Part I: Carleton Mitchell: John Muir of the Caribbean, Bermuda Race Legend

By Tom Darling

This is the tale of two boats: one famous, one not. For these two classic cousins, it was the best of times, it was the worst of times. That is how the career of classic boats can be. One boat, the rock star design of the 1950s, was the winner of three successive Bermuda Races, a feat never done before or after. The other, the country mouse, content to ply the waters of southern New England, has been fortunate to have passionate and careful owners who in fact collected plenty of silver in classic series racing.

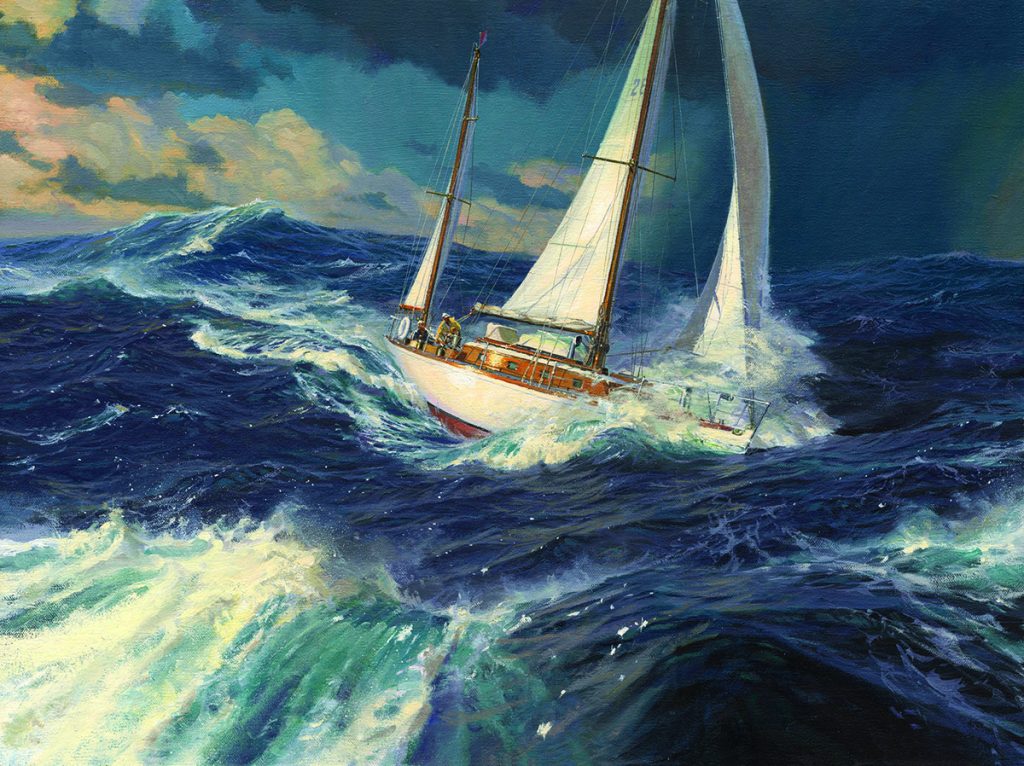

“Finisterre, 1956” – This dramatic painting by Russ Kramer depicts author, photographer and adventurer Carleton Mitchell’s yacht on her way to the first of three consecutive victories in the Newport Bermuda Race. To see more of Russ’ work, visit russkramer.com.

The boats are Finisterre and Fidelio, Sparkman & Stephens designs of the 1950s, and with a shape that influenced American racing boats for a generation, bridging the long, deep boats of the International Rule and the new wave fin keel and spade rudder boats that came in the early 1970s. In their day, they were radical. Even today, their innovations in design and rigging command our attention. They are the Centerboard Cousins (Keelboat Killers), and this is their story.

One of the boats is famous, even legendary – Finisterre. Who doesn’t know of the little 38-foot Olin Stephens boat that slew the traditional dragons of mid-1950s yacht racing in the Dash to the Onion Patch, the Newport Bermuda Race? She won not once, not twice, but three times in a row starting in 1956. The yachting elite must have seen her bobbing in Hamilton Harbor until they couldn’t stand it anymore.

