized I really wanted to do it.

TD: Tango is more than a design. It’s a lot of engineering, drivetrain, propeller…

DC: Bruce introduced me to Dave Hubbard, the designer of many racing catamarans. Dave found someone who was working on a pedal-powered helicopter. All the work he had done applied directly to what I was trying to do.

TD: How did you decide whether to go alone, or have a Tango built for two?

DC: I wasn’t sure that I would be able to get sponsorship. I mitigated the impact of the risk of it not happening. I mean, Lindbergh could have taken his wife…but it was deeply personal for me. Callahan had no choice, but for me it was my choice: Go solo.

Dwight Collins pedaled Tango from Newfoundland to England, a passage of nearly 2,000 miles, in 41 days.

TD: It always seems that the solo sailor has that “Aha! moment…

DC: For me, the whole thing came down to an 11-minute period in the middle of the ocean, where the weather had been bad most of the time. All of a sudden the weather turned, the sun was out and the waves were just slow, slow rolling waves. I said, “You know what? I’m just gonna stop, unclip and go outside and look around because I’m never going to be here again.” I sat there and looked around and it was just ocean and sky, and it just fed my soul. It really did. It made it all worthwhile.

TD: What did it feel like when you got to England? Who saw you first?

DC: Well, that’s a great story. My first sight of land was the Scilly Islands. I heard the sound of an engine. It was a family off the coast…a husband and wife and two children in lifejackets. They came putting over to the boat. With a fairly heavy British accent, he asked, “Excuse me. What kind of boat is that? Where are you from?” I said, “I came from St Johns, Newfoundland. He said, “Oh. Thank you very much” and they left. Fifteen minutes later, they came back and he said, “I’m sorry, but I just want you to know what you did is amazing!”

Tango came back on a freighter and resided for a time at The Maritime Aquarium at Norwalk. The orange craft subsequently sat in Dwight’s yard until Bruce Kirby, who had donated Laser #0 to Mystic Seaport Museum, suggested Tango go there too. She is now perched on the lawn in front of the Thompson Exhibition Building,as part of the Museum’s Story Boats: The Tales They Tell exhibit, running now through August 14. ■

Scan here to listen to the author’s Conversations with Classic Boats podcast.

Tom Darling is the host of Conversations with Classic Boats, “the podcast that talks to boats.” Tune in via Apple Podcast, Google Podcast or Spotify, or online at conversationswithclassicboats.com.