And there was an anonymous twin, two years younger, technically a cousin that most people in my modern sailing world never saw until 2008, when her modern owner fell in love, restored and campaigned her for over ten years. This pair had one set of Olin Stephens plans in common. In the Photos section of our Conversations with Classic Boats website, Episode 5, you can see them in detail (conversationswithclassicboats.com).

Their crews both sailed the same design, tens of thousands of miles in virtually the same wooden yawls. They were built two years apart and in boat yards 4,000 miles apart, but otherwise they are identical. These twins are S & S 39s; the Bermuda Race killer and the master of the CRF rule respectively, with dozens of trips to the podium for inshore keelboat wins. They have had very different career paths. Technically, they are not twins – they would have had to be born and launched together. So they are cousins, with five others known sisterships built to the Finisterre design.

The two cousins remind me of a show from the Golden Age of TV. For me, a Boomer of the TV Age, they are the characters in the Patty Duke Show. In that comedy, Patty played two versions of herself at once: the Park Avenue dandy and her identical cousin, the country mouse. That’s Finisterre and Fidelio. Finisterre, the offshore rock star and blue water cruiser; Fidelio, the quiet one turning heads in coastal New England. From the 1950s to today, these are two extraordinary boats leading different lives.

This story is inspired by someone I met once in my life, but who is legendary for his enthusiasm and joie de vivre as a pioneer in the post-World War II boating world, in addition to being a world-beating offshore racer. This individual is Carleton Mitchell, the pathfinder of blue water cruising in the second half of the 20th century and the owner and captain of Finisterre, one of the most influential designs of the 20th century. Twenty-twenty was the 110th anniversary of Carleton’s birth and the 13th of his passing at 96, exiting as he came, an old salt living on the edge of Biscayne Bay.

Finisterre and “Mitch”: Pathfinders to the West Indies

Finisterre was the third child of a charismatic sailor, Carleton Mitchell, nicknamed “Mitch,” an original, the first with a robust media personality, an influencer, and an ambassador of the seas. Let’s set the nautical scene in the West Indies after WW II. For more than 200 years, following the American Revolution and the roiling naval wars of Britain and France, the Caribbean – then referred to as “the West Indies,” slumbered with its plantation history and isolated tourism. Cruising in sailboats in a modern sense did not exist. Few sailors had the chance to take a taste of the region’s trade winds and aqua waters. Sailing visitors were mainly large yachts, epitomized by the somewhat cheesy sailing equivalent of the modern cruise ship, the windjammer. The scene was Pirates of the Caribbean – bad rum drinks with little umbrellas, not exhilarating experiences in pristine sailing conditions.

One individual really changed that: Carleton Mitchell. The son of a doctor from New Orleans who had no interest in boats, Carleton went sailing with an uncle in New Orleans. He came back and told his mother, “I want to sail, and I want to write about it.”

Mitch dropped out of college in Ohio in the late 1920s, at the beginning of the Great Depression. There followed a series of jobs including working in a Minnesota lumber camp and eventually selling women’s underwear in Macy’s in Manhattan. The drifting ended when he joined a friend on a voyage from Norfolk to Nassau in the Bahamas. John Rousmaniere, the author and a longtime friend of Mitchell, said in a Soundings article in 2007, “The boat almost sank on the way. It was a dreadful trip. He had the wits scared out of him, but he loved it.”

When he came back from Nassau, where his own personal photos always lovingly depicted, whether it be with one of his own boats or a windy Star regatta, he tried to write travel stories with no luck. Someone said, “You need pictures.” He scraped together enough to buy a camera and darkroom equipment and set it up in his shoebox Manhattan apartment. Today, Carleton would be a rad YouTuber…or collecting cruising cash on Patreon.

In 1945, after the war where he served in the U.S. Navy as a photography instructor, the amateur photographer who had spent the Depression bouncing around the marine world needed a mission. He got married and he got himself an old boat. He was in Annapolis, home of the Navy. The name of the old boat was Carib and her cruising ground started in Trinidad and extended north to the Bahamas. For those pioneering years into the early 1950s, this Alden ex-schooner formerly called Malabar rerigged as a ketch was his ride. Then and in its successor, a 58-foot Rhodes design called Caribee, Carleton Mitchell transformed himself into the Pied Piper for Caribbean sailing.

This Caribbean-American Odysseus crisscrossed what he called the West Indies, what we still call the Windwards, the Leewards, the BVI, the Bahamas. He travelled light aboard his boats – no scuba tanks, no paddleboards, and no windsurfers like the floating motor palaces that traverse the Caribbean winters these days. He had clothes, a tripod and a camera, a wife and an eye for the picaresque. He took not just postcard shots, but the photos of a sailing anthropologist, the people and their boats and their weather, from booming cumulus clouds to the endless horizons, the Green Flash. He was not a solo sailor, he had his friends, and then his wife, and more friends. He was a highly social sailor.

Carleton was an underappreciated photographer. He had worked during the war in the Naval photo archives. He could pick a nautical image out of a lineup and it would be the right one. Tens of thousands of pictures came from that imagination from 1945 through to the 21st century. For more than 50 years, the yachting world saw his vision of nautical in Yachting, in Sports Illustrated and in his series of books incubated by his postwar exploration of what we still called the West Indies.

Through both his writing and pictures, I grew up on his America’s Cup coverage in Sports Illustrated, in his seven books and his racing success. To me, he was a blue water sailing celebrity, really the first in the postwar era. When you look at his photos, you realize he must have taken inspiration from the WPA photographers on the time, from the 20s – Steichen, from the 30s – Walker Evans, Edward Weston, Ansel Adams. He had been in New York when it was a hotbed of photographic ferment before the war. In the jumbled inventory of 20,250 photos given to Mystic Seaport Museum, there are the tourist shots – no people, just scenery, those placid waters, those billowing tradewind clouds, the native boatyards and watercraft, and the Antillean people themselves, every island a mix from the past of colonialism and migration and native culture.

In the aforementioned October 2007 article following Mitchell’s passing in July of that year, his friend John Rousmaniere wrote, “If you were to add up the ten most important people in sailing over the last 100 years, he’d be in it. And not just because he won three Bermuda Races. He was really a three-sport star: All-star sailor, writer and photographer. He was the greatest yachting writer of his time.”

The first book, Islands to Windward, exposed the world to the potential of the Caribbean charter business as it evolved from cruise ship style tourista in windjammers to self-catering adventure cruising amid islands that had seen very few yachting tourists. Each of his pictures at sea is of his boat or from his boat. Carib was the first, the former Malabar X, one of the John Alden schooner-style yawls that could fly on a reach when flying all five sails. Carib was followed by Caribee, a 58-foot Rhodes design. Between them, they were the Where’s Waldo of almost every Caribbean yachting scene known to sailors.

Although she’s less well known than her celebrated cousin, Fidelio has nonetheless garnered her share of silver on the classic yacht racing circuit. © Billy Black/billyblack.com

When Carleton died in 2007 at 96, his family may have looked at what he had accumulated: almost 20,000 so called “safety negatives” and silver prints – the same as made by an Ansel Adams or an Edward Weston. Their decision was to bequeath the portfolio to Mystic Seaport Museum along with reams of notebooks and the work for the series of books that Mitchell published beginning in 1947 with Islands to Windward. John Urban, the Museum’s Development Director, described to me what his own impression of looking at that massive collection for the first time. “I took the deep dive in the collection,” he reported. “Too much!!!” Exactly my impression when I pored through the photos and glanced at his cruising guides, a genre that he formed along with originals like Fessenden Blanchard and his Cruising Guide to the New England Coast.

Viewing the photo archive, I suddenly recognized that I was looking at another pioneer of the outdoor life – the John Muir of boating, yachting and cruising. If I were reading Muir on the Maine woods, I would be reading Mitchell on Martinique or Trinidad or the Abacos: Two parts travel guide, one part outdoor philosophy. A rugged individualist like Muir, Mitch defined the genre, the style and the medium for years to come.

Next time in Part II: Finisterre and her sistership turn the sailing world of the 1950s upside down with Olin Stephens’ radical new approach to ocean racing design. ■

Tom Darling organizes Team Dolphin for its annual Opera House Cup sail, and sails Alerions in Nantucket Harbor. You’ll find his Conversations with Classic Boats podcast at

conversationswithclassicboats.com